- | 8:00 am

What 11 top designers want to redesign in 2026

From look-alike SUVs to AI interfaces, designers from Figma, Microsoft, Pentagram, and more reveal the objects, places, and experiences they’re working to improve this year.

Yes, there are the New Year’s traditions of setting ambitious goals and ditching bad habits, but one evergreen resolution that ought to top lists is to banish bad design. Why endure something that simply doesn’t work (or is an affront to aesthetics) any longer than we have to?

In the spirit of fresh starts, we polled experts in architecture, tech, industrial design, and urbanism on the everyday annoyances and the big-picture issues that they think are in desperate need of a refresh in 2026. (Top on my personal list? Eye-searing headlights.)

Design is inherently an optimistic act, and by fixing these issues, we’re a step closer to a more beautiful and better world.

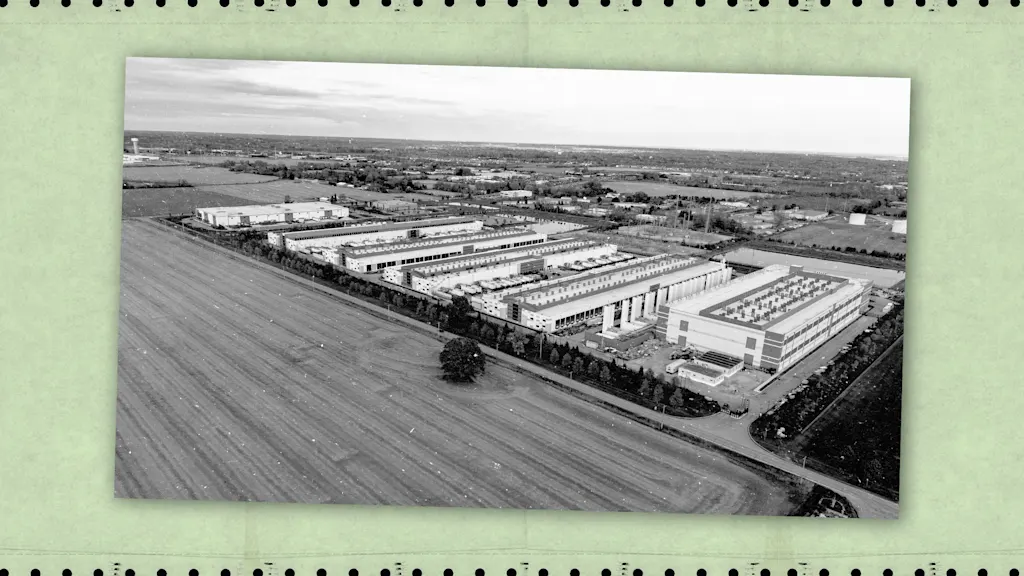

Data Centers

Data centers are the significant buildings of the moment, and we have a responsibility to make them part of our cities as they’re really powering the future. The buildings have to perform at the highest technical level, but they also need to connect and respond to a sense of place and to the community around it. For example, we designed a data center with a facade that has an intricate pattern language that feels more like a theater or civic building and other centers with mass timber, which lends warmth and beauty to the structure while also bringing a sustainability story to the structure.

Every data center project of ours now starts with thinking through resilient strategies, including reducing or eliminating evaporative cooling and integrating next-generation thinking on energy usage. At the same time, there are people still working in these buildings and there needs to be consideration for the workplace as well. It’s about technology plus people, and we can’t ignore the human side of this because recruitment and retention are still key considerations.

It’s also interesting to think about what to do in a really dense urban environment. We’re involved in conversion projects that take aging, underutilized office buildings and explore vertical mixed use. It’s not just about converting office to residential, which we’re doing in many locations. Can you take an aging office building and part of its reuse becomes a data center? In 2026, we’ll see more of a global dialogue from a real estate standpoint on urban opportunities that includes thinking about data centers vertically.

—Jordan Goldstein, Co-CEO of Gensler

Crossover and Compact SUVs

Living in Los Angeles, I’m surrounded by automobiles all day. I’m always disappointed by how homogenous so many archetypes are. Crossover and compact SUVs are all so similar that you could swap the badges on any of them, and no one would know the difference between the brands.

Unfortunately, over the last decade the same can be said of most sports cars. All the major brands have adopted the wide rear body of the [Porsche] 911, and for no reason; their engines are in the front of the car and don’t demand the stability and width to balance the weight that sits on the rear wheels of the 911.

Every brand has an origin story, and many of their older iconic cars were based on original ideas. As recently as the ‘90s, car brands held a unique design language. In the past, the only market that had homogeneous design was the Soviet Union. Our culture is based on differentiation in the market, where customers have choices. Today we lack real choice.

This all points to a lack of vision and conservative leadership at the major automakers. There is no risk-taking, and the customer is given a design that’s the result of market research rather than innovation and design. This should be a priority because it instills poor values—lack of originality, fear-driven business strategy, zero risk-taking—on the built environment and our culture.

—Jonathan Olivares, Creative Director of Knoll

Data Ownership

Every time we swipe our MetroCard, visit a doctor, buy groceries, or scroll through our phones, we are creating data. But we almost never get to see it to understand ourselves better. The data flows in one direction only, from us into systems that are used to optimize operations and algorithms and train models. What if instead our data could come back to us in a form that can help us see the patterns in our lives and understand our own stories? I want to redesign this fundamental relationship.

The issue is that data has become the language that we need to navigate life but we haven’t been taught to speak it; and the interfaces that could help us learn are designed for administrators and quarterly reports only, rarely for actual people trying to understand their own lives. Imagine getting home from a doctor’s appointment and receiving a beautiful understandable visualization of your health over time, where you can see patterns you didn’t know existed. This is the type of context that can help us ask better questions about our health.

Or imagine your transit system revealing the mundane rhythms of your own life back to you (the coffee shop you always stop at on Tuesdays, the routes you take when you’re stressed versus calm). This would close the literacy gap by making data comprehensible in the moments when it matters most without dumbing down complexity and nuances. I’ve spent my career proving we can do this. Better design here means more agency. It means people who can advocate for themselves. It means closing the gap between those who can speak data and those who can’t.

—Giorgia Lupi, Partner at Pentagram

AI Interfaces

I’m excited to see how teams rethink and redesign user interfaces for an AI-native world. Today, we’re still in the MS-DOS era of AI where every prompt, every agent, and every emerging modality is, for the most part, a long text response in a conversational interface. My prediction is that in 2026, we’ll see a shift toward richer, more dynamic interfaces where both inputs and outputs evolve far beyond text.

It’s not surprising that AI user interfaces began as chatbots. Large language models operate on tokens, and text is the fastest, cheapest medium to build, debug, and evaluate. But decades of software and interface design have made something clear: humans don’t think in language alone. We think spatially. We understand through motion, contrast, hierarchy, and causality, and our instinct is to act through direct manipulation, not just typed commands.

As AI capabilities evolve, design is more important than ever. Visual interfaces aren’t going away, and neither is the need to see, shape, and refine ideas as we work. Designers have a rare chance to define the rules and patterns of this new interface era, shaping what work, play, and productivity will look like for decades to come.

—Loredana Crisan, Chief Design Officer of Figma

Material Labeling

When anyone (architects, clients, contractors) walks into a big-box store, it would be transformative to see a Nutri-score or Local Law 33 energy grade for materials, but for wood in particular since it’s so widely used. A better system would treat wood like food, with clear, standardized material labeling. You should be able to see where the wood comes from, almost like buying eggs when you’re faced with this wall of different levels of chicken torture.

Material supply chains struggle with standardization and transparency for many reasons, but in my opinion, it is because consumers didn’t know they should be demanding it. For example, once it became clear that Quartz countertops were causing silicosis by those cutting the material, consumers were horrified. So much so that the Australian government made the material illegal. The problem is big-box retailers, where most wood is purchased, rarely surface this information, despite occasionally stocking high-quality or responsibly sourced material hidden in plain sight.

Greater transparency at the point of purchase would empower people to make more precise decisions about a whole host of values that are important to them. When I walk into a box retailer, I want to know which 2xs are Code A (regeneratively cultivated through methods of land conservation and repair by a local within 100 miles who has been historically disenfranchised) or Code B (selectively harvested and replanted by a fifth generation land and sawmill owner using Indigenous cool burning to prevent forest fires) or Code C (small batch monocultures grown at high efficiency to prevent the replacement of biodiverse unproductive forests), etc.

—Lindsey Wickstrom, Architect and Founding Principal of Mattaforma

Outdoor Lighting

How about we all start taking a neighborly approach to outdoor lighting?

When colleagues and friends talk to me about lighting, they used to mention wonderful festival lights they had just seen or lamps they appreciated or hated. But these days they mostly complain about light streaming into their windows from someone else’s outdoor lighting.

In the city, a new commercial tower in midtown streams constantly changing light into bedroom windows literally miles away. Entertaining for some, apparently, and intensely disruptive for others. Not to mention the damage to fish and bird habitat.

In a suburban neighborhood, unshielded lights placed over garbage cans to scare off raccoons are more than an eyesore. On a motion sensor, they can wake sleepers in nearby homes every time a critter or a pedestrian passes by. Motion sensors have their applications, but unshielded lights attached to building exteriors flashing on and off are frankly anti-social.

For those who live by a body of water or out deep in the countryside, it is often the lone ill-considered, unshielded building/garage light pointing straight out that disrupts the view, the sleep of those in its path, and the wildlife.

What to do? I would ask architects to think outside their interesting boxes. Take a nighttime tour of the surrounding neighborhoods and look back at their building. Then try to visualize the impact their planned exterior lighting and integrated lighting displays might have at a distance.

It’s hard for me to imagine a missing piece of lighting equipment from our well-supplied lighting design world. What’s missing is a change in attitude. A thought for others and some consideration for how our choices impact other people and the species that surround us. It’s not that complicated.

—Linnaea Tillett, Founder of Tillett Lighting Design Associates

Sports Districts

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, large-scale entertainment and sports districts were built in cities across America. These areas were designed with one very lucrative function in mind: to cater to massive crowds of sparsely scheduled mega events. But the other hundreds of days a year, these spaces sit largely empty with limited activity or use.

Today we have an opportunity to redesign these districts so that they not only accommodate dynamic, memorable, and safe experiences around game days, concerts, and conferences, but also support people who want to sit with a coffee in the middle of a Tuesday or meet friends for a live performance, art class, or outdoor movie screening on the weekend.

To do this, we need to introduce flexibility and comfort. Multipurpose plazas can cater to large events but also provide comfort day-to-day with furniture and features that serve many purposes. Imagine a large plaza designed for a tailgating crowd but also designed to transform with lots of moveable furniture under a shaded tree canopy for gathering on a non-event day. Stepped wooden platforms can be used as a stage or also for seating or play. Wide sidewalks with large trees for shade and street furniture (e.g. benches, planters, bike racks, lighting) create great urban streets while also being designed for crowd security and protection.

As we head into a multiyear period of American cities preparing for mega events like the World Cup, the Olympics, and the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, designers working on event spaces should remember that the motivation to rehabilitate these places shouldn’t be either function for large events or daily life. It’s both. Enduring urban spaces should be able to do it all.

—Chris Merritt and Nina Chase, Founding Principals of Merritt Chase

MRIs

Today, getting an MRI—which is essential for diagnosing life-threatening conditions—can mean long wait times, discomfort during lengthy scans, and limited availability in low‑resource settings. Globally, about 70% of people have no access to MRI at all, creating massive delays in diagnosis and care.

For patients, this can translate into anxiety and late detection. For radiologists, rising volumes add to burnout. And for developers, innovation is slowed because new algorithms can take weeks to deploy on scanners. A redesign of MRIs could make them faster, more comfortable, and dramatically more accessible.

Historically, MRI systems have been hardware‑centric and siloed, with reconstruction tied tightly to the scanner. Lower‑cost hardware options exist, but their images are often noisy or distorted. All of this creates bottlenecks: developers can’t easily test new algorithms, patients endure long scans, and radiologists face mounting workloads. The result is inefficiency and inequity. Advanced imaging remains concentrated in well‑funded hospitals, while less‑resourced regions often lag decades behind.

Software-driven approaches—like Microsoft Research’s Tyger framework, which is an open-source project effort that I lead—show how MRI can evolve into an intelligent imaging system, where cloud‑based reconstruction and AI‑driven denoising make scans faster, more scalable, and ultimately more equitable.

—Michael Hansen, Director and Principal Researcher, Microsoft Research, Health Futures

Accessibility that ‘Others’

I’m expecting 2026 to be the year where truly accessible design becomes mainstream in mass-market products. Not as a checkbox idea, not as a product for others, but as a cost of entry baseline strategy. All products should be designed through the filter of accessibility so they appeal to the largest possible market segment and work for longer periods of time.

The problem is there is so much stigma associated with aging and disability and so much of it is because the objects have always looked medical and they’ve made people feel othered and they remind us of what we can’t do. And we think the power of design is to break down those stigmas and allow people to make positive emotional connections to these objects.

As we think about it, everybody is disabled. There is permanent disability: you get a diagnosis, you get into an accident, you get older. There is temporary disability: you get a sports injury, you become pregnant, you’re recovering from surgery. And there is this notion of situational disability that almost nobody thinks about: You’re outside on a sunny day and there’s a glare so you can’t see your phone. Or you’re walking through a grocery store holding a baby and you’re one-handed all of a sudden.

We all strive for universal design, but the reality is there’s never going to be one version or a product that is perfect for everybody. However, if everybody who makes those objects is thinking about addressing the largest group of people possible, then everybody will be able to find the one that is right for them.

—Ben Wintner, CEO of Michael Graves Design

Small-Scale Parks

For decades, landscape architecture has emphasized large-scale and highly designed and programmed projects that take many years and multimillion-dollar price tags to develop. No shade to these projects—we will never say no to a beautifully designed park—but there is a very real need for different kinds of publicly accessible green and garden spaces in our cities, especially considering how public funding to create and maintain them is becoming increasingly constricted.

When it comes to green space, maybe the solution is to make many small plans instead of one big one. Instead of spending millions on one park site, what if we designed a network of smaller and neighborhood-scale green spaces where communities can be directly involved in building and gardening, maintaining, and caring for them?

Rather than going through months of rendered and CAD-ified design concepts, we could take a scrappy and interactive approach, getting our hands in dirt and designing by doing. Use locally appropriate and sourced plantings and materials, repurpose what’s near or on site, grow from seed, and find creative ways to turn reclaimed materials into seating, furnishings and platforms. This will reduce resources and build in a way that is less carbon-intensive and more ecologically regenerative.

—Kasey Toomey and David Godshall, Landscape Architects and Partners at Terremoto

Intelligent Experiences

What most needs redesign isn’t something physical; it’s the software that shapes our homes, workplaces, and communities long before anything is designed or built.

Over time, our tools have become incredibly powerful, but they often demand more attention than they should. As the pressures on how we live and build grow more urgent—around improving sustainability, affordability, and resiliency to the impacts of climate change—we need software that does more than help people work faster. It needs to help them make better decisions, to adapt in real time and learn from behavior in order to anticipate needs and personalize experiences.

As we move into the agentic era, the playing field is changing fast. I’ve seen how easily attention gets pulled toward managing tools instead of weighing the choices that truly matter: carbon impact, cost, livability, and long-term performance. When that happens, good intentions get buried under process.

The real promise of AI isn’t automation for its own sake; it’s building with intention. Imagine a world where a user can simply talk, describe what they want to build, then be presented with solutions, and rapidly ideate on their ideas without ever having to use their keyboard or mouse. Those capabilities are here.

Used responsibly, AI can reduce friction, surface the right considerations at the right moment, and let designers and planners focus on outcomes rather than mechanics. A better-designed future is one where technology steps out of the spotlight and helps better choices become the default, not the exception.

—Heather McIntosh Cassano, Vice President, User Experience, AEC Solutions at Autodesk