- | 9:30 am

This off-grid toilet uses sand and a conveyor belt to ‘flush’ your business

Developed by a recent graduate, the toilet doesn’t require water or electricity, and was designed to be used in rural areas.

You may not think about this when you do your morning business, but over 1.7 billion people still don’t have basic sanitation services, such as private toilets or communal latrines. Almost 500 million people still practice open defecation (yes, that’s pooping out in the open), 92% of whom live in rural areas.

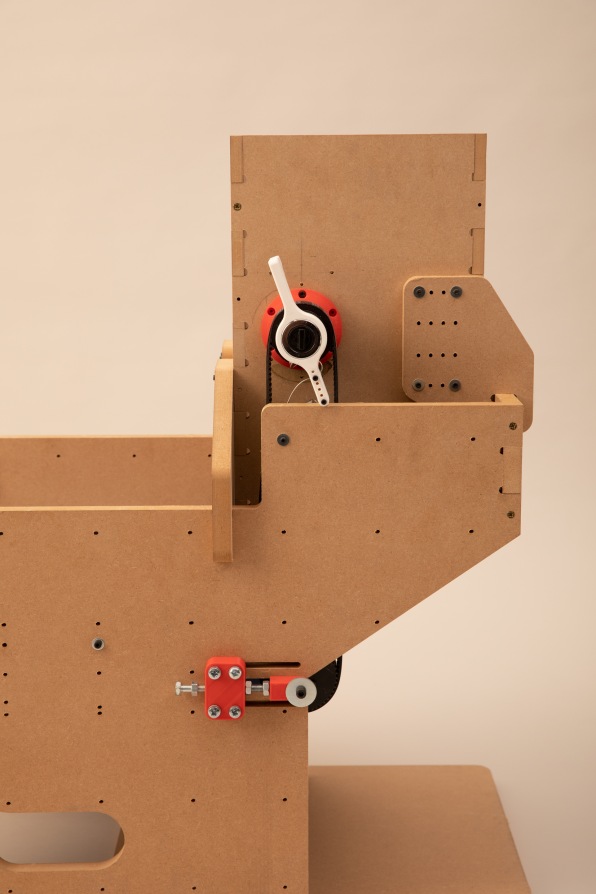

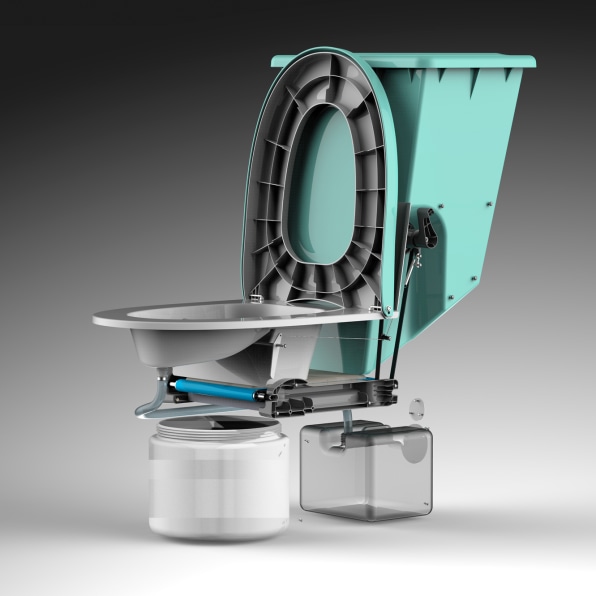

That’s why Archie Read, a recent graduate from London’s Brunel University, designed Sandi. The toilet uses a mechanical flush (no electricity), a basic conveyor belt to move the solids away (no water), and a divider inside the bowl that separates the waste streams so they can be used as independent fertilizers. For now, Sandi is just a concept with an accompanying prototype, but if it makes it on the market, it could operate off-grid, making it a viable—and dignified—solution for rural families with no water, septic tanks, or sewage systems.

Read, who received a degree in product design engineering, came up with the idea during a recent internship in Madagascar. He was working for toilet company LooWatt, which captures waste in a biodegradable polymer film but requires regular servicing. “It’s a great product, but like every other sustainable toilet designed, they’re targeting cities,” says Read.

Sandi joins a growing ecosystem of off-grid toilets that run the gamut from something that looks like a potty training toilet and comes with a biodegradable single-use bag, to a glorified bucket with a lid, to a high-tech toilet that uses nanotechnology to convert human waste to clean water and ash without using any energy. Like Sandi, these toilets don’t need water to function, but most of them (except for the last one) don’t flush at all, which Read describes as “safe but not a nice experience.”

This is where Sandi comes in. The toilet bowl has two separate compartments: one guides urine into a container below; the other has a simple conveyor belt, which is covered with a thin layer of sand that renews with every flush. Read opted for sand because it prevents the feces from sticking to the conveyor belt, but he says sawdust or dirt would work equally well. (Testing the prototype involved instant mashed potato mixed with various amounts of water.)

When you’re done, you press the flush handle, which rotates the conveyor belt away from view and drops your business into a separate container below. For a household of 7, he says the liquid container would need to be emptied every two days, while the solid container would need to be emptied after four. After that, people can immediately use the urine as fertilizer, and bury the rest to use as compost four weeks later.The key here is that the whole operation is low-tech by design. “If you have a nice complex electrical component, and you’re in a village that’s 50 miles away from any technician who can fix it, you can’t expect them to travel 50 miles there and 50 miles back to fix one toilet,” says Read. “It has to be in a situation that’s fixable by 90% of people themselves.”

It’s too soon to talk logistics, but for now, Reed has priced the product at $74 per unit, which puts it somewhere in the middle of his competition. Eventually, he envisions working with NGOs that could buy or rent the toilets and educate people about safe sanitation in the process. “If your main priority is safety, you can’t charge people a fortune for it,” he says. “It’s not like you’re selling a luxury product.”