- | 3:00 pm

What is ghost gear? The most deadly form of ocean plastic pollution, explained

It could be responsible for up to 30% of the decline in marine species, including dolphins, sharks, and turtles—and the critically endangered porpoise.

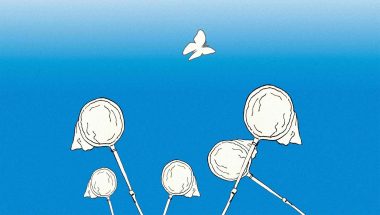

Most of us are aware of the manmade plastic pollution that ends up in the world’s oceans and washes up on its shores: the straws, bags, and balloons that regularly harm marine life.

But there’s a greater pollution threat lurking deep underwater, and it’s likely far deadlier to sea life. It’s the lost and abandoned fishing equipment known as ghost gear, which continues to trap creatures long after being discarded. “This is something you cannot see from the surface, [so you can] be blissfully unaware of,” says Joel Baziuk, associate director of the Global Ghost Gear Initiative (GGGI), an international coalition of public, private, and nonprofit entities to reduce the threat of ghost gear, led by the Ocean Conservancy.

Ghost gear has a considerable environmental and economic impact, and it’s in everyone’s interests, from environmentalists to fishers to seafood companies themselves, to find solutions to remove the equipment and prevent more from settling in the oceans.

WHAT KIND OF GEAR IS MOST COMMON?

Ghost gear refers to industrial fishing equipment that has been left behind in oceans, whether accidentally or deliberately. That includes fish traps and crab pots, hooks and lines, and trawls. The worst offenders are gillnets: a type of “passive” fishing gear that hangs vertically and waits to ensnare fish passing by; their heads will fit through the mesh, but their bodies won’t. Some nets can stretch 10 to 50 feet deep, and up to 2 miles long.

Ghost gear has more detrimental effects than other plastic debris because it continues to catch fish, even when lying dormant deep under water. “[It’s] the most harmful form of marine debris, pound for pound,” Baziuk says, “because it’s designed to capture aquatic life.”

HOW MUCH IS THERE?

Estimates suggest ghost gear is about 10% of global marine litter, which could be between half a million and a million pieces annually—though Baziuk says the global figure is tough to accurately predict.

He says there’s more value in looking at local hotspots. Between California and Hawaii is an area of the ocean nicknamed the Great Pacific Garbage Patch because the strong currents of the North Pacific Gyre pull in massive quantities of debris. The ghost gear there is estimated to be 46% of the 45,000 to 129,000 metric tons of total floating plastics.

In South Korean waters, 39,000 metric tons of nets are abandoned every year; and in Canada’s Greenland Halibut fishery, 70 kilometers (about 43 miles) worth of gillnets were found in just five years.

WHAT CAUSES THE BUILDUP OF GHOST GEAR?

The great majority is lost by accident, says Baziuk, who previously spent 20 years working in the fishing industry with the largest commercial fishing harbor in Canada. “No fisher ever wants to lose their gear,” he says, including illegal fishers, because it’s costly to replace.

A huge cause is extreme weather. Climate change is contributing to more intense storms, during which fishers may have to leave gear behind out of safety. Equipment may also get snagged on reefs, rocks, or wrecks—or on other ghost gear below. Baziuk says most fishers will try to go back and recover lost gear, but it’s not always possible.

There are times when fishers do discard gear on purpose. Often, that’s in developing nations where there’s a lack of waste-collection infrastructure. “It’s not out of [malice]—it’s due to a lack of alternatives,” Baziuk says. “What are you going to do with a net that weighs 1,000 pounds or 20,000 pounds at the end of its life?”

WHAT’S THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT?

Effects on sea life have been disastrous. Creatures including whales, dolphins, sharks, rays, turtles, and sea birds become entangled in the gear, then die often slow deaths from suffocation, infection, or injuries resulting from trapped limbs being pulled from their body.

For example, an estimated 1,500 sea lions in Australia die each year from entanglement, including on plastic twine, ropes, and nets. Most of those were pups and juveniles, perhaps getting stuck while playing.

The vaquita, a porpoise in the Gulf of California, is critically endangered chiefly due to dumped gillnets from illegal fishing. In 2021, the Mexican government ended a “no tolerance” zone in the Upper Gulf, reopening it to fishing. But if irresponsible fishing doesn’t stop, the vaquita could become extinct in the next few years.

WHAT’S THE ECONOMIC IMPACT?

Ghost gear unintentionally catches harvestable seafood; Ocean Conservancy estimates that 90% of trapped marine life is of commercial value and that some fish stocks have experienced a 30% decline in numbers.

That’s a threat to the livelihoods of fishers, many in developing nations—as well as to global food security. “That’s the means by which they harvest aquatic species in order to feed their own families, as well as the rest of the world,” Baziuk says.

CAN THE GEAR BE REMOVED?

It can be, and there are many efforts underway. The Gulf of Maine Lobster Foundation, which has been organizing “removal trips” for 15 years, has found thousands of tons of apparatus—including, on one occasion, a single 20,000-pound “gear ball,” a mass of different gear jumbled together. They tow them back to shore (they’re sometimes too heavy to place on the boats), and recycle them at a facility in Maine.

But removal is expensive, and it’s hard to locate gear in vast expanses of the ocean that’s hundreds of meters deep. Baziuk suggests that it’s best to focus on critically endangered habitats, like coral reefs and mangroves and places like the Gulf of California, where the vaquita is in critical condition.

But the best method is prevention, ensuring the plastic doesn’t end up in the ocean in the first place.

HOW CAN IT BE PREVENTED?

Education is key. Fishers know it’s happening, but many don’t know the extent of the problem; and once made aware, may choose to improve methods. And the more the public knows, the more it can try and advocate for change with government representatives. So, much of the GGGI’s outreach is educational in nature, Baziuk says.

The GGGI has best-practice frameworks for different entities, including governments, fishers, and manufacturers. For example, fishers can try to fish in less extreme weather when possible or away from where other fishing occurs, so gear doesn’t get tangled in existing equipment. They can also disclose their losses to GGGI’s reporting app.

Manufacturers of fishing gear, meanwhile, can find new ways to produce biodegradable equipment, as well as more easily traceable gear.

WHAT ABOUT AT THE INTERNATIONAL LEVEL?

The GGGI is fighting to ensure that ghost gear is a key part of the UN’s upcoming global plastics treaty, which is currently under negotiations. In the last resolution in 2022, ghost gear wasn’t mentioned at all. Baziuk argues that the treaty needs it in a special category because it requires different solutions from other pollution problems.

The second round of negotiations is taking place this summer in Paris, and the GGGI will be advocating for ghost gear provisions.