- | 9:00 am

The world is on fire. Can design help save it?

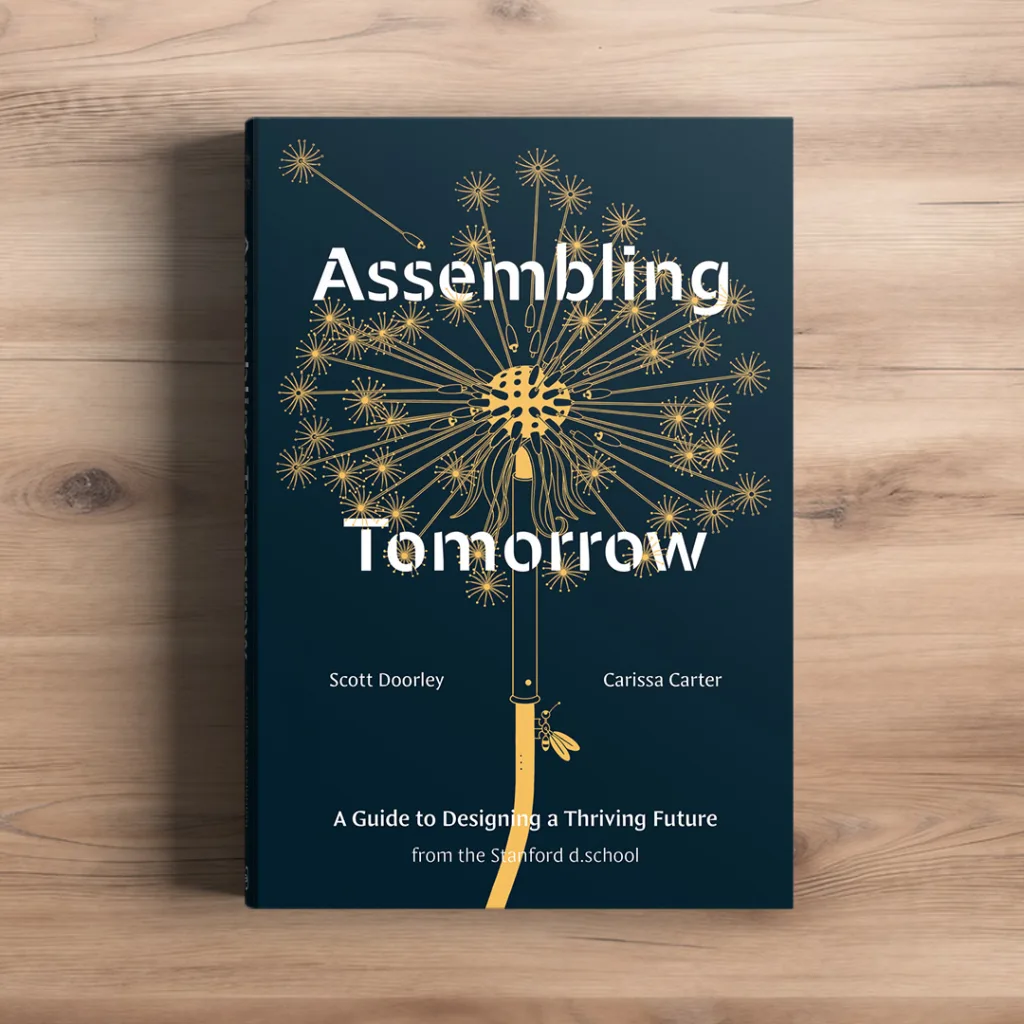

A new book from Stanford design school leaders explores the radical potential of design to reshape our world for the better.

“In an environment that is screwed up visually, physically, and chemically, the best and simplest thing that architects, industrial designers, planners, etc., could do for humanity would be to stop working entirely,” wrote designer and educator Victor Papanek in his 1971 book, Design for The Real World. Fifty years later, there’s still a truth in Papanek’s critique that rings true to me. In this moment when it seems every system is collapsing in on itself—the rise of artificial intelligence, the instability of democracies, the ever-present climate crisis—the role of the designer can feel uncertain.

I was thinking about Papanek’s line while reading the new book, Assembling Tomorrow: A Guide to Designing a Thriving Future by Scott Doorley and Carissa Carter, out now from TenSpeed Press. Carter and Doorley, the academic director and creative director, respectively, at Stanford’s d.school, are much more optimistic than Papanek about design’s role in creating a future that looks better than the present.

Divided into two parts, “Intangibles” and “Actionables,” Carter and Doorley write about what they call “runaway design,” or the feeling that the systems we’ve made are out of our control and what we can do to reshape them. Interspersed throughout are a series of short fictional stories—dispatches from the future—that bring the often abstract ideas back down to reality.

I’ll admit to being skeptical of an overly optimistic view of design. On my worst days I’m more Papanek than Stanford’s d.school, but what Doorley and Carter are doing in the book is not blind optimism; rather, it’s a reclaiming of design as a future-oriented practice, available to everyone. In this moment when design can feel like a tool for profit, for markets, for power, Assembling Tomorrow paints design as a tool for everyone who is interested in building better futures and how to use that tool with care, inclusion, and rigor.

To design in this moment, they write, requires you “reconsider how you measure success, remove what’s not working, reorient yourself, and remake the way you do things.” I was interested in speaking with them about their optimism for design, where the design professions go next, and how we take back the reins of runaway design. Our conversation was edited for clarity.

How do you define design?

Scott Doorley: I like to use the metaphor of a solid, a liquid, and a gas. Design started off as a solid, where it’s about making things that act in the world. Then it moved into a liquid, which is more about how we design experiences and services. Design is not just the thing, but it’s the stuff around it. Right now, it feels like design is turning into this gas, where it really is everything, you know? It’s not just the thing, the services, the experience, but also the impacts and the systems. What design has been asked to do has expanded over time.

I think the difference between design and other disciplines of making is that design is about desirability. It’s about finding what you care about, and then embodying that in the world. And that’s a really specific way to go about doing things. I think it’s a helpful way, but it can also be harmful.

Carissa Carter: When we talk about design, we think of it on many levels and layers. If I pick up my phone, for example, it is a physical object that was designed—somebody decided on the radius of the corners and the materials to manufacture it. But it’s not just a physical object, it’s also a digital object; each app was designed, too. There were wireframes to determine the flow, there was graphic design work on the icons and the interface. Each of these enables any number of experiences to happen. I can have this video call with somebody like you on the other side of the country; somebody designed how this interaction can take place so there is also an experience layer. These products and experiences, then, live within any number of systems that exist in the world. I have a phone plan that decides where in this country I get access to that phone system. If I want a new app, I go to an app store which has its own rules for how people can contribute and what we can download. Then, nested within everything, there’s the technology that powers all of that, including emerging technologies like machine learning algorithms that learn from us. What was included in the data? How it learns is a design decision.

So, design is data, tech, product, experience, and system. All of those layers have implications, both positive and negative, both near term and long term. There are apps on my phone right now that have allowed people to come together and assist in being a voice for change, and those same apps have also enabled school bullying and declining mental health in our youth. That’s all design work. We think of design individually as each of those layers, but also that full stack.

Your book is called Assembling Tomorrow: A Guide to Designing a Thriving Future. If design is everything, who is this book for? If everything is designed and everyone is designing, is this book for everyone?

Carter: This book wasn’t written only for designers, but we certainly feel like it speaks to them. It’s really for people who care about their impact on the world and are paying attention to what they’re interacting with. In the same way that a parent designs the arc of where their children are going to be over the course of the day—who’s picking up the carpool, what house are they going to be going to—they’re making decisions about the experience that their kid is going to have. That’s important because it’s a moment in their day that means something. This book is for anybody that cares about things like that, from people that are designing the meetings at their workplace so that everybody has a voice and can participate, to the people that want to figure out a new policy on how to run their town.

Doorley: I think the things that we do and make shape the world, in large and small ways. That can be anybody, from leaders to parents to teachers, a lot of us are shaping the future more than we know. We wanted to acknowledge that and then figure out how we can do that better. How can you do it in a way that’s more thoughtful?

One of the central ideas in the book is this term you call “runaway design.” Can you talk about what runaway design means?

Carter: Think about a runaway train flying down the tracks, impossible to stop. It could crash into something and cause some kind of harm. We think of runaway design similar to that, except, imagine that we can’t see that train. We can feel that something’s happening, but it feels wild and a little bit out of control. That feeling is coming primarily from the emerging technologies, like AI and synthetic biology, that are coming at us from all angles. The natural world is responding in a big way, and our human effects on the changing climate are adding up. It feels like a fraught moment in the world. We call it “runaway design” because it is our design decisions, as humans, that have brought this to fruition. We want to both acknowledge why it is feeling so fraught, and also talk about what might we all do about it.

Doorley: We’re trying to call attention to this moment where the materials that we’re making with are fundamentally different from materials we’ve worked with in the past: they can change after we’ve made them. AI can literally make decisions; it can alter itself. Synthetic biology can grow and evolve and spread, hence the runaway moniker.

As I was reading the book, I was really curious about why you called this runaway design, emphasis on the design part. How much of this unease we are feeling is from forces that we might traditionally think of as outside of design: globalization, economic forces, changing demographics? Talk to me about that intersection between the things we make and the cultural, political, and economic forces that are shaping how we make things?

Doorley: I’m so glad you asked this question. When you think of design, the original definition of design is planning, basically, which sounds like it’s about things that you have control over. But a lot of design practice is about working with the world, right? Prototyping is putting something out there to see what happens. Even researching human factors and stuff like that is trying to figure out what’s going on in the world that I need to respond to. So much of design, in particular, is not about controlling those systems but about trying to interface with those systems. So, for example, once the technology takes off, are we even designing it anymore or is it doing its own thing? I think we have to acknowledge that we have to still be in that conversation as it runs away. We have to jump on the train, we have to pull the brakes, we have to switch tracks, whatever it is. I think it’s a very tricky thing, but I think design has always been about dealing with the things that are outside of your control and trying to be in front of them.

Carter: I think part of the runaway comes from the fact that it’s hard to pull them apart. I would say that those systems you are talking about are human-made, too. They were designed. But it also is a moment where I think as individuals, we can feel powerless. Sometimes it’s overwhelming. Part of what we want to do is acknowledge that it’s okay to feel overwhelmed.

That powerlessness that you’re talking about really resonates with me. Perhaps this says more about me, but I was struck by the optimism in the book. Yet I was reading it and felt that powerlessness. These runaways are so big, what does any one person do?

In the last chapter, you mention market forces and how they influence design, but you don’t really ever talk about profit. You don’t really talk about capitalism. You don’t really talk about democracy. You don’t really talk about these big systems much. I’m wondering how you think about that exchange between the individual person, or the individual designer, and the biggest of the design systems that have caused a lot of this runaway. How do we, as individuals, negotiate the power that we do have within those systems?

Carter: That’s a great question. We tend to start from a place of personal agency, just crossing that hurdle of feeling, “Oh, I can start. I can take some action.” We’re gonna need that change from the high level, but we need it from the bottom at the same time.

Doorley: On the other side, there’s a world in which a lot of people are creating a lot of things with very good intentions and, even with those good intentions, things seem to go awry to some degree. So, we’re interested in what it is about the way people approach problems that creates these blindspots that end up being difficult in the long run. Even when you’re trying, even when the things are in place that will make it go well, why does it not always go well?

Let’s get specific here. The second half of the book is a series of what you call “actionables”—things like “be awkward,” “shapeshift,” “disorient yourself.” Those don’t immediately feel actionable to me. What does it mean to be awkward, what does it mean to shapeshift, when you are moving through your day, working at your job, within these systems that are constantly encouraging the opposite?

Carter: Those actionable are about seeing the unseen, or seeing the things that we take for granted and lay in our peripheral vision. You mentioned one: being awkward. We’ve all had that feeling of not fitting in. Instead of trying to mitigate that awkwardness immediately, how can you stop for a second to notice that? Why do you feel that? When does it happen? Is it because the people all around me have something in common and I don’t? What might bridge that? What do I notice about how they’re behaving? What are their norms? It’s about paying attention to those tiny moments that you either feel within yourself or you notice in others.

Doorley: It’s about being able to see the things that you miss because there are opportunities in the gaps. The people who are making change are noticing those gaps, they’re noticing things that aren’t working but they’re willing to stick with that long enough to make a change. You can’t see the change unless you feel the awkwardness and unless you are a little disoriented, otherwise you’re just moving through life as it is.

I want to zoom out and talk about the design fields themselves. How do the design fields need to change—at the professional level, at the discipline level, at that structural level—to start to make these changes that you write about in the book?

Carter: If we want the technology, the products, etc, of the future to represent all of us, they have to be created by all of us. The future technologies, especially, are being created by a small group of people. Designers are still slightly on the sidelines. In a perfect world, I would erase how technology started and designers would be at the forefront of that from the get-go because we are the translators. We’re the ones that can talk to everyone—the technologists and the historians and the humanists—and make sure everyone is in the room.

This connects to the end of the book where you talk about “design for healing.” What I like about that word is that healing is not innovative. Healing is repair. Healing is going back to what something was and trying to make it better again. How can we reframe design to think of it not always as innovation but also as healing?

Carter: Design for healing means that everything we put into the world—the small and the large—is going to affect something else. So even if your widget, even if your system, even if your policy works as intended, if it doesn’t break, it’s still going to break something else, somewhere along the line, either near term or long term. To design for healing is to take care with what you’ve put out into the world and watch for its effects. We have to get better at predicting all of those potential places where things could go wrong from the get go and taking responsibility and shepherding that work into the future.

Doorley: From our standpoint, this is already happening and we wanted to identity and celebrate that in the book. We write about the architect Francis Kere, who’s a Pritzker Prize winning architect. He uses materials that are available locally and when he builds, say, a school or a hospital, he brings everybody in to build it together. So not only is he leaving a nice structure behind, which used to be what architecture was, he’s also creating a framework where they can do it again. The community can be empowered to do it themselves.

What we hope to do with this book is have a mindset shift around the purpose of what we do. Is the purpose the finished product? Is the purpose the ability to create? The act of building? Or is the purpose the healing that can happen in a community when you get together and make something? What you create down the road is almost more important than what you create in the moment.