- | 7:00 am

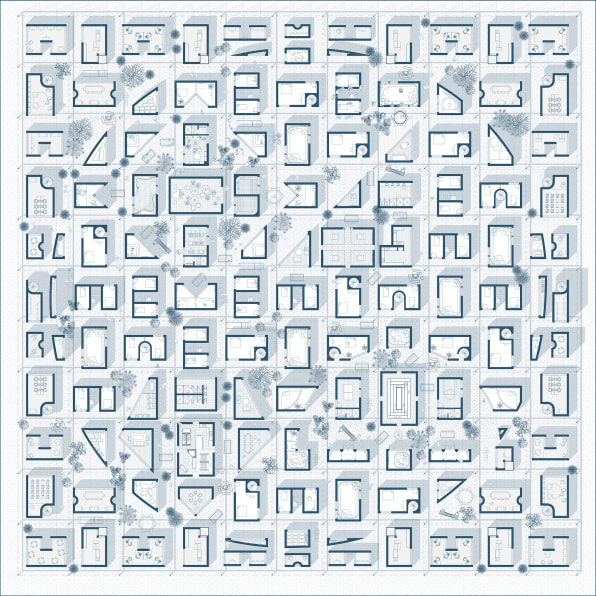

The takeaways from 35 co-living projects were distilled into these experimental designs

It’s no secret that the U.S. has been marred by a housing crisis for decades. In the face of the housing shortage, architects have proposed higher density, modular construction, and even shipping container apartment complexes. Now, a new exhibition in San Francisco explores the potential for one of humanity’s oldest forms of living to ease the country’s housing crisis: cohabitating.

[Photo: The Open Workshop]

Titled “House of Commons,” the exhibition presents more than 35 examples from the Bay Area but also Baltimore; Berlin; Seoul; and Saint-Cloud, France. These case studies informed the design of five new proposals representing a range of flexible strategies to support social interaction and varying levels of privacy.In San Francisco, the research has already been used to inform new policy around the definition of group housing, which was being exploited by developers and will now mandate a minimum of 33% shared spaces. The proposals, however, offer myriad approaches and layouts that can be used to inform co-living design in other cities as well.

The exhibition is on view now at the David Ireland House in San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood. It was developed by local architecture firm the Open Workshop, based on research done by the firm’s founding principal, Neeraj Bhatia, and Antje Steinmuller, an associate professor at California College of Art.

When Bhatia moved to the Bay Area in 2013, he was immediately faced with the city’s housing crisis and became interested in how different living arrangements could allow people to have control over their lives. “I value my privacy and my solitude, and what I found through looking at various case studies is that there is a range of ways that people live together, and many of them embrace privacy as much as they do coming together,” he says.

[Photo: The Open Workshop]

CO-LIVING AROUND THE WORLD

The exhibition is the culmination of five years of research into communities like R50, a six-story co-living project in Berlin, and the Jystrup Sawmill in rural Denmark, an L-shaped complex of townhouses connected by internal streets. One of the earliest examples that the team analyzed dates back to the 1960s, when the 80-acre Black Bear Ranch was born in Siskiyou County, California. Around that time, Bhatia says, about 1 million people in America were living in communes.

“In the 1960s, there was . . . an emphasis on shared ownership, raising kids together, sharing labor,” he says. Today, the motivations are much broader: Some people do it to bring down costs, others seek a community of like-minded people who share their lifestyle, values, and politics.

Many co-living developments are built in preexisting structures, like Chaortica, which is part of an intentional community network in San Francisco located in a century-old single-family residence with a garden and a greenhouse. Others, like the 18-story Starcity co-living startup in downtown San Jose, California, built their own buildings. Bathia says that the Starcity development is geared more toward short-term stays for residents who are new to the city and want to meet new people while saving money.

[Photo: The Open Workshop]

CO-LIVING IN THE FUTURE

Drawing lessons from all the examples the team studied, Bhatia created five speculative co-living designs. Each city has a unique set of cultures and challenges, so the architect eschewed context-specific proposals, but he says the different schemes relate to different densities, making them suitable for both urban and suburban environments.

“Grids,” for example, offers the most private scenario. It envisions a community organized around an urban grid, except in this version the streets are replaced with housing and the central blocks form courtyards, gardens, and shared spaces. Here, Bhatia was inspired by the idea of a “collective outdoor room,” much like the constellation of internal courtyards in Barcelona’s Eixample district.

On the other end of the spectrum, the “Surface” scheme portrays an extreme example of people living together with very few walls, and boundaries defined primarily through curtains and movable furniture. “The idea that walls are the sole mechanism to define these territories is eradicated,” Bhatia says. “This would be a scheme for those who are more willing to live together.”

[Photo: The Open Workshop]

The easiest way to implement any of these proposals would be to build them from scratch, but Bhatia could envision them fitting into existing buildings as well. The linear layout of “Grids” could lend itself well to former single-room-occupancy buildings—where tenants rent out a room and share amenities like kitchens and bathrooms—or hotels, which already come with long corridors flanked by rooms.And “Surface,” which requires an open space that can be subdivided as needed, can be well suited to converted warehouses. “It’s about thinking about paths of least resistance and where development might get you more for less,” Bhatia says. “How do we produce something simple that can offer huge amounts of complexity?”