- | 8:00 am

Meet the woman who’s making climate change easier to see

Alison Smart started her career in the arts. She quickly realized that her skill set was all too applicable to the climate crisis.

Alison Smart is Executive Director of Probable Futures, a climate literacy platform using innovative climate change visualization to help people see the impacts of climate change and build support for urgent action. She spoke to Doreen Lorenzo for Designing Women, a series of interviews with brilliant women in the design industry.

Fast Company: How did you get here? Was it a straight shot, or did you take a curvy road to this position?

Alison Smart: Since college, I have worked in different types of nonprofit leadership roles. I had grown up being very active in the arts, so when I went to the University of Miami for music and theater, I quickly got involved in helping run the University theater. I worked at a ballet company right out of college and then went to the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida. From there, I moved up north to work at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, which is an institution that brings together science, culture, art, conservation, and ocean ecology through historical storytelling. I spent almost nine years at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in fundraising and communications, learning how to be an interpreter, translator, and storyteller.

Over my time at the museum, I transitioned from the arts to history and then to climate science. The more I learned about environmental issues, the more urgent climate change became in my mind. I put out that I was interested in working with environmental organizations and then a recruiter got in touch with me to work at Woodwell Climate Research Center as Vice President for Strategy & Advancement. The organization recognized that climate scientists needed help communicating their work to general audiences and that it would take people from outside of that community to help translate it in that way.

How did you transition from the Woodwell Climate Research Center to Probable Futures?

It happened pretty organically, actually. The origins of Probable Futures began with its founder, Spencer Glendon. In his prior role as Director of Investment Research at Wellington Management, one of the world’s largest asset management firms, he was working to build a bridge between climate science and finance. When Spencer started looking for potential collaborators, Woodwell was a perfect fit considering the organization was founded to enable climate science to inform real world decision-making. Its purpose was to answer other people’s questions, and produce science that was useful.

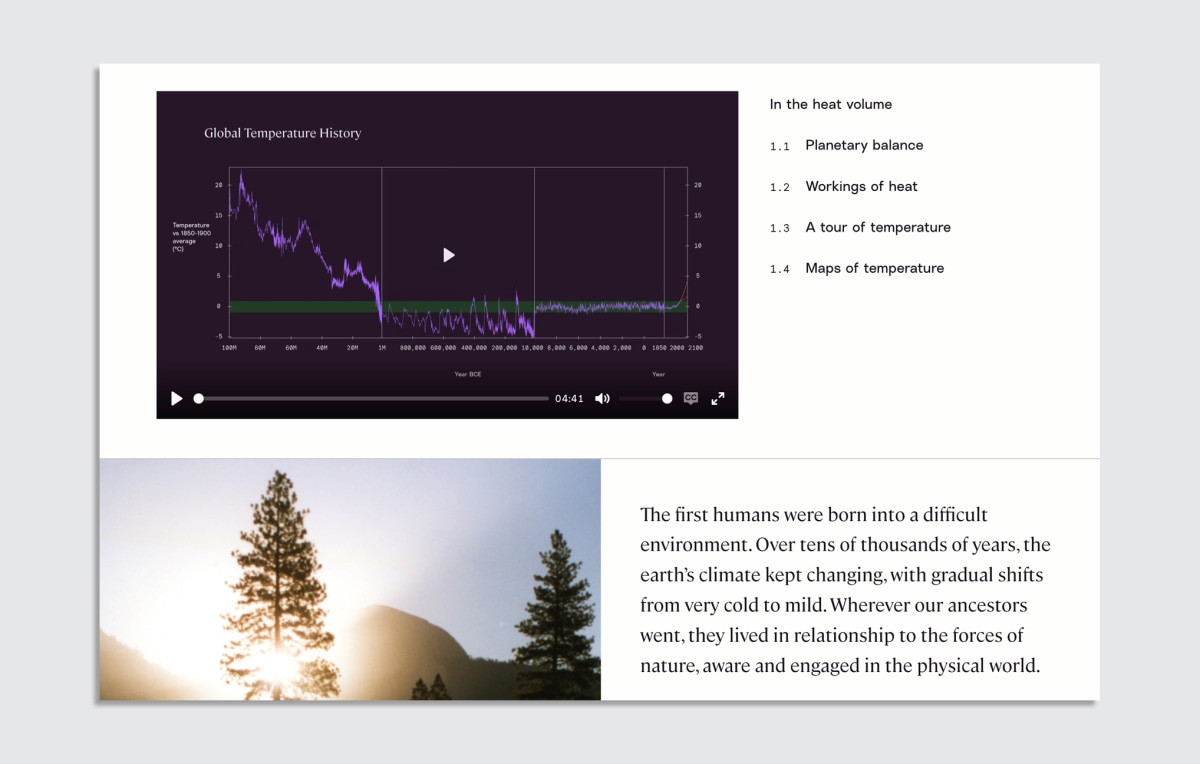

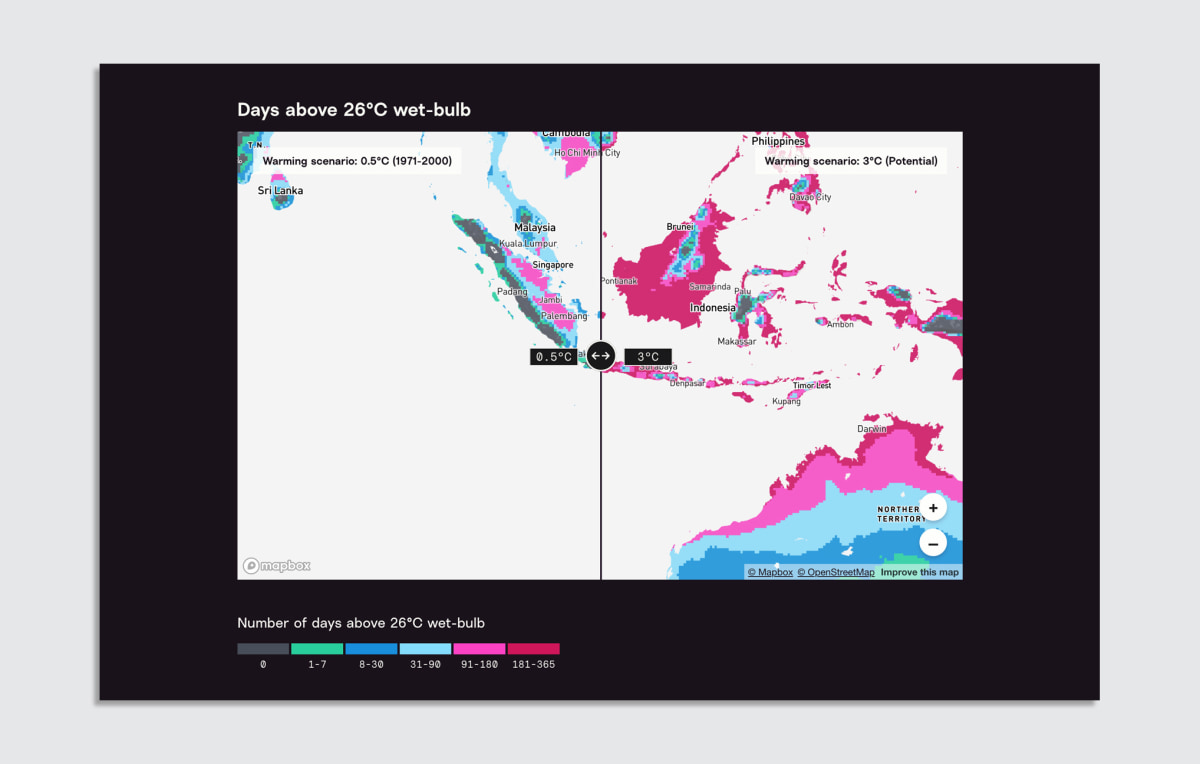

Spencer came to Woodwell and found a team of people, including myself, who were game to experiment and partner together on his ideas. To engage people outside of climate science, and in partnership with the scientists at Woodwell, we developed maps showing what climate impacts would look like around the world in future warming scenarios. We found that these maps were extremely effective communications devices. They spoke volumes about the risk of climate change for many different places around the world without using words.

We observed that even when people knew intellectually that climate change was a concern, they deeply understood the severity of it after seeing these maps, and visualizing changes in drought, precipitation, heat, and wildfire. This process gave us all the confidence that these maps could be very useful to the world if made easily accessible to the public, and Probable Futures could do that.

How did you design these maps to help people truly understand these future climate scenarios?

Climate change is a physical phenomenon happening in the physical world, and there’s really no better way to show that than through maps. Maps are a way to fit a lot of information into a format that is immediately recognizable for essentially all humans. We all look at a map of the world, and we know where we are. When we were building the platform, designers led that process under the direction of our Creative Director, Tammy Dayton, who owns Moth Design Studio in Boston. We intentionally had a design-first process to prioritize the user experience and the aesthetics of the maps and platform. The climate scientists and engineers worked collaboratively with the designers and, ultimately, we were able to build a beautiful and intuitive climate literacy platform that accurately represents the science.

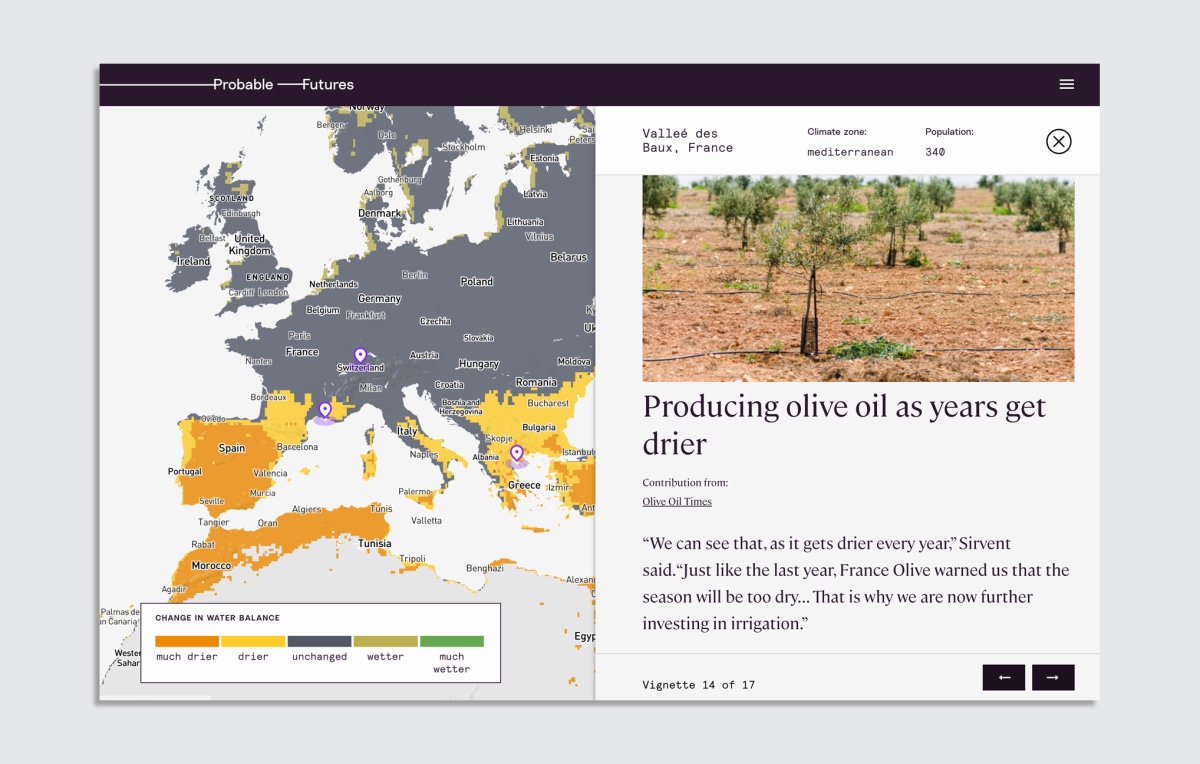

When building the maps, one of the most important factors we considered as a team was which climate science questions would appear on a map. We wanted the maps to be resonant and relatable. We asked questions like, how many days will there be above 95 degrees? That 95-degree threshold is important for agriculture because the production of crops such as corn goes down precipitously when there are sustained temperatures above 95 degrees. We ask questions about wet-bulb temperature, a combination of heat and humidity, which at certain levels the human body simply cannot survive in. We ask climate models questions about human physiology, the food that we eat, or where we can live, because these are relevant in our day-to-day lives.

What are some ethical considerations to make when envisioning future climate scenarios?

One of the main reasons we created Probable Futures was to democratize climate science. Climate model data tells us a lot about what future climate impacts will be like and feel like in different places around the world. That information should be accessible to all of us, especially the people and the communities that are most vulnerable and threatened by climate change. When we started working on Probable Futures, there was an industry of climate intelligence service providers that were packaging and selling this data for a very high fee to communities that could afford it. But in most cases, the communities that need this information most probably have the least ability to pay for it. That’s why we wanted to democratize the data, and provide climate literacy material, so that people know how to effectively use it.

Can you tell us a bit more about how you promote diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice?

We try to bring in operational partners from different parts of the world and that have teams that have different lived experiences. We’ve also launched our site in Spanish, French, and Chinese by working with translators that helped us capture the voice, tone, and intent of Probable Futures in their own languages.

Another way that’s a little bit different is, throughout the maps you will see these little purple markers. These each represent stories of risk, resilience, and adaptation in different parts of the world. We crowdsource these stories from different contributors and media outlets globally to highlight how people are experiencing and coping with climate change, from indigenous and agricultural communities to local banks and governments. The idea is not for these stories to be a comprehensive inventory of every possible impact of climate change, but to get the gears turning for users and help visitors to the site put themselves in the shoes of others living in very different geographies.

What are more goals and aspirations you have for the organization?

The two top line goals of Probable Futures are to democratize climate science and to build societal climate literacy. We would love to see the Probable Futures maps and data integrated into lots of different systems. We are working with a supply chain software company that is integrating the data and we’re helping them build functionality around it, so that supply chain officers can do climate risk assessments, having climate awareness be a standard part of their work processes. That could be done for countless other SaaS platforms whether you’re in business or film or education.

We have been cultivating what we’re calling the Probable Futures data community by offering them the use of power user tools. One of these tools that we call Probable Futures Pro allows people to import non-climate data into our climate data visualizations and explore it spatially in our climate maps. For example, I could bring a data set of all power plants in the world into our “days above 90 degrees” maps and see the intersections between climate risk and the human built world.

For the other aspect of building societal climate literacy, we’re partnering with different organizations to customize our materials for their audiences. We recently partnered with an organization called SubjectToClimate, which has a searchable database for resources and lesson plans available for K-12 teachers. That organization and their team of educators took our materials and created lesson plans for students in the classroom setting. In general, we seek out partners that can be ambassadors for different communities. Probable Futures doesn’t rely on our team knowing about every industry and about every community. Instead, we help other organizations to bring these resources into their community in whichever way makes the most sense for them.

How has this shaped your outlook on climate’s future?

For basically all of civilization, we had climate stability. If you look back into history, humans were originally a nomadic hunting and gathering species because the climate kept changing. Once the climate stabilized, that’s what gave us the ability to stay in one place, practice agriculture, and invest in infrastructure. Eventually all of that led to the complex society we have today. People have that “aha!” moment when they recognize that civilization was predicated on a stable climate. Now that we are moving out of that stability, we need to learn how to live in a world where the climate does change. We’ve never maintained civilization in a changing climate before, so we’re going to need new skills and tools to live and thrive in that new paradigm.

Figuring out how to live well in a changing climate means building resiliency, adapting to the warming that is assured, and mitigating the most extreme outcomes while also prioritizing the communities that are on the front lines of climate change. I am a mother, and you don’t have to be a parent to care about the next generation, but I envision a world where my kids and other people’s children still get to enjoy this amazing planet we live on. We often get caught up in the idea that Earth is not going to be as great as it once was, but it’s still the best planet in the galaxy. It’s always going to be way better than Mars. Even if it’s a little less perfect, we can still find community and joy and gratitude in that world.

Do you have any advice for creative people who are interested in working in the climate field?

I would say, you don’t have to change your job to work on climate change. It’s really about incorporating climate, so I encourage people to build their literacy in it. Literacy doesn’t mean having expertise. It means having a fundamental understanding and continuing curiosity. If you want to start incorporating climate into your design work, your media, your film, your storytelling, spend some time on the Probable Futures platform and you’ll get a long way with your climate literacy. Eventually, all work will incorporate climate in some way, and the sooner that happens, the better off we will all be.