- | 8:00 am

Want to make a creative breakthrough? Leave your desk

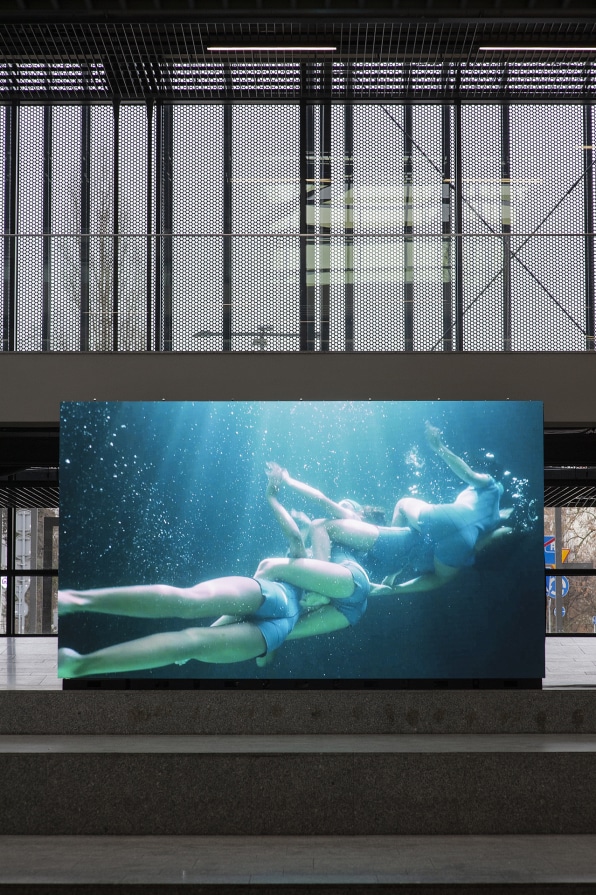

Artist Miriam Simun on the power of experiential learning.

Miriam Simun is an artist, interaction designer, and educator investigating the implications of socio-technical and environmental change at the intersection of ecology, technology, and the body.

Simun’s work demonstrates the importance of embodied experience—not only to better understand human behavior, but also to adapt one’s perception and creative techniques for complex challenges like climate change or automation. In this interview, she shares how she modifies her research and creative practice (and even modifies her own senses) in order to gain new perspective or convey novel insights through her work.

Fast Company: When did you first realize you had an interest in design?

Miriam Simun: My grandfather was a sculptor, so I was always around him making things. And as a kid I was always making things myself. Then, in university, I studied the sociology of technology, and my first job after university was at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. I was researching how technology affects society—mainly how children and young people were using technology. The research was meant to lead to policy recommendations—to govern technological design and deployment. It was in doing this research that I understood how much it is really in the design of systems that the social realities they facilitate get laid down.

FC: How did you move from sociology to design?

MS: A large part of my work at the Berkman Center was looking at how young people were using social media. This was 2008. MySpace was still around, and Facebook had just started a few years earlier. So I did a lot of interviews with young people. I was also a young person at the time, but I was 21 and talking to 12- and 13-year-olds, who were making friends and hanging out with their friends primarily through social media. It’s normal now, but then it was still pretty surprising.

They were learning how to be friends and how to relate to people through these technology platforms. And these technologies were not designed to facilitate the building of human bonds; they were designed, ultimately, to sell advertising. And so I understood rather suddenly and dramatically, the design of these systems were shaping how all of these people were forming their first relations in the world. And that drew me a little out of academia, and into making things and seeing how making things can affect the world.

FC: What drew you to the unique intersection of ecology, technology, and the body, and how are you exploring that intersection through your practices?

MS: When I studied sociology, we learned how to conduct research, how to listen to people and spend time with them and try to understand their point of view and their reality; and through this, to understand something about the world. That’s still, to this day, the core of my research process, no matter what the project is. So I value what happens when I go out into the world with my body and spend time being inside of what I’m trying to understand. That’s when you begin to get at the complexities—the contradiction inherent in things.

The second part I have understood more and more over the years is the embodied piece of learning about the world. Take a recent work, Transhumanist Cephalopod Evolution. This is a psycho-physical training regimen to evolve the future of the human based on the role-model-species of a cephalopod (octopus, squid, cuttlefish, nautilus). We train within our existing bioavailabilities (no implants or prosthetics) three cephalopodic traits: tactile intelligence, shapeshifting ability, and distributed intelligence.

But how did I get there? I was interested in human response to sea-level rise. But, I was interested in flipping the script from building a seawall—managing the environment to fit our needs—to thinking about how we might modify ourselves to accommodate and adapt to a changing climate. And I read a lot, and spoke with many geneticists, roboticists, engineers, biologists. And after my brain was full of information, I wasn’t sure where to go next.

So I decided to learn how to free dive; dive deep underwater with no scuba gear, something that I would not be naturally inclined to do, but the research required it. On the first day, I went from being able to hold my breath for 20 seconds to 2-and-a-half minutes. I was utterly amazed at what my body was capable of. And so I began to wonder, what other bioavailabilities exist within this body I’m walking around in that I might not even know about? This question could only arise through this kind of lived, embodied research process.

Over the years, I’ve understood that being “in the field”—smelling endangered flowers (or rather not smelling them) or learning to hunt animals or learning to free dive—this bodily knowledge is imperative to understanding, especially when it comes to ecological relations.

FC: Your work uses a variety of media like video, performance, sculptural objects, and sensory experiences. How do you decide which media fit the narratives you want to tell?

MS: The best medium for the work becomes apparent during the research process. I’m an experiential learner. I figure out my position, and what I think, through editing video, or writing, or composing a scent, or drawing. It becomes clear in the process that this is the medium that best conveys what I’ve felt or learned, or the questions I have, or the sensation I’m enamored by. This kind of modality is the best way of thinking for me, and I use thinking in a broad term of something that happens not just in the brain but also in the body.

FC: What did you think would work and it didn’t, and what is the stuff that would surprise you?

MS: In 2015, I was a “food justice” artist-in-residence at the Santa Fe Art Institute. I was interested in the question, What about justice for those we eat? It was my first time living in the Southwest. In New Mexico, it’s legal to carry concealed weapons. So the SFAI, like places that invited audiences inside—the space where I was going to be living and working for the next two months—had a “no guns” sign on the door. Coming from New York, and raised on the East Coast, I had such a strong negative reaction; just fear and revulsion. But I was here, in this place where this was the culture. I had to get my head around this reality that was unfamiliar to me in order to understand what it really was. So, I decided to learn to shoot guns and try to kill something to eat, in order to understand how I felt about both these contentious issues: taking lives for nourishment, and gun culture in the U.S.

I thought I would become a vegetarian, but I didn’t, not at all. It was through the process of attentively skinning the animal that I came to terms with the fact—and really came to terms, also in my body—that some beings give up their lives to nourish others. For many years though, I wouldn’t eat meat if I didn’t know the person who killed the animal. I made a film about this process. It’s called Imagined Lines and Alibis. And this film is my least popular work. Perhaps it’s difficult to witness the process of a wild animal becoming food. It was strange to me. A few years earlier, I made a short film, Making Human Cheese, where I turn a human’s milk into food, and people really loved this film. But the process of animals turning into meat (an everyday process that is much more prevalent in our society), this film didn’t really work, it seems.

On the other hand, GHOSTFOOD, is a work that was very successful. GHOSTFOOD is a food truck that serves flavor simulations of foods that might soon be unavailable due to climate change. There’s this Direct Olfactory Stimulation Device (DOSD) that I designed, that you wear on your face in order to hold the scent of a soon-to-be-extinct flavor to your nose. That’s paired with an edible textural substitute—something you eat that has a similar texture to the climate-change-threatened food, but with a rather neutral flavor—and it’s made from climate-change-resilient foods.

So for example, you smell cod, but you eat a chewy substitute made of vegetable protein and soy. It mimics the texture rather than the flavor of the food we’re trying to simulate, while the scent provides the flavor experience. GHOSTFOOD was made in collaboration with Miriam Songster, and originally commissioned by Marfa Ballroom and a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation grant for Marfa Dialogues/NY.

The project works well for a couple of different reasons. First, it’s a novel and sensory experience that’s both attractive and enticing. Conceptually, it locates this big abstract idea of “climate change,” that’s on a scale that’s difficult for us to process, into something that is in your body. And, as people are pretty familiar with eating and how that’s a part of your everyday life—it makes the impact of climate change real and felt and personal in this way. And just to say: This was 2013, when the reality of climate change was still being debated in the U.S. public discourse, when the level of fires and floods were not as intense and felt as they are now.

The performers working the GHOSTFOOD truck were trained using a method I devised by adapting the Open Dialog approach. Open Dialog is a Scandinavian psychiatry methodology for dealing with psychiatric breaks. You bring in everybody, all stakeholders around this person suffering a crisis, and you put everybody on an even field—no hierarchy of one person’s reality being more ‘real’ than another’s. And then, you talk. There are three primary principles in Open Dialog: “tolerance of uncertainty,” “dialogism,” and “polyphony.” We adapted this approach, and performers used this method to reflect with the audience on their experience, which, combined with this fun but strange sensory experience, allowed for different ideas and conversations to come up around the intense political fight happening at that moment about the reality of climate change. GHOSTFOOD allowed a unique and sensory way in.

FC: For your Onassis residency as part of its 2022-23 Tailor-made Fellowships program, you’ll be employing a technique called attention-deconcentration as a research methodology. Can you tell us more about that project?

MS: It’s something new and a bit esoteric that I learned through my free-diving practice. The world champion diver Natalia Molchanova taught her students this method, attention-deconcentration, and I started looking into it. It’s a technique for managing your perception. When the inventor of the method, Oleg Bakhtiyarov, talks about it, he likens it to the state of being that happens when you’re in mortal danger, or on the hunt.

We usually pay attention by concentrating on one specific thing, and we put all our energies into that. Using this method, if we want to understand what’s happening in an entire field, we must move our attention from one thing to another. If you need to react quickly in a situation; you don’t have time to scan; you need to be aware of the total picture. The other element is about sustained attention—it’s hard for our brains to remain concentrated on a specific point for a long time. Attention-deconcentration enables you to remain aware of the entire field, while staying relaxed. It’s a kind of diffuse but constant attention.

I’ve started using attention-deconcentration as research methodology. My projects are often bringing many different ideas, modes, histories, and bodies of research together. And I love seeing how things are connected, and facilitating these connections through my work. But it’s always me. I’m the one constructing the narrative, consciously or not.

So, I’m interested in using attention-deconcentration to look at things more, and let the narrative emerge, see what happens.

FC: How do you go about this to make it happen?

MS: Let’s start with the visual field. I look straight ahead, relax my eyes, and I just notice, without moving my eyes, the very right edge of my visual field. Then I do the same thing with the left. So then, I hold both in my attention simultaneously—without moving my eyes back and forth. Then I add the top and bottom, so now I want to hold the top, bottom, left, and right. Then you add the entire perimeter and eventually add the whole field. So, everything you see has an equal amount of attention to it. It seems simple, but it’s quite challenging at first.

FC: What advice do you have for aspiring designers and creatives?

MS: The most important thing I tell students is that you need to get out into the world to understand the context of your work. In reality, things are always so much more complicated and contradictory than we think. And also, of course, to get inspired.