- | 9:00 am

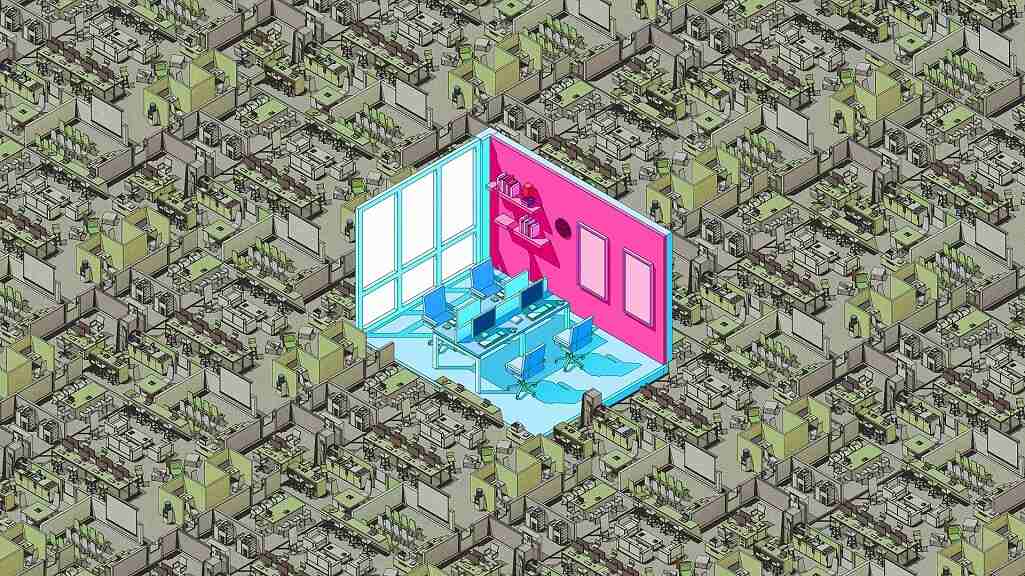

The rise of the ‘Goldilocks’ design company

To scale or not to scale? That has always been the question for entrepreneurs. Today, more designers are opting out of big companies and freelance life to build small studios of their own.

Not long ago, Austin Dunbar moved his design studio, Durham, from a 750-square-foot space to a 16,000-square-foot building—but if there’s one thing he does not want to fill it with, it’s an endless supply of employees.

Rather, he and his team of eight in the Cincinnati region occupy one floor; another is for hosting clients from out-of-town and brand-building sessions; another is dedicated to video and photo services; and another is simply a full bar and recreation space.

Dunbar isn’t alone: If you take stock of the creative world today, you’ll likely notice that the desire to quickly scale head count and build the next agency behemoth feels has fizzled in the design world. While concrete industry data on studio size can be hard to find, in talking to designers, many agree that small studios—be they two people or 20—are, for the moment, the sweet spot of building a design practice.

Some creatives found themselves launching or joining smaller shops amidst the Great Resignation (and great bouts of layoffs) from major corporate players. Others never wanted anything to do with the industry giants in the first place, and cautiously scaled by necessity as their freelance practices grew (according to GD USA, the number of freelancers has grown by 3 million each year since the pandemic).

For others, starting a small studio was just the logical path. Take Dunbar. He started his career designing for global agencies, and soon found himself in an environment he describes as an anti-collaborative, anti-creative pressure vacuum beset by endless layers of management between designer and client. When it came to feedback, “the funnel is just so big, and by the time it gets to you, it went through the creative director with his feet up on a desk, it went through the business director that has a zoology degree that knows nothing about creativity . . . ”

At the last big hub he worked for, he asked for a raise—and says he was given a $100 prepaid Visa instead. In return, he gave his two weeks’ notice.

“I was doing $3 million worth of work by myself. I was the only designer on the whole project. And I was making $55,000 a year. I was like, this is a math problem. I’m super fortunate and super lucky to have been able to work at these big globals to learn what to do—but more so, to learn what not to do.”The question of whether to scale—and how much to scale before you become what you set out to avoid—is top of mind for many practices today.

WORKING 1:1

Before founding the graphic design studio Design Army, Pum and Jake Lefebure were running a creative department of around 100 people.

In such an environment, “It’s always about taking the project to pay the payroll,” Pum says. Creativity takes a backseat. So the two left and started Design Army around their kitchen table in 2003. Lefebure’s goal from the outset: “I didn’t want to build a big place with no soul.”

Today, Design Army operates with around 20 people. At its peak, the studio grew to 30—but the quality began to suffer, Lefebure says, so they scaled back. On the whole, she likens it to a boutique hotel. On vacation you could stay at a perfectly fine chain, but the boutique hotel is uniquely focused on service and craft. There’s a concierge desk. Rather than calling a 1-800 number with a question or issue, you can deal directly with the proprietor.

For Dunbar, that’s key.

“Our whole business is predicated on personality and working with people, and not like, Oh, I can’t give you that answer because I’m not that person who can say yes or no—but I can get ahold of X, Y and Z colleague, and we’ll have to have a meeting about it, and in two weeks, we’ll get back to you all,” he says. “Everyone knows who the chefs are in the kitchen.”

For nearly all the people interviewed for this story, those tangled layers were a critical reason for opting out of the major behemoths and staying small—as was the quality of work that can be achieved from a more 1:1 model.

Jonny Black, principal of the studio The Office of Ordinary Things, started with a team of two, scaled to five, went back to two, and is currently in the process of assessing his next moves. When his team was bigger, he found himself entrenched in more admin work. “I didn’t start a design studio because I want to do a bunch of emails. I started it because I wanted to do the work,” he says. “I would say the scale of a studio gives you a sense of how much they care about the business side of things—and there’s nothing wrong with that. But I think if you really care about the quality of the work, you’re going to be under eight people.”

SWISS ARMY LIFE

Before going solo and eventually launching the brand-building studio Practice, Michelle Mattar spent some time working in other shops. She was not a fan of the “us vs. them” dynamic at agencies when it comes to clients—and she also didn’t understand why the business was often so siloed (strategists, designers, etc.) when everyone was working on the exact same project.

So at Practice, today there are no project managers or client directors—rather, she wanted a crew that was working and thinking on initiatives in sync.

“I think one of the biggest advantages of staying small is that we are connected real time to the problems that we’re solving,” she says, noting that Practice is currently a five-person team, with the ability to flex to six or so. “I often joke that my happy place is an UberXL.”

When it comes to Lefebure’s approach to team size, she holds up a sketch she made of a Swiss Army Knife, with its various unique implements extended. Having fewer people means having more senior people, she says, and she scales by discipline—animation, film, fashion, and so on. With experts in all of Design Army’s various capabilities, they can then bring in specialist freelancers depending on the project at hand.

“The strategy is to be an elastic design company, an elastic brand, so you are able to go small or stretch big, depending on what the need is,” she says.

Ultimately, Lefebure says Design Army is often regarded as an extension of a client’s in-house creative team—and that’s a boon that comes with being small and boutique.

Dunbar brings up another: speed.

“We’re nimble and mutable and fast enough to be able to get stuff done and proof of concept and have everything in round one look like it’s ready to go to market, versus spending eight months on strategy . . . because [an agency] want to upfront this whole thing to make a bunch of money,” he says.

When you’re smaller, he adds, you have to be transparent with costs and hours—and that also benefits the client, making for a more desirable partnership. Back at the office, there can be more money to go around when you’re doing well. Some of the studios in this article do profit-sharing. Dunbar says he also offers a 6% 401(k) match and cash bonuses on top of highly competitive salaries.

“Staying small financially enables me to help take care of people better, and to have better relationships with the bankers and everyone else, because you’re not talking to a board of directors,” he adds.

THE PERILS OF SCALE

In a design world beset by corporate layoffs and #OpenToWork badges, it’s no wonder that many talented creatives are actively hunting for an alternative to the bigs—but there are, of course, concrete downsides to staying small, too.

Notably, as Lefebure and others said: you work—a lot. And you’re never really off. Before he brought on a team, Dunbar says his work sent him to the ER three times with heart problems and other maladies.

There’s also the challenge of being disregarded as serious contenders for blockbuster projects from gigantic clients. Or getting bottlenecked. Or, as Aron Fay of FAY Design points out, not being able to churn out a beautiful case study or do internal marketing as easily. Or, as Mattar notes, accidentally scaling—i.e., a great project comes along that you believe in and want to support, so you grow your team with it.

“Accidental scale is something that happens when you do sell time—and if you’re not careful and you don’t think about that thoughtfully, you can totally change the trajectory of your business just by saying ‘yes,’ and not by strategizing around what that opportunity cost is,” she says.

THE PENTAGRAM PARADOX

Mattar says she’s hearing from industry friends that massive firms are on their way out, but she’s not so sure. What she does believe is that being an all-in-one generalist studio is not seen as the advantage it once was. Rather, niches are where an operation can thrive.

On that front, Fay says he and his small team believe in being specialized and blending their output with their interests and passions—which has resulted in a lot of identity work, and collaborations with clients in tech, higher education, and the music world.

Before launching FAY, he spent six years at Pentagram on Michael Bierut’s team, where he witnessed the benefit of being able to work closely with clients without layers of bureaucracy.

The storied design firm is essentially a series of independent teams all working under one banner—a model that is perhaps ripe for widespread replication, offering the best of both worlds.

“I would love to see that,” Black of the Office of Ordinary Things says of the Pentagram model. “What I want to know is, why aren’t people already doing that?”

Take a look at the projects on Black’s website, or Fay’s, or anyone’s in this article, and you probably have no clue how big their teams are—and in fact, you’d probably think they’re much larger. Good output speaks volumes, and does so louder than a voluminous head count ever could.

“I always tell people that getting a sense of how a studio works and looking at the quality of their work is far more important than the size of the team,” Black says. “Because you can have a larger team and have chaos. Size doesn’t equal stability.”