- | 8:00 am

Steve Jobs predicts the rise of GenAI in this never-before-seen video from 1983

A new online exhibition at the Steve Jobs Archive shows just how prescient the Apple founder’s vision for technology really was.

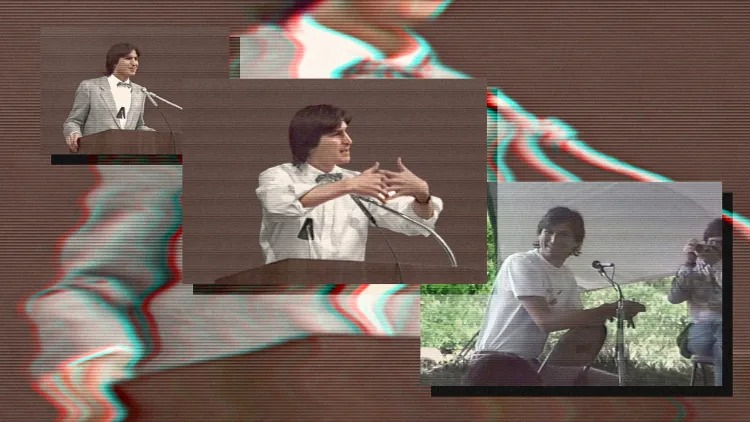

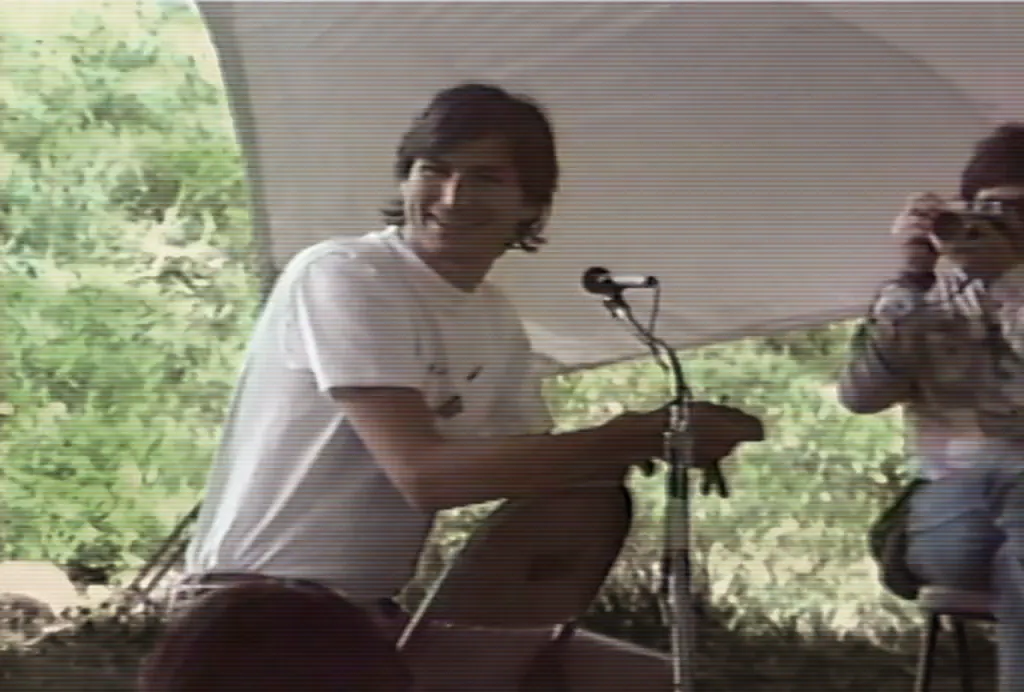

The year is 1983 when a 28-year-old Steve Jobs takes the podium at the International Design Conference in Aspen.

Apple has recently released the Lisa computer, and the Mac will be introduced the following year. Surrounded by an audience of hundreds of designers, Jobs asks for a show of hands of people who own an Apple computer—or any computer at all. The room is awkwardly silent.

“Uh-oh,” he says with a laugh.

Undeterred, Jobs—who is still in his bow tie era—casually rolls up his sleeves before outlining what a computer is, how software works, and what the next 40 years of advancements could look like, all with incredible foresight.

You can watch the video for yourself, which is the cornerstone of Objects of Our Life, the newest online exhibit at the Steve Jobs Archive. While some audio from the talk was published in 2012, this is the first time Jobs’s full presentation at Aspen has been made available. It’s presented alongside a few additional videos from the weekend, an opening letter from Apple veteran Jony Ive, and an article from historian Leslie Berlin, the executive director of the archive.

“He’s this incredibly experienced guy on the one hand . . . and on the other hand, he is really kind of coming to a deep, deep love of design,” says Berlin of Jobs in this era. “Now he sees how it’s going to blend with all the things he understands about technology and business. And he’s just excited to pull it forward and get the design community engaged . . . around all of this.”

Indeed, Jobs is clearly using the speech in part as a recruiting tool. He explains that while the car had been the predominant object of modernity, that focus was about to shift as people would soon be spending “two to three” hours a day at a computer. He makes the case for America to become a hub of design, and for designers in the audience to realize that by building the best computers the world has ever seen.

“One of the reasons I’m here is because I need your help. If you’ve looked at computers, they look like garbage. All the great product designers are off designing automobiles or buildings. We’re going to sell those 10 million computers in ’86 whether they look like a piece of shit or look great . . . and it doesn’t cost any more to make [them] look great,” Jobs says.

“Most of the objects in our life are not designed in America,” he continues a few beats later. “We have a chance, focusing on this new computing technology, of meeting people in the ’80s.”

Along the way, Jobs outlines the future he imagines, describing computers as a new medium of communication that we will get wrong at first, much like the first decade of television was really just radio programming filmed on a camera. He teases how computers will shrink smaller and smaller—“We want to put a great computer in a book. . . . Right now it fits in a bread box”—and how radios will connect computers to one another, allowing us to meet to explore niche interests. He describes a demo that sounds just like Google Street View (and laughs alongside the audience at the complete lack of discernible utility), while suggesting a whole economy built on software will redefine the economics underlying companies and products.

“What I think is so important is he’s saying, ‘I don’t know exactly how it’s gonna end up in your house, I don’t know exactly how it’s gonna end up in your office, but I can tell you it is,’” Berlin says.

Even in this early speech, you can see some of Jobs’s most recognizable motifs begin to gel—from his casual use of “one more thing” to his early attempt at verbalizing a manifesto that he’d articulate 30 years later, in which he reconciles the many overlooked gifts of culture and his urge to contribute something in return. But what I found most gut-dropping landed at the end of his 20 minutes of prepared remarks, when he began to articulate the true potential of software in a description that sounds strikingly similar to the generative AI large language models we have today.

“Going to school I had a few great teachers and a lot of mediocre teachers, and the thing that probably kept me out of jail was books. Because I could go read what Aristotle wrote or what Plato wrote, and I didn’t have to have an intermediary in a way. And a book was a phenomenal thing. It got right from the source to the destination without anything in the middle,” Jobs says.

“The problem was, you can’t ask Aristotle a question. And I think as we look at the next 50 to 100 years, if we really can come up with these machines that can capture an underlying spirit, or underlying set of principles, or any underlying way of looking at the world, then when the next Aristotle comes around, maybe if he carries around one of these machines with him his whole life, his or her whole life, and types in all this stuff, then maybe someday after the person’s dead and gone, we can ask this machine, ‘Hey, what would Aristotle have said? What about this?’ And maybe we won’t get the right answer. But maybe we will. And that’s really exciting to me, and that’s one of the reasons I’m doing what I’m doing.”

Jobs was brilliant in many ways, but this presentation reminds me that his most enviable skill was that of translation—of taking the headiest of technologies, reframing them as metaphors we all understand, and then, rather than just stopping there, using the core insights behind those metaphors to navigate the boundless potential of technology when articulated through design.

Objects of Our Life is free to explore now.