- | 8:00 am

NASA’s Apollo 11 moon quarantine was hiding a dangerous secret

According to a new study, return protocols for the landmark space mission weren’t as safe as we were told. It’s something to consider as we eye Mars.

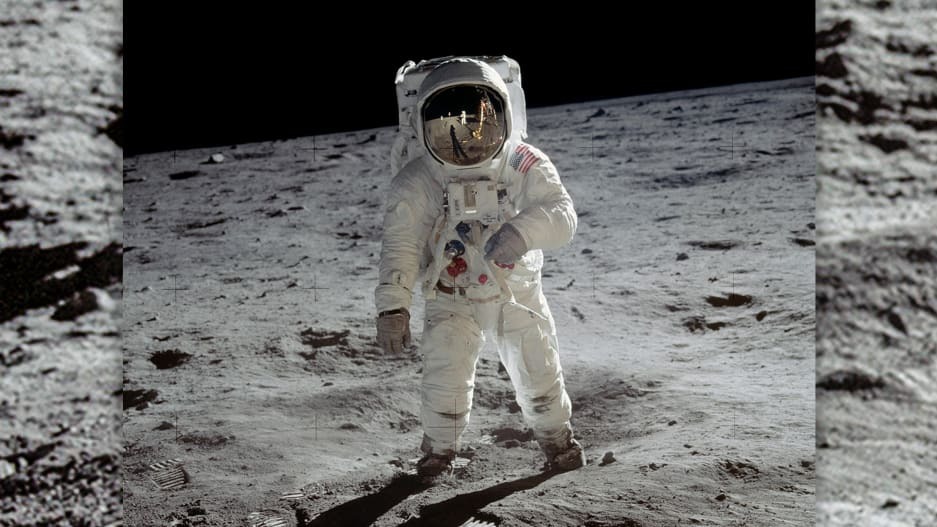

In the summer of 1969, after Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins took their “one giant leap for mankind”—setting foot on extraterrestrial soil for the first time in human history—they piled back into their rocket ship, returned to Earth, and were congratulated by then-president Richard Nixon, who greeted them as they huddled in NASA’s specially constructed moon quarantine chamber, meant to safeguard the planet against any apocalyptic lunar pathogens that might be borne by the spacefarers.

An iconic photograph was snapped.

But according to a June study from Georgetown University—more than half a century later—those planetary defense efforts may have been a bit of a farce. Nixon was, possibly, in harm’s way.

“To a degree previously unknown, the Apollo quarantine protocol suffered from numerous containment breaches that would likely have exposed the terrestrial biosphere to contamination—had lunar microorganisms actually existed,” the study’s lead author, Dagomar Degroot, wrote.

That they didn’t exist was celestial luck—although, to be fair, NASA had calculated for that break. The agency knew there was risk that the moon might harbor foreign microbes, ones that could devastate Earth with biodegradation or lunar fever. Such indecipherable threats could be world-ending. However, scientists also knew the chance of any microscopic life existing on the moon was slim.

Just look at it—in its cold, desolate perch, Degroot noted.

This was why, he argues, that despite spending well over $100 million on anti-contamination efforts in the 1960s, the Apollo mission’s post-return protocol was riddled with errors that were hidden from the public. Like the sleek metal chamber from which Armstrong and crew peered out, it was mostly for show.

Tens of millions were funneled into a state-of-the-art quarantine facility, the Lunar Receiving Laboratory, where some sterilizing equipment was cracked or melting. The astronauts’ suits leaked, too, and all parties involved soon discovered that moon dust, like confetti, was everywhere and impossible to clean.

The laboratory itself was relatively moot, anyway, as the astronauts were instructed to open their shuttle’s hatch in the Pacific ocean upon return, where any pathogens could have flooded out.

“If lunar organisms capable of reproducing in the Earth’s ocean had been present, we would have been toast,” John Rummel, a former NASA planetary protection officer, told the New York Times.

THE WILL OF THE UNIVERSE

For NASA, it all stemmed from a grander design. They were aware of the flaws in the protocol, but had long ago determined that lunar pathogens were a distant possibility—and if they did hitch a ride to Earth, quarantines would probably be futile anyway, doomed to failure.

Instead, managers and engineers concentrated their time on fixing technical flaws that could endanger Apollo 11’s success in space. They were “able to prioritize high-probability risks to individual astronauts and machines over low-probability risks to American society,” Degroot wrote.

However, this space-age narrative—in which scientists forego existential but unlikely threats in favor of less catastrophic, but likelier disasters—looms large over the coming decade’s Mars missions, as countries race once again to shoot humans to the red planet. It’s a cosmic land that’s far likelier to host alien life than the moon: Recent research suggests microbes may have flourished in Mars’s crusty underworld 3.5 billion years ago, and could still be buried in ice 30 feet below its surface, waiting in cryostatic slumber.

As Degroot notes, the underlying philosophy of confronting the likely over the unlikely, regardless of scale of consequence, is also often applied to nuclear weapons, artificial intelligence, and climate change, three arenas that are growing more supercharged and perilous than ever as we head into the 2030s.

To exercise this thought feels foreboding, if still a mathematical necessity. Because no matter how far in the shadows, the threat will always lurk, holding our future in suspension: If alien forces don’t destroy earthlings, then, will we destroy ourselves?