- | 7:00 am

This feminist suit makes eye contact with the men gazing at it

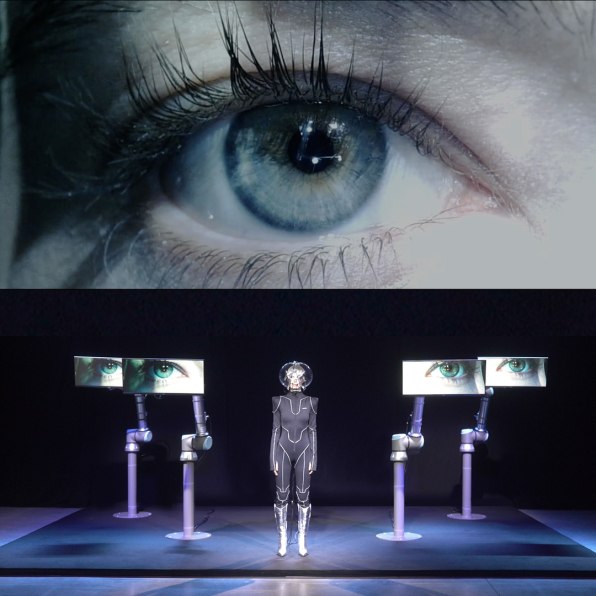

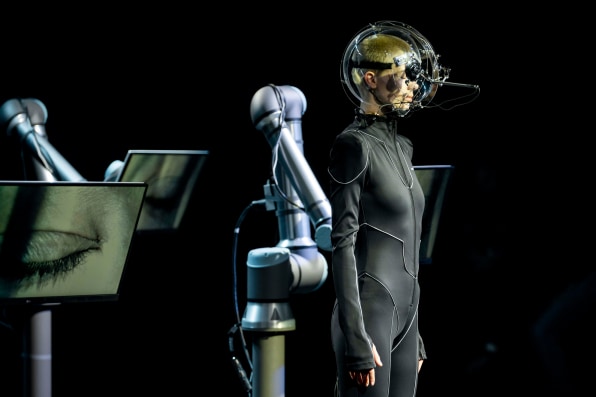

The suit looks like it’s meant for exploring space, or maybe the deep ocean. From the outfit’s neoprene-like sheen, to its bulbous fishbowl helmet, the entire garment feels designed to keep malicious environmental forces out. But in fact, it is a rebuke, aimed at anyone looking in. And its four imposing robot arms are here to remind you of that.

This is Returning the Gaze, the latest project by the Iranian-American artist Behnaz Farahi. Created at the invitation of the fashion label ANNAKIKI for its cyborg-themed Milan show last month, Returning the Gaze uses two cameras to track its wearer’s eyes. Then those eyes appear supersized on four screens held by Universal Robots robotic appendages. The entire suit is built for a model to stare back, powerfully, at her gawkers.

[Photo: courtesy Behnaz Farahi]

“Models are always walking on stage, with viewers looking at the models. The notion of gaze and staring are so dominant in this process,” says Farahi. “I wanted this project to address and challenge the logic of a runway show.”

In the past, Farahi has designed a furry coat that bristles like a porcupine when looked at. She’s created a pair of niqābs that blink a secret, Morse-code-like language to communicate past eavesdroppers. Her work is largely inspired by film theorist Laura Mulvey’s landmark essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema [pdf], which outlines the impact of the male gaze. As Mulvey argues, the male gaze is not merely an uncomfortable but fleeting sensation of being checked out against your will; it’s an inescapable, omnipresent point of view that’s shaped our culture. Nearly 50 years since this essay was written, we can see how from fashion to architecture, this exploitative male perspective has largely designed the world in which we live. Because of this history, even when a woman looks at herself alone in the mirror, the male gaze can still lurk like an invisible shadow.

[Photo: courtesy Behnaz Farahi]

“I’m really amazed by this notion of gaze, and Laura Mulvey’s work,” says Farahi. But in recent years, she’s been attracted to another concept: surveillance feminism, or the idea of cameras and other tools that are often used to excerpt the male gaze could be augmented for female empowerment. “Surveillance usually has a bad connotation,” she says, “but how you use surveillance as a feminist act? I’m super interested in it.”

[Photo: courtesy Behnaz Farahi]

Now, don’t take Farahi’s criticism the wrong way. She is not oversimplifying men into a community of leering misfits or arguing that someone should never look upon someone else with desire. She acknowledges there are times a gaze is invited—ranging from social media posts to runway shows—and still finds herself fascinated by the important role of glances and eye contact in communication. These are not ideas she’s ignoring by challenging the male gaze on a fashion runway. Rather, she’s trying to call attention to these concepts, and drive people to deconstruct their nuance.

“You already have this logic of the gaze, inviting it in when you’re a model walking on the catwalk. Having said that, we hear a lot of stories in the fashion world of how women are constantly victims of unwanted sexual attention backstage, during it, or after the shows,” says Farahi. “[I] don’t necessarily want everyone to feel absolutely uncomfortable and not look, but to start having conversations about the notion of the gaze. Historically, people are not aware how they look [at someone else]. Sometimes, gaze can be obtrusive, and sometimes it can be more inviting.”