- | 8:00 am

The sci-fi motor design that could help save the EV industry

The donut-shaped wheel might just power your next electric vehicle.

The dream of an all-electric world in which every bike, car, and truck silently cruises on roads of happiness and joy is in trouble. From really bad environmental and social issues to slow adoption and President Donald Trump’s recent ban on subsidies, things look grim for EVs. The only thing that keeps going forward is innovation (well, mostly), as companies continue coming up with some really great ideas to fulfill the EV promise. One of them is a Finnish company that has designed something brilliant called the Donut.

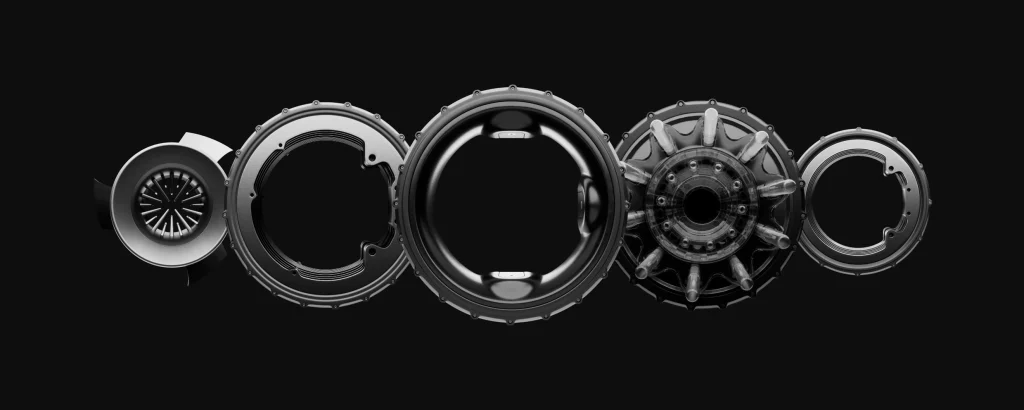

Donut Labs, which unveiled a family of in-wheel electric motors at CES 2025, has spent almost a decade searching for one of the holy grails of the EV industry: in-wheel motors that actually work. These motors aim to outperform current individual-wheel drive (IWD) systems, which are widely used in today’s EVs, while also surpassing competing in-wheel motor technologies that are still in the prototype stage.

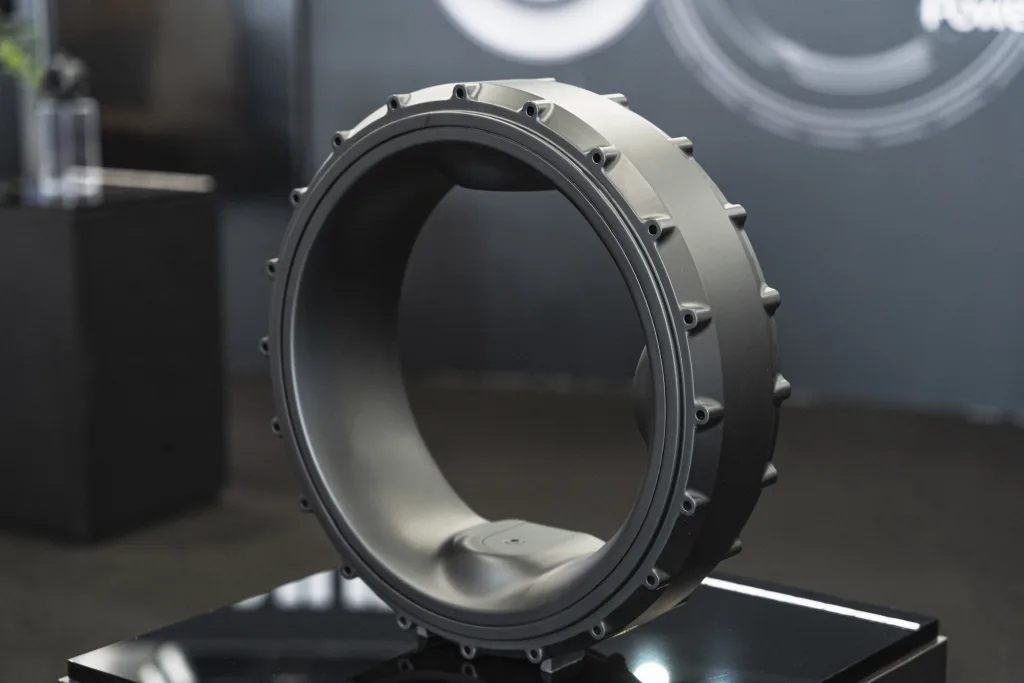

Donut Labs’s curious design—which looks like an empty metal cylinder with tapered edges—could mark a pivotal moment for EV propulsion systems, with huge implications for vehicle performance, cost, and design flexibility.

Current electric vehicles predominantly rely on IWD systems, where each wheel is powered by its own independent motor. Unlike traditional internal combustion engine vehicles that use a central drivetrain, IWD systems employ inboard motors connected to wheels via half shafts. This design allows for features like torque vectoring—adjusting torque at each wheel for better handling—and tank turning, where wheels on opposite sides rotate in reverse to pivot the vehicle on the spot.

The in-wheel motors like the ones that Donut Labs has created, also known as hub motors, aim to eliminate these components by integrating the motor directly into the wheel hub. There is no transmission. No extra pieces. The motor directly drives the wheel inside the wheel. By doing so, hub motors simplify vehicle architecture and reduce drivetrain losses.

Yet adoption of hub motors has been slow due to technical challenges and concerns about unsprung mass—the weight of components directly connected to the wheels—affecting ride quality. There are also questions about long-term durability. These have limited their application in EVs, leaving most efforts in the prototype phase due to cost and poor performance. Until now.

A sci-fi fantasy come true

Donut Labs has been developing Donut motors for nearly seven years, “starting with the idea of rethinking what propulsion systems and whole system architectures could look like in different kinds of vehicles if there was a high performance and low mass in-wheel motor available,” CEO Marko Lehtimäki tells me in an interview.

He says his team looked at all existing electric motor designs, analyzed their potential, and found that not a single motor in the world met the performance and feature set they wanted to achieve, especially when it came to reducing mass to a level suitable for in-wheel motor use. This inspired them to start from scratch and imagine a new type of motor, optimized for performance, weight, and cost.

Lehtimäki says that the Donut Labs team went through several design generations and endless smaller iterations combining different winding techniques and magnet configurations before identifying the right ways to provide the highest performance while using common and inexpensive materials. “Our Donut motor is a solution that no longer requires compromises,” Lehtimäki tells me. “We’ve managed to bring something new to operators in the field that has previously not been possible.”

Now on the road

The car motors introduced at CES are ready to go into production, but still not in any vehicle. Their in-wheel technology is already on the road, like Donut engines used on the Verge TS Pro bike, by Verge Motorcycles.

“The feedback has been overwhelmingly positive,” Lehtimäki says. “Many riders initially worry they’ll miss the roar of a traditional engine, but after just a few minutes on our electric bike, they discover that the near-silent torque is every bit as thrilling, if not more, than engine noise.” It’s like a Tron Lightcycle fantasy, without the laser mayhem behind.

The motors used in the Verge bike are just the first of a modular platform that includes battery modules, software, and control systems designed to work seamlessly together in the wheel, adaptable to every vehicle imaginable.

The platform allows manufacturers to assemble vehicles faster and more efficiently by choosing from a catalog of interoperable components. Lehtimäki explains that traditional vehicle development involves extensive integration work with components sourced from various suppliers. “Our solution enables all parts to function without any trouble, accelerating the development effort and opening new opportunities in many fields of industry,” he says. And the architecture Donut Labs has designed allows the company to produce motors for all kinds of vehicles, from sports bikes to cars to buses to commercial trucks.

Unheard power

According to the company’s numbers, its in-wheel motors stand out due to their performance metrics. The flagship 21-inch motor for cars delivers 4,300 newton meters (Nm) of torque and 630 kilowatts (kW) of power, while weighing just 88 pounds (not quite 40 kilograms). Pound by pound, those stats are unheard of in the current in-wheel motor prototypes and in the current EV and industrial combustion engine car industry. For comparison, Protean Electric’s Pd18 in-wheel motor generates 1,250 Nm of torque and 80 kW of power, with a similar weight of 36 kilos.

Ville Piippo, chief product officer at Donut Labs, says that it was very hard to design a motor with this level of performance using regular materials, which is key to keeping the cost low (the company hasn’t disclosed the price of its engines). “A lot of people think that one can only get these kinds of crazy performance specs by going exotic in material selection, but this is not the case,” Piippo tells me.

The Donut engines use standard magnets, steel laminations, and winding materials, but Piippo says “by combining multiple big innovations and a whole lot of smaller ideas, we created in-wheel motors that have both the highest torque density and the highest power density of any electric motor in the world.”

The result is an electric motor with a peak efficiency of over 97%, again an unheard figure in the industry. “The real beauty is in the way we can optimize the efficiency map to have high efficiency in the area of revolution per minute and load where it’s needed in a specific application,” Piippo says. This means the motor can deliver maximum energy transfer, from the battery to motion, with minimal losses to match the load and speed requirements, translating to greater range and lower energy consumption.

The key to all of this, Piippo says, is the Donut. “The most significant innovation lies in our motor’s unique shape. By using a larger diameter with minimal active materials, we’re able to achieve higher torque and power density, essentially delivering more power and torque per kilogram than conventional motors.”

The unsprung mass problem

Historically, unsprung mass has been a major obstacle for in-wheel motors. This is an important parameter in handling, or how a vehicle feels like to drive. All mass that is in direct contact with the road without going through suspension is unsprung mass: a wheel’s tires, in-wheel motors, brake rotor, control arms, steering arms, etc. “Generally speaking, less unsprung mass is most often better than more unsprung mass,” Piipo explains, “but it is just one parameter among others, so one should not overstate its importance over other parameters.”

A more important metric is the ratio of unsprung mass to total vehicle mass, he says. Adding a lot of unsprung mass in a very lightweight vehicle can have negative effects, but adding a small amount of unsprung mass to an already heavy vehicle will have little to no effect. “The relative weight of the Donut motor is so small that, for the first time, the unsprung mass is insignificant,” Lehtimäki explains.

At the same time, the company claims its in-wheel design’s positive effects are impressive. These include precision in traction control, reduced system complexity, and improved overall vehicle performance. By integrating the motor directly into the wheel, Donut Labs says the need for components like drive shafts and gearboxes is eliminated, reducing weight and simplifying assembly, thus greatly reducing the cost of the overall car.

Driving ahead

In-wheel motors from other manufacturers have made strides but fall short of Donut Labs’s achievements. ProteanDrive, for example (which has Bentley behind it) integrates inverters within the wheel hub but lacks the torque and power density of Donut motors. The Elaphe L1500 targets SUVs and trucks but doesn’t match Donut’s performance metrics either. DeepDrive’s dual-rotor design promises material efficiency and range improvements but remains in the lab.

In contrast, Donut motors are already in production. The company’s motorcycle motors, used in the Verge TS Pro, deliver 150 kW of power and 1,200 Nm of torque at a weight of just 21 kilograms.

Perhaps that’s why, after the car motor introduction at CES, that the interest from the automotive industry has been extremely strong, according to Lehtimäki, who says, “We are in serious discussions with hundreds of potential partners.” (He doesn’t reveal any names due to the nature of negotiations.) The company’s design performance and the scalable motor lineup, which includes designs for trucks, two-wheelers, and drones, is key.

But the biggest point may be the cost. Reducing manufacturing costs through the use of common materials and eliminating drivetrain components, the Donut Labs design allows for more affordable EV production. Lehtimäki says that this is the first electric motor that truly responds to the current requirements of electric vehicles and opens doors to completely new types of solutions. And in these times of EV crisis, these may be the definitive selling point of the technology.