- | 8:00 am

Why we built cities for cars, not people, and how we can fix that

A five-point plan for reimagining urban environments.

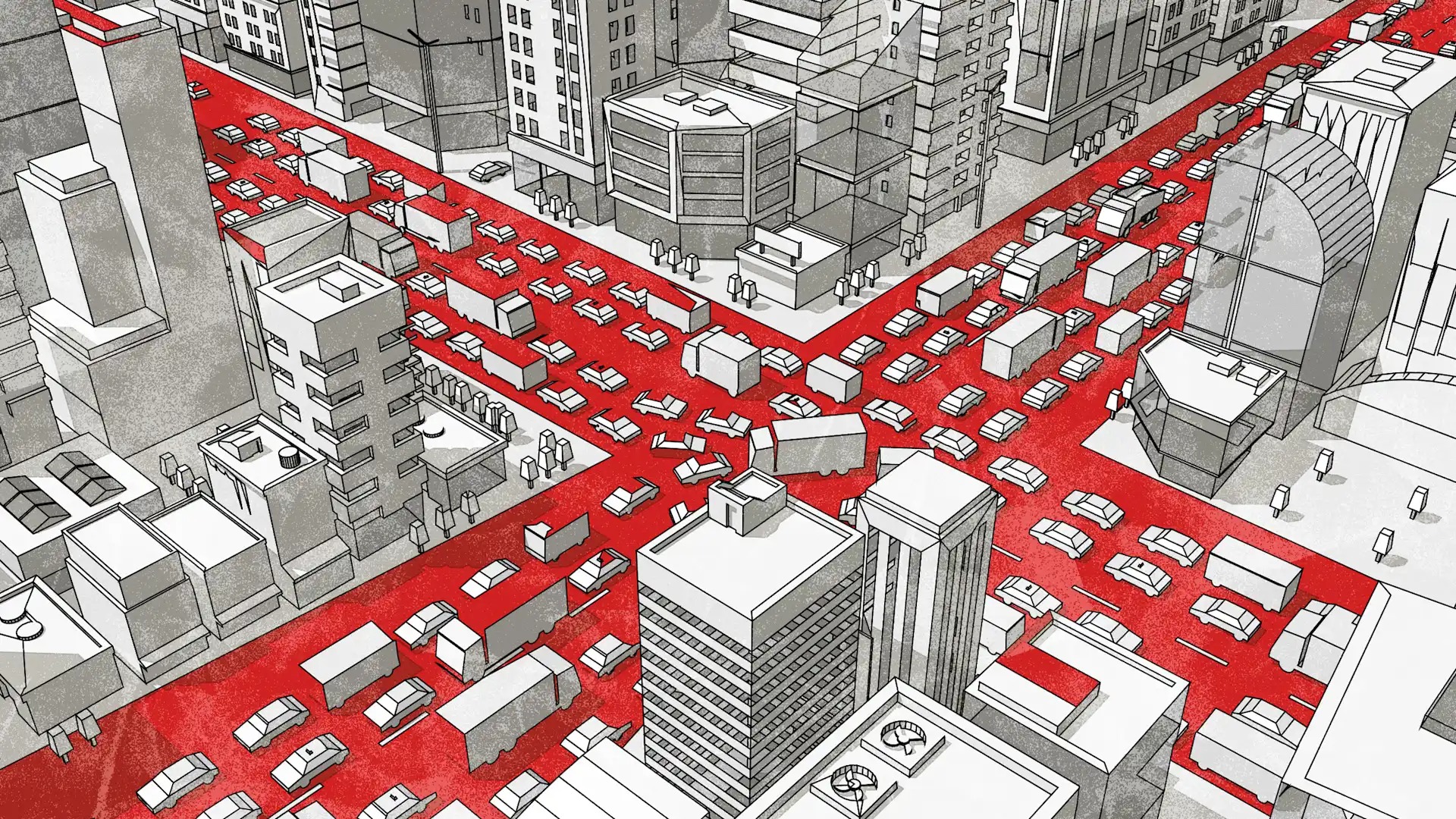

The modern city is a paradox. Designed to bring people together, it increasingly keeps us apart, stranded in traffic, saddled with debt, and choked by air pollution. The root cause isn’t a mystery. We built our cities around cars, not people.

This design wasn’t accidental. It was the result of a century-long entanglement between public infrastructure and private interests, what we call the car-industrial complex. Cars were sold to Americans as symbols of freedom and progress. In reality, they’ve become financial traps, consuming vast portions of household budgets while gutting public space and mobility options for everyone.

Car-centric planning has hollowed out our cities. Zoning regulations, freeways, and cheap fuel gave rise to sprawling suburbs and isolated communities, dependent on personal vehicles for even the most basic tasks. It’s a system that punishes the poor, marginalizes the elderly and disabled, and makes public life thinner and more precarious. The car promised freedom, and delivered debt, pollution, and dependence.

Meanwhile, local governments, seduced by auto industry lobbying and federal subsidies, doubled down on road-building and car-friendly development. The result is a vicious cycle: more cars mean more roads; more roads mean more sprawl; more sprawl means more cars. And all of it costs taxpayers dearly. Cities are now stuck maintaining bloated road networks while struggling to fund basic services like public transit, schools, and housing.

Reallocating space

So how do we begin to reverse this?

First, we must redesign our cities around people, not cars. This begins with reallocating space. Cars are the most spatially inefficient form of transport ever invented. They sit idle 95% of the time, yet take up 50% or more of urban space in some cities. The solution? Reduce car lanes. Convert parking lots into housing, green space, or local commerce. Make streets walkable and bikeable by default, not as an afterthought. This can be done and is already being done in cities from Barcelona to Bogota.

Second, we need to invest in public transit, not just as a social good, but as core infrastructure for economic resilience. This means buses, trains, but also microtransit, demand-responsive services, and protected cycling infrastructure. Public mobility must be convenient, affordable, and desirable. A truly resilient city isn’t one where everyone can afford a car, it’s one where nobody has to have one one to thrive.

Third, housing and mobility must be planned together. For decades, we built homes far from jobs, schools, and groceries, and then told people to drive. Inverting that logic is essential. Cities should incentivize mixed-use, infill development and eliminate minimum parking requirements that bake car dependency into every building project.

Fourth, we must confront the car-industrial complex at its core: finance. Car debt in the U.S. now totals more than $1.6 trillion. That’s more than all outstanding student loan debt. Eighty percent of new cars and 35% of used cars are purchased with loans, many predatory, high-interest, and longer than the expected life of the vehicle. This isn’t mobility, it’s a form of economic capture.

Governments can’t fix this by tinkering at the edges. Subsidizing electric cars or building a few charging stations won’t solve the deeper problem: the financial architecture of car dependency. We need policies that actively disincentivize car ownership and use, congestion pricing, car-free zones, and removing subsidies that make driving artificially cheap. At the same time, we must support families through affordable alternatives, dense, walkable neighborhoods, better public schools, and reliable transit.

Fifth, we must reimagine how we measure success. For decades, traffic engineers and city planners envisaged good planning in terms of how fast and efficiently traffic could flow. We need to shift that metric toward human flourishing and what makes a city liveable in the 21st century. Is it safe to walk your child to school? Can a teenager get to a job without a car? Are parks and clinics accessible without driving? If not, the system is failing.

Not a dream

Reversing car-centric design is not a utopian dream. Cities around the world are already doing it. Paris is removing 70,000 parking spaces to make room for bikes and trees. Barcelona is expanding its network of “superblocks” that prioritize pedestrians and eliminate through-traffic. Oslo removed cars entirely from its city center and saw foot traffic, and local business, surge. Cities in the Global South are pioneering new forms of green micormobility, such as Jakarta where the government has set a target of electrifying 2.1 million motor cyles by the end of 2025

These changes we need in cities aren’t just about mobility. They’re about public health, economic equity, and climate resilience. They’re about repairing the social fabric that cars have slowly unraveled. And most importantly, they’re about freedom, not the isolated, debt-ridden version sold by car commercials, but the real kind: the freedom to move, to breathe clean air, to live in a thriving community.

Adapted from Roadkill: Unveiling the True Cost of Our Relationship with Cars, by Henrietta Moore and Arthur Kay. Copyright © 2025 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.