- | 8:00 am

The future of the tech office is taking shape in Asia, not Silicon Valley

Out with the gimmicks and in with good design.

Over the last quarter century, the tech company office has become its own sub-genre of architecture. It’s the type of building that, whether through hubris or extreme wealth, eschews the buttoned-up standards of conventional offices. There are bright colors, playful work settings, plentiful social areas, and an abundance of extracurricular activities that range from game rooms to movie theaters to whiskey bars. From the dot com bubble of the late 1990s to the rise of Google and Facebook, the tech office steadily transformed into manifestations of a new kind of freewheeling capitalist philosophy of failing fast and scaling up, but making it all look like fun.

Silicon Valley birthed this tech office model. But, according to architect Ole Scheeren, the future of the tech workspace is now being rewritten on the other side of the world.

Asian tech companies are putting a more serious and more humane face on the workspaces of emerging tech giants, according to Scheeren. He’s spent the past two decades designing large-scale and head-turning projects across Asia, most notably the contorted CCTV tower in Beijing in 2012, which he co-designed while a partner at the architecture firm OMA. Scheeren followed this by launching his own firm, Büro Ole Scheeren, and has pumped out a string of large-scale urban projects across the region ever since.

Increasingly, these projects are mixed-used developments that will serve as the headquarters of major technology companies. Three such Scheeren-designed headquarters projects are currently underway in Shenzhen, China alone. “I think all of them are very clearly posing a question of what the new headquarters model should really be like,” he says.

What that model probably won’t look like is the carefree, recreation-centric campus design of Silicon Valley’s early 2000s boom times. “There’s a very clear direction that’s going away from the gimmicky world that the tech offices largely in America had cultivated,” says Scheeren. “The London bus as the meeting room, or a series of gimmicks and perks that tried to declare the office almost a children’s playground rather than a serious workplace.”

In Asia, and particularly in the projects his firm is designing in China, Scheeren sees the pendulum swinging back toward more serious office spaces that balance the day-to-day social and physical needs of human beings, while enabling tech companies to achieve their breakneck growth.

A NEW KIND OF HEADQUARTERS

One of these projects, revealed here for the first time in exclusive images, is the forthcoming Shenzhen headquarters of JD.com, China’s largest digital retailer. A two-tower megablock covering more than 2 million square feet, the project is a mix of offices, retail, a museum and exhibition hall, and publicly accessible courtyards and plazas throughout its podium. Running up and wrapping around the sides of the towers are large cutaway sections that create space of terraces and balconies that give each floor multiple points of access to the outdoors.

The prompt from the project’s design competition was to create a headquarters that integrated itself with the surrounding city while also nurturing a relationship with nature. Scheeren says the COVID-19 pandemic influenced his interpretation of that prompt by giving workers easy and frequent points of contact with exterior spaces. These cutaway parts of the facade are a more useful version of the cheeky amenities built into tech headquarters of the past. Scheeren calls them the social spines of the towers, which are currently under construction and expected to open in 2026.

But the outdoor access isn’t a sacrifice for the business side of the headquarters. Scheeren says the design integrates the exterior space without cutting away much needed workspace and office infrastructure. “Even though it’s so dominant in the architecture, it still leaves very functional and rational floor plates. So, it’s not a system that calls everything into continuous question.” The access to the exterior, he says, “is able to coexist with a sense of efficiency throughout the space.”

THE OPPOSITE OF TECH

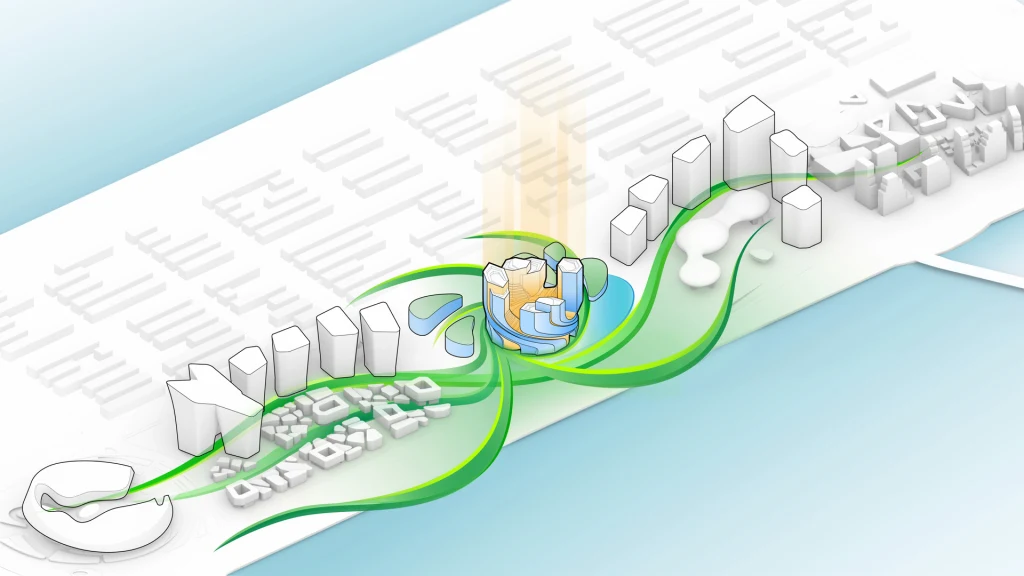

Another forthcoming project is the significantly larger headquarters of Tencent, the video game and technology conglomerate behind WeChat. About twice as big as Apple’s spaceship-like campus in Cupertino, California, Tencent’s new headquarters will be a swirling ring of towers that converge in a park-topped central base that includes collaboration spaces, a conference center, public plazas, a health club, and a variety of recreational spaces for employees and the public. Covering roughly 5 million square feet, it’s a megadevelopment that aims to become a new urban center in the city. Construction will begin later this year.

Inside the ring of four towers, which Scheeren refers to as “the vortex,” a new kind of working area will emerge, with a mix of informal collaboration areas, terraces and outdoor park spaces, and city-like retail and hospitality spaces for lunch meetings or a just a break from the formal office spaces in the towers above. “The efficiency of the towers and the workspace converges with a sense of connectivity to the ground. All the social spaces and that mixing chamber in the middle creates a very focused space for collaboration and communication,” Scheeren says. “That literally and formally fuses the towers together, but of course, also functionally really creates a sense of togetherness.”

Büro Ole Scheeren’s third Shenzhen tech headquarters project is more inward-facing than the other two, but with its own unique take on the mixing and movement of people within an office setting. Designed for the telecommunications company ZTE, the building is of the massive spaceship variety, with a stack of rectangular floors that are twice the size of football fields, sliced through by a diagonal atrium ringed with staircases, gathering spaces, and informal meeting areas. “This is like a giant circulation space that seamlessly and gradually penetrates the building and connects everything,” Scheeren says.

When the building finishes construction in about a year, the atrium will be topped with a dome of glass, underneath which is a large indoor garden. Access to nature, either through outdoor terraces or indoor gardens, has become a recurring theme in the tech headquarters Scheeren’s firm has designed. These companies, he says, “want to be balanced with something that is really the opposite of tech in many ways.”

That desire is shaping this new breed of tech campuses and offices, making them more integrated with the natural world, or at least bringing in parts of the natural world people have come to value more highly than in the past. “While at some point the office was the office and when you had to get away from the office you really had to get away, I think now there’s a recognition that it’s no longer city against countryside,” Scheeren says.

In the tech company projects his firm is designing in China and across Asia, Scheeren says the blending of spaces—formal offices, informal meeting areas, urban commerce districts, public plazas, nature—is setting a new standard for commercial real estate that could find relevance beyond the region. “The fundamentals of those ideas are absolutely globally applicable and globally relevant,” he says. Just like the fun-loving headquarters of Silicon Valley’s boom times, this emerging class of tech headquarters could set a new standard for the ways tech companies work.