- | 8:00 am

The saga of the ‘shrinkable sofa’ reveals an unfortunate truth about the furniture industry

In an industry notorious for chasing trends, true innovation is hard to come by.

As I write this, designerati have just finished their annual schmoozefest in Milan, where they traipsed the halls of the world’s most prestigious furniture fair. But while Salone del Mobile was in full swing, on the other side of the Atlantic a new kind of armchair was taking shape.

This armchair wasn’t dreamed up by a star designer, it isn’t made of white bouclé or velvet, and it isn’t launching on the world’s biggest podium. It is called the Shrinkable Sofa, and it’s a humble, modular piece of furniture that can transform itself, in a matter of seconds, from an armchair to a three-seat couch. Almost 10 years in the making, it was designed for a regular person with a regular job and a regular salary—and is launching on Kickstarter at the price of $1,499.

But this isn’t a story about the Shrinkable Sofa. It’s a story about a flawed furniture industry that prioritizes the bottom line over innovation, and about the invisible yet tangled logistical web that underpins the industry.

THE MIND OF AN INVENTOR

Daniel Chiriac, the sofa’s inventor, has always loved making things with his hands. He moved from Romania to Canada when he was 27, studied at Polytechnique Montréal, and currently works as a senior mechanical engineer at Sheertex. But he is a serial inventor at heart. “I am always looking around me to solve things,” he says one day over Zoom. “Everything that bothers me, I have a solution.”

Chiriac, now 47, keeps a running list of “at least 80 ideas” for his potential inventions and has amassed eight patents so far. These include a cockpit pedestal for Bombardier Aerospace (where he worked for seven years) and an adjustable ratcheting tool. But the Shrinkable Sofa is by far his biggest invention.

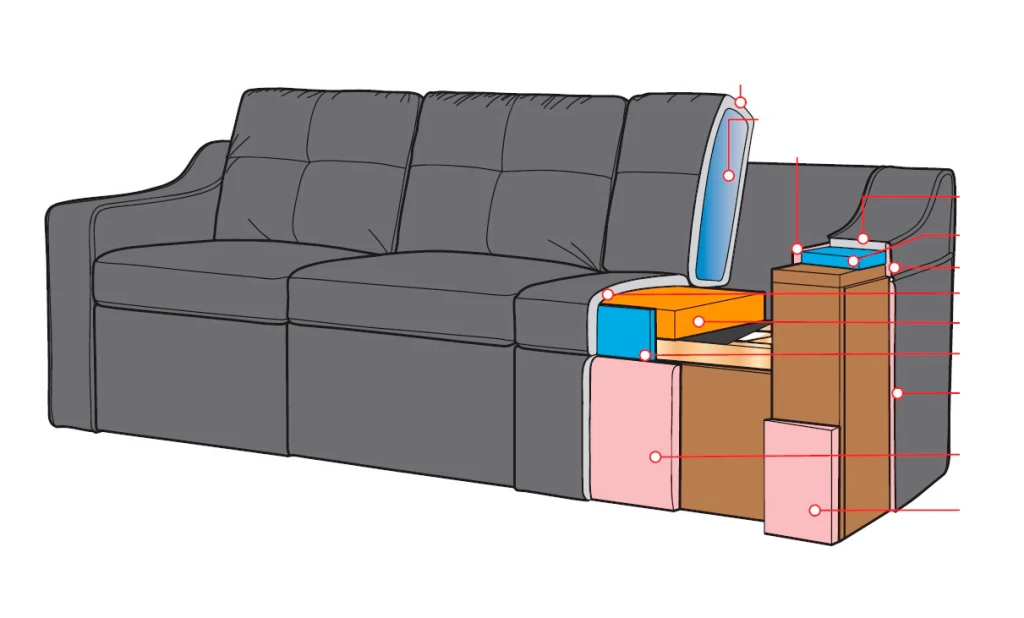

Through a series of clever mechanics, the sofa unfolds almost like a puzzle. Starting with an armchair, you pull one armrest to the right, remove the extra seat and backrest cushions from a storage compartment under the main seat, then slot them into the empty space. You can keep the love seat as is, or repeat the same process with the left armrest, and transform it into a three-seat sofa. The couch arrives preassembled in one giant box, and the transformation process takes less than a minute—no tools required.

In theory, the Shrinkable Sofa ticks all boxes for a successful piece of furniture: It’s easy to assemble, it has built-in storage, it’s modular, and it’s affordable. And yet its inventor has spent a decade trying—and failing—to convince furniture retailers that it would sell. The Kickstarter campaign is a last-ditch effort to make the Shrinkable Sofa a reality. “As an inventor, it’s frustrating because we are losing a lot of good ideas because we don’t have a system to bring these ideas to the market,” Chiriac says.

THE MANUFACTURING PROBLEM

Chiriac designed his first Shrinkable Sofa prototype in 2015. He pitched it to “hundreds” of companies, he says, and got hundreds of rejections, until one furniture manufacturing company in Quebec expressed interest. That company helped him build a more advanced prototype, then another furniture company out of California licensed it. As part of a licensing deal that gave the company exclusivity over the sofa, it helped pay for a utility patent that cost a mind-boggling $100,000. (A utility patent protects the way an object works and is harder to obtain, whereas a design patent protects the way it looks.)

For a minute, it seemed like business would take off. An earlier version of the sofa, which was clad in fabric and could transform only from an armchair into a love seat, was even picked up by Home Depot, Bed Bath & Beyond, and JCPenney, who distributed the sofa for a short period of time. But that version of the couch flopped and was quickly pulled off the market just in time for the pandemic to wreak havoc on supply chains around the world.

According to Chiriac, the couch flopped because it launched with zero marketing strategy. He says the distributors described the couch as a “love seat with storage” without mentioning its modular functionality, or explaining why this particular love seat was more expensive than standard love seats. As a result, he says sales weren’t aligned with the company’s high-volume strategy. (We reached out to the furniture company for comment and will update the story if we hear back.)

It took three more years for Chiriac to strike a deal with Turkish manufacturer Istikbal, but the company said it would only make the sofa in batches of 90, or enough to fill one shipping container. Chiriac had to find another retailer to help with sales (by then, the licensing deal with the California company had expired) as well as a fulfillment center to handle eventual online orders. He was flying solo once again.

We can all theorize about why Chiriac struggled so much to bring a seemingly novel couch design to the market. Maybe a shape-shifting sofa stands out too much in the sea of bland Instagram brands like Joybird, Floyd, and Burrow. Maybe it failed to capture furniture retailers’ attention, or maybe not making it flat-packed was shortsighted. (Several retailers were contacted for this story, including Ashley Furniture and Williams-Sonoma, but they did not respond to our request for an interview.)

The true answer may be much simpler: Big Furniture is not about innovation; it’s about profit. And if retailers don’t have any data to suggest that a “shrinkable couch” would sell, they likely won’t take the risk. Aaron Masterson, the founder of a small furniture store in Austin called Local Furniture Outlet, told me in an email that retailers are less likely to invest in a product if the market hasn’t already shown that it would be profitable.

“The typical life cycle of a newly designed piece of furniture usually starts in a high-end or boutique store,” he says. “Once a trend begins, the mid- and lower-end manufacturers knock off the original piece by using cheaper materials and outsourcing from factories overseas. Within two to three years, that new design that retailed for $1,000 in the beginning is now being sold for less $300 as a knockoff.”

Typically, retailers have to pay a licensing fee to sell an independent designer’s idea, as was the case with Chiriac. But Masterson points to a much more common practice: design by inspiration. “Unless the designer is a big name that would help drive sales, you only need to do a few slight modifications to avoid paying any type of licensing fee,” he says.

This kind of behavior betrays an uncomfortable truth in the mass-market furniture industry: The stakes are simply too high for the Ashleys and MillerKnolls of the world to invest in a new idea from a nonestablished brand. “The stuff coming out of furniture companies is not serving consumers, it’s serving either companies’ bottom lines or quarterly earnings. It’s not even a radical statement, it’s just the truth,” says Sami Reiss, who has been buying and selling furniture for 12 years and now runs a popular newsletter dedicated to vintage furniture called Snake.

Reiss believes that instead, many of the most innovative ideas in furniture come from younger, independent designers who have more freedom to experiment, and who tend to sell their furniture straight to consumers, bypassing large distributors.

WHERE NEW IDEAS COME FROM

The furniture industry might not be set up to support independent designers, but some have managed to break through the noise by finding a business model that works for them—and simply refusing to scale up. Take Lichen, the young studio that made waves during the pandemic with its design incubator in East Williamsburg. Ed Be and Jared Blake founded Lichen in 2017 with the intention of making good design accessible to more people (the bulk of their inventory was priced at less than $200).

The studio started out selling vintage furniture, but about a year after launching the founders realized that vintage furniture was finite and they had to start designing furniture from scratch to meet their buyers’ demand. They realized they could start making their own furniture, bringing a non-Eurocentric perspective to an industry that is full of it (Blake is Black; Be is Chinese American). “We definitely have roots in [mid-century design], but we’re also not trying to be so stuck . . . that we can’t see forward,” Blake says. “Do we have to talk about the Eames for another 150 years? We can’t.”

Perhaps ironically, the pair met over an Eames chair. Blake listed his on Craigslist, and Be went over to buy it. But today their studio’s inventory is made up of about half vintage and half new furniture, and they pride themselves on following a different path than their more traditional peers.

When the team ventured into the realm of new furniture, they started slowly. Instead of aiming for big numbers that only big manufacturers could deliver, they made their first coffee table in small batches of 6 or 12, then waited to see how buyers would respond at the studio’s brick-and-mortar location in East Williamsburg. (They’ve since moved to Ridgewood, Queens.) “You never want to run out, but you also don’t want too much of it,” says Blake, echoing challenges that are faced in other industries like fashion. “It’s a delicate balance of inventory control.”

Today, Lichen is comfortable as a midsize company. The founders have partnered with a freight carrier to ship furniture internationally, but they don’t have to rely on distributors or fulfillment centers because they’re not interested in scaling to that level. “We’re medium speed right now,” Blake says.

THE POWER OF SMALL

Chiriac’s journey might have been different if he’d tried to capture a smaller market before shooting for international distribution. It probably didn’t help that he didn’t have the cool factor of a Brooklyn brand, or marketing knowledge, or the budget to stand out in an overly saturated market. As Dillon Jones, who runs a Minnesota-based digital marketing agency called Johnson Jones Group, points out, marketing furniture is particularly difficult because it’s not something that people search for as often as, say, a plumber. “When somebody isn’t seeking out innovation, it needs to be put in front of them; that’s where targeting is hard,” he says.

When considered against the backdrop of Salone del Mobile, where designers unveil extravagant couches created for a select number of monied clients, Chiriac’s story is a reminder of the politics of power at play, and how pervasive gatekeeping continues to be in the design industry. It’s also a reminder that it’s hard to innovate in a risk-averse industry that can seem to care more about good logistics than good design.

The problem with Chiriac’s sofa may be that it ended up falling between two stools. It’s not a fit for the high end of the market, which boasts good design but small distribution; nor is it a fit for the trend-hungry consumer furniture industry, which needs validation before going to market. As Blake puts it: “So much of the furniture industry is a monopoly game of distribution and export.”

WHEN NOVELTY DOESN’T WIN

It’s possible that Chiriac created something that seems smart and practical but isn’t necessarily desirable. In a self-reinforcing market where companies tend to cash in on trends by simply churning out more of the same products, his story shows just how hard it is to break through—even with a utility patent in hand.

Chiriac fought hard to get that patent; he says he felt unprotected as an individual inventor pitching his idea to big companies. “There are thousands and thousands of other sofas, shapes, materials, colors, that all compete in the same space,” he wrote. “If I have something that I’m the only one selling, I have better chances.”

That may be true, but it’s important to note that a patent is not a golden ticket to a successful business. “This idea of patents as a signal of approval is important but it doesn’t mean what people think it means,” says Sarah Burstein, an expert in design patents and a professor of law at the Suffolk University Law School.

To qualify for a utility patent in the eyes of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), an invention has to be new or, as Burstein puts it, “new enough.” And it has to be useful. The USPTO does not take into consideration whether consumers actually want it, whether it would make for a viable business, or even whether it’s a good product. “People get confused and they think a patent means it’s effective or it works well, and it doesn’t mean any of those things,” Burstein says. “It just means the statutory requirements have been met.” She notes that, for better or worse, a patent does have signaling power for investors.

Ultimately, everyone has their own definition of innovation. For some, it’s about a more sustainable material or a different manufacturing process. For Chiriac, it’s about a mechanism that could help you reclaim half of your living room. For Lichen’s cofounders, it’s about pushing the narrative beyond familiar tropes like “timeless design” or even “mid-century design.”

When I point out the irony that Chiriac has spent a decade trying to launch his Shrinkable Sofa, while every single year famous designers and furniture brands launch a new sofa that looks like a version of last year’s sofa, Blake’s response says it all: “Of course it’s going to look like last year’s sofa—you got last year’s designer. What did you think was going to happen?”