- | 9:00 am

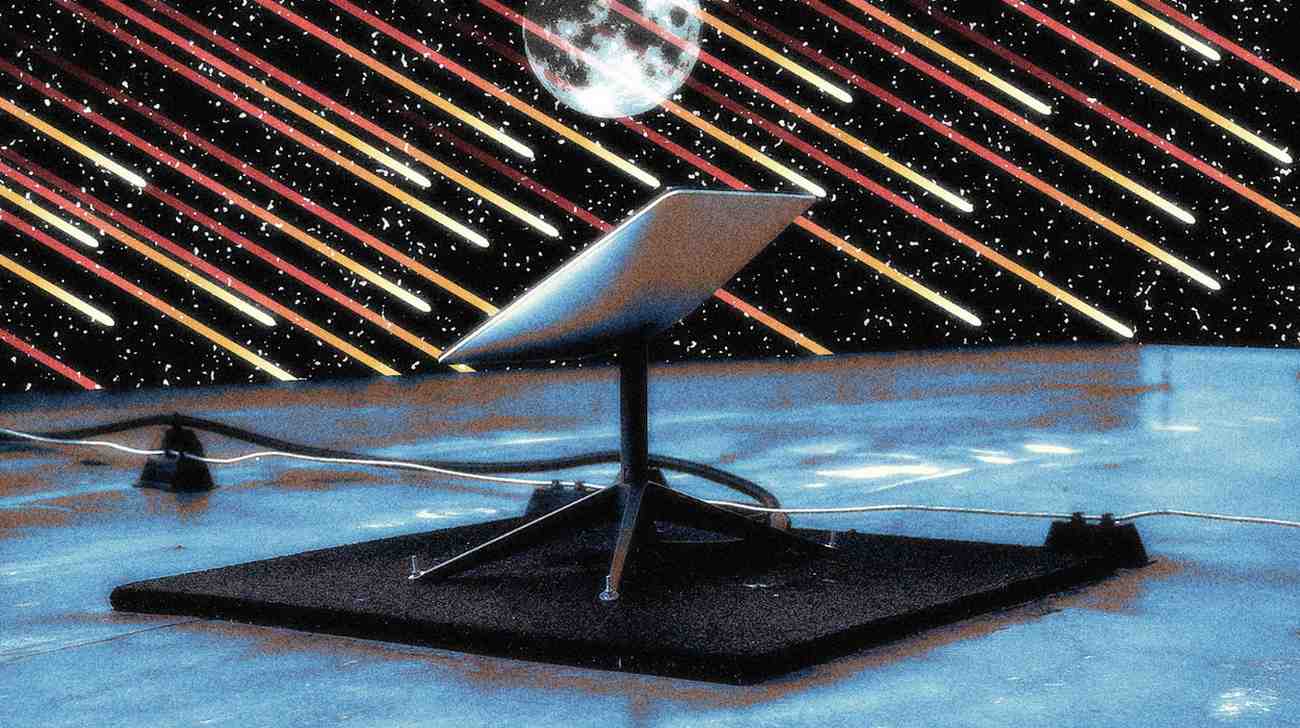

Starlink satellites are already falling, and it will only get worse

Elon Musk’s satellite network is expected to balloon in size over the next decade. Should we be concerned?

SpaceX’s Starlink orbital internet satellites are falling out of low earth orbit at an increasingly alarming rate, with one to two satellites now reentering Earth’s atmosphere every single day. According to Harvard-Smithsonian Center astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, that number will only go up as more satellites end their useful lifetime and the low earth orbit (LEO) constellation numbers skyrocket. This is as much a design problem as anything.

While the numbers vary, right now there are around 10,200 active satellites in low earth orbit. Of those, about 8,475 are Starlinks. In other words, about 80% of all those satellites belong to Elon Musk’s company.

By 2030, the European Space Agency expects the number of satellites in LEO will increase to about 100,000. This is mostly thanks to SpaceX—which plans, pending regulatory approval, to expand its fleet to a staggering 42,000 satellites—but also to Starlink-clone networks like Jeff Bezos’s 3,200-satellite Kuiper, and the Chinese GuoWang and Qianfan, which plan to launch a total of 18,000 units combined.

Designed to fall

Each Starlink satellite has a five-year lifespan. They zip across the sky in low earth orbit. There, objects still feel about 95% of the gravity we experience on the ground. What keeps them from plummeting is their sideways velocity of 17,000-plus mph.

These vehicles are essentially falling around the Earth, inches at a time. But even at that altitude, the thin atmosphere creates drag, with air particles hitting and slowing the satellites down. To compensate, they fire up their onboard krypton and argon thrusters, which lift them up to maintain their orbital path. When the fuel runs out, the satellite can no longer boost, its orbit decays, and it comes crashing down.

Before that time comes, SpaceX de-orbits the satellites on a controlled crash, allowing them to aim at an empty stretch of ocean as opposed to making a random entry.

Why this is a problem

As McDowell explains—and SpaceX itself admits—some satellites will not disintegrate upon reentry, though they are designed to do so. “They [Starlink satellites] are designed to completely burn up,” McDowell said in a recent interview with EarthSky. “Now we’re not sure we really believe that they really burn up, but at least for the most part they melt.”

There have been many other incidents of space objects falling to Earth, including big chunks of space stations like the American Skylab and the Soviet Salyut 7; parts of rockets like a European Ariane 5 nose; satellites like the Russian Kosmos 2251 (which collided with an Iridium communications satellite); and even the trunk of SpaceX’s very own Crew-9 Dragon spaceship.

But thanks to the extraordinary number of units deployed, the Starlink constellation represents an outsize concern to everyone on Earth—and also to other satellites in low earth orbit. If one of Musk’s satellites crashes against another satellite, it could start a chain reaction called the Kessler Syndrome, which you can see in action in Alfonso Cuarón’s film Gravity.

This is the nightmare of runaway debris collisions devastating all low earth orbit satellites. A single crash could create cascading debris fields, wiping out the infrastructure of global GPS, communication, financial systems, and weather monitoring. Worst-case scenario, it could plunge civilization into chaos. Right now, SpaceX is essentially launching bullets into an orbital game of Russian roulette.

With thousands of Starlink satellites circling the globe, McDowell says that the current de-orbit rate is just the beginning. As the first generation of Starlinks reach their five-year expiration date, we are seeing four or five satellites per day being intentionally plunged back to Earth. This number is set to multiply as more and more Starlinks get to their end of life. As the constellation grows into the tens of thousands, we risk turning our upper atmosphere into a perpetual fireworks show of burning toxic metal that sometimes crashes into Earth.

Designed for “full demise”

Back in July 2024, Musk’s company assured regulators and the public that its satellites were designed for “full demise,” claiming they would vaporize into harmless dust. That turned out to be fantasy: Eight months later, New Scientist revealed that a 2.5-kilogram chunk of aluminum from a Starlink satellite slammed into a farm in Saskatchewan, Canada. SpaceX was forced to admit that this piece—a modem enclosure lid—was supposed to have vanished completely but didn’t. Musk’s safety guarantees were proven wrong by a 5-pound piece of metal lying in a farmer’s field.

SpaceX claims this has happened only once with a satellite that was part of a failed launch. However, in January 2025 a new fireball crossed Chicago’s sky. As he posted on X at the time, McDowell believes this was Starlink-5693. In response to McDowell’s post, Michael Nicolls, VP of Starlink engineering at SpaceX, said it was an uncontrolled reentry caused by a faulty component. The worrying bit of his explanation: “There is still work to do to guarantee this, especially for satellites with degraded attitude control. But as you noted, the sats nearly completely demise upon reentry.” [my emphasis]

Too much junk

SpaceX now claims it uses a “belt-and-suspenders approach” to safety, the nerd way to refer to using multiple redundant systems to prevent a single point of failure. It says the risk of human harm is “less than 1 in 100 million.” The company has said that for its Starlink V2 Mini satellite, about 5% of a satellite’s mass could potentially survive reentry, but insists it’s mostly harmless silicon fragments with the impact energy of a falling apple.

Musk claims his latest Starlink V2 satellites are designed with better altitude and attitude controls to target reentry corridors with high accuracy—roughly within 10% of an orbit ground track, which translates to about 10 minutes of flight time. SpaceX says it conducts plasma chamber tests simulating atmospheric conditions to better understand how components break up during reentry, seeking to improve prediction of debris survival. But no matter the improvements, every new satellite launched adds to an increasingly fragile orbital environment. SpaceX hasn’t replied to Fast Company’s request for comment.

But there’s more to consider beyond potential bodily harm. As these satellites burn up, they pollute the stratosphere with metal particles, creating what scientists call “anthropogenic meteor showers.” Researchers are now raising alarms that these metals, particularly aluminum, could linger for years and catalyze the destruction of the ozone layer.

Atmospheric chemist Daniel Murphy told Science magazine in November 2024, “Almost no one is thinking about the environmental impact on the stratosphere.” Laser mass spectrometry studies detected elevated levels of lithium, aluminum, copper, and lead in the stratosphere, exceeding natural meteor input. These metals come from satellite reentries and may nearly double natural metal aerosol concentrations, threatening ozone protection.

Currently, about 2,000 satellite reentries per year emit 17 metric tons of aluminum oxide nanoparticles into the stratosphere. The figure is rapidly rising as mega-constellations multiply. Astronomer Samantha Lawler told Science, “We can’t keep using the ground and the atmosphere as a dumpster.”

Here’s how the European Space Agency CEO Josef Aschbacher warned about the existence of Musk’s satellites to the Financial Times back in 2021: “You have one person owning half of the active satellites in the world. That’s quite amazing. De facto, he is making the rules. The rest of the world including Europe . . . is just not responding quick enough.”

We are watching as a billionaire’s unchecked ambition reshapes the orbital commons without real oversight. Space isn’t meant to be Musk’s backyard. While humanity pays the price, Musk just shrugs and keeps aiming at planetary domination.