- | 9:00 am

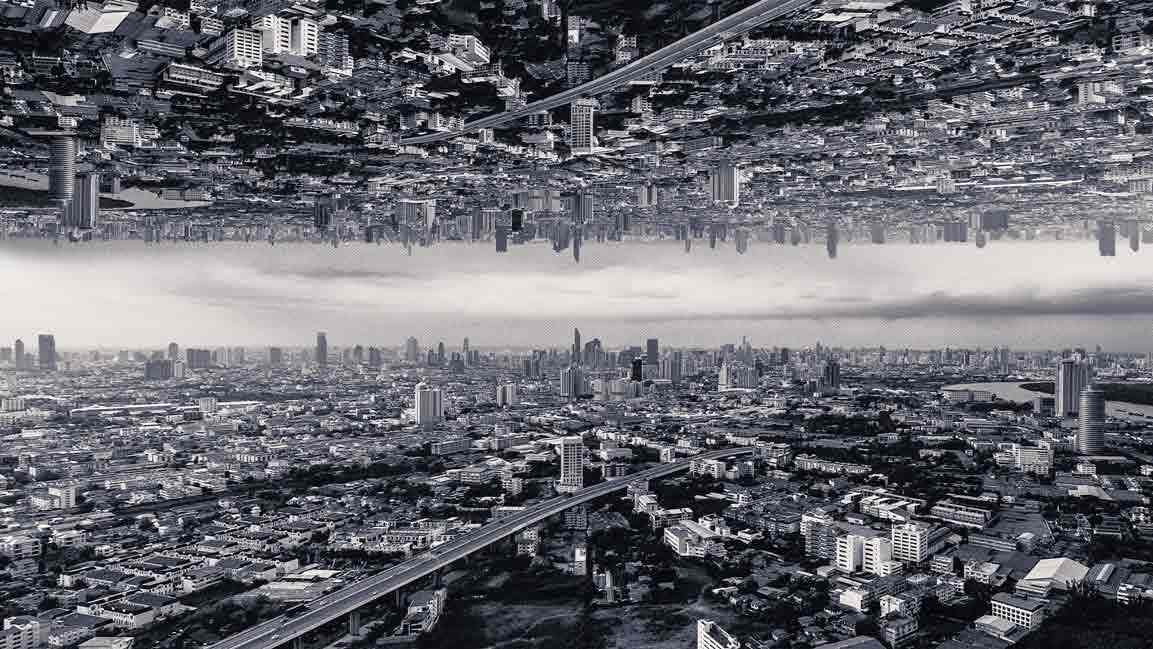

Do all cities in the Middle East look the same? It is time to rethink how we build cities

Given the precedents for inspiration within the region, experts say cities need heterogenous design solutions that are unique

The Middle East is home to an incredible diversity of regional architectural and planning styles. But somewhere along the way, we lost the plot.

One can’t stop noticing. Glass-and-steel skyscrapers have appeared all over Dubai, Doha, and Riyadh, indifferent to their surroundings. The developers take great pains to describe their sensitivity to local traditions, both social and architectural. But sadly, the developments have a numbing similarity right down to the central business districts.

Even the luxury condos, malls, marinas, coffee shops, bars, and restaurants look and feel familiar.

And each is more placeless than the last.

Why does it feel like cities are copied and pasted? This strikingly sameness among the new cities can be traced to a few factors.

On the one hand, the glossy look is perceived by many as a sign of successful modernity. But it is also true that much of it is a practice of urbanism; it’s a reflection of economic prowess driven by oil reserves.

“The similarity in GCC skylines, characterized by tall glass buildings, is reflected globally,” says David Lessard, Design Director, H+A. “Cities use these structures to project modernity and status, bringing new cities like Dubai on par with established financial centers like New York.”

“To step away from this architectural model risks the perception that the city in question is not on par with the world’s best,” adds Lessard.

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND GLOBALIZATION

The similarity between Dubai, Riyadh, and Doha also stems from their proximity, rapid economic growth, and increased globalization.

“Generally, cities attempt to showcase the modernity achieved by society thus far through their architecture and infrastructure. Making them competitive regionally and globally in attracting business, trade, and further development,” says Nasser Abulhasan, Principal and Founding Partner at AGi Architects.

The similarity of cityscapes across the region goes back to the design mindset from the 80s through the early 2000s, says Sebastien Turbot, a sustainability, cities, and social impact expert at Earthna, when urban planning focused on zoning developments based on their use. “This is why we have industrial areas, residential suburbs, and, of course, visually impressive business districts.”

Pushing the boundaries of technology, focusing on innovation and challenging past norms, have led to taller buildings, more glass, and complex engineering systems, however, Lessard says, this relentless pursuit of modernity is leading to“visually generic, unsustainable, and pedestrian-unfriendly cities.”

From a sustainability viewpoint, Turbot says this approach presents challenges. “By separating areas, cities sprawl, which means people need to travel further to work or access services – often by car rather than public transport, and energy and resource efficiency is not optimized.”

Perhaps this sameness is inevitable when you’re taking a broad view of a region in which over 380 million people are strewn across over 5 million square miles. The globalized population has the same aspirations to live in expensive renderings, in successful modernity, and in the gloss of technological contemporaneity.

BETTER DESIGN IS POSSIBLE

There’s an underlying worry that if this sameness continues, cities could lose the very essence that makes them unique, and people may not feel the difference they offer.

However, understanding deeply can help us broaden our conception of what a city is and can be and what forms urban habitation can take.

Given the precedents for inspiration within the region, some of the world’s oldest cities originated in the region, there’s a sense of depriving ourselves of living in interesting, meaningful, and wonderful cities.

“Better design is always possible,” says Abulhasan, “when architects embrace the space they are designing for.”

When designing, a multitude of aspects must be considered and connected. When local culture, region-specific materials, and climatic considerations are taken into account, architects can create innovative, impressive structures that are also cost-effective.

Learning from and utilizing traditional architectural elements and sustainable local practices will lead to an architecture that is better suited to its environment and has a sense of belonging to a place, says Abulhasan. “This flexibility of fusion between the old and the new adheres to the local customs and reflects a metropolis’ unique identity, creativity, and cultural relevance.”

To come out of this rut, there’s a growing movement for a more human-centric design approach that celebrates heritage, vernacular elements, and the principle of well-being to drive the aesthetic response.

“This shift aims to create more diverse, climate-responsive cities that prioritize residents’ needs over the developer’s agenda – resulting in a heterogenous design solution that is unique to its place,” says Lessard.

THERE ARE EXCEPTIONS

According to Turbot, as we understand more about the value of urban density and walkability and the impact of climate change, cities in the region are considering this in their approach to developing new and older areas.

“Take Lusail – a relatively new area of Qatar – as an example. It’s been designed so you can live, work, study, and shop within walking distance; there is lots of public space, and the area is serviced by trams and the metro.”

There are more exceptions. A place like Qatar’s Msheireb Downtown will feel like a breath of fresh air after all the sameness. It’s ideal for a place to be conversant with its cultures or respond to local tastes and preferences.

It’s a mixed-use development that combines traditionally influenced design with modern technology, creating a sustainable and socially valuable district.

“Its layout drew inspiration from the past, with buildings positioned to harness shade and breeze. However, these are fitted with cutting-edge heat-insulating glass, which helps keep them cool. This layout also means the area is completely walkable, including homes, shops, restaurants, offices, and museums. The need for cars is reduced, and community connectivity and wellbeing are enhanced,” says Turbot.

Another great example is AGi Architects’ designed Wafra Wind Tower in the Salmiya area of Kuwait City. The architects conceived it as a wind tower featuring a central, vertical courtyard that provides natural ventilation to each apartment unit.

The service core is located on the southern wing to minimize sun exposure and consequently reduce energy consumption—acting as a thermal barrier to the rest of the building. Hence, minimum openings are placed on the façade, while on the other hand, the building opens to the north, facing the sea.

Taking the idea of the traditional Middle Eastern courtyard typology and developing it volumetrically, it borrows light and ventilation from the facade, funnels it through the pool area, and flows through all levels, finding its way out through the opposite façade, cooling the entire structure, and ensuring a pleasant climatic experience in a country that can be uncomfortably warm.

It required the understanding and reinterpretation of local environmental techniques, says Abulhasan.“Optimal opportunities for natural lighting and cross ventilation also become an essential driving force for the design, which gives the tower its character and determines its final orientation.”

Then there are other projects that clearly challenge the question of heritage vs. modernity, such as the Al Shindagha Historic District by X-Architects in Dubai and the Sharjah Art Foundation by Godwin Austen Johnson.

According to Lessard, both are cultural projects that inherently question ideas of the past while embracing modernity in a thoughtful and relevant way, “avoiding cliches and setting an example on how vernacular design can be leveraged towards a unique urban character.”

The time to reassess our built world is now. The future of the region’s cities cannot lie in its urban past.

Experts say the region is abundant with unique materials such as stone and mud bricks. Exploring and blending these traditional elements with modern elements results in a distinctive urban landscape. For this to happen, Abulhasan says education about local design heritage and government policies encouraging traditional elements through incentives or regulations are essential.

“Engaging with the specific communities in the design process also ensures cultural relevance while meeting the users’needs, creating architecture that reflects both tradition and modernity and serves the society.”

Turbot says there’s an increased interest from architects, planners, and developers with similar challenges in sharing best practices, exchanging ideas, and developing solutions. “This has led to forming an arid cities network, tailored conventions, and collective research.”

It’s true. We won’t scrap how we’ve been building architecture and cities. But as our world moves faster and becomes more interconnected, we need to embrace a new toolkit of options that is more holistic and responsive.

The future will not be in spectacular megacities with their soulless glass-and-steel skyscrapers but in cities with visual richness and authenticity.

The open question is how this will play out in the region’s urban realm. Some cities may neglect public space in favor of other priorities. However, more architects and developers will eventually devote more resources to strengthening developments that are particularly conversant with any of its cultures, whether through parks, plazas, promenades, community centers, or streets turned over to pedestrians.

“Limiting design freedom is often seen as a hindrance by developers and residents seeking unique, diverse projects. Allowing architects and designers the opportunity to explore the most creative response to a brief without the strict regulations of cities like New York and London has supercharged fast-emerging cities like Dubai to gain prominence,” says Lessard.

“We advocate a culturally conscious approach to contextual design that naturally integrates better building principles, minimizes unregulated development, and preserves the GCC’s heritage while fostering innovation,” he adds.