- | 8:00 am

How a 100-year-old kidnapping set climate tech back decades

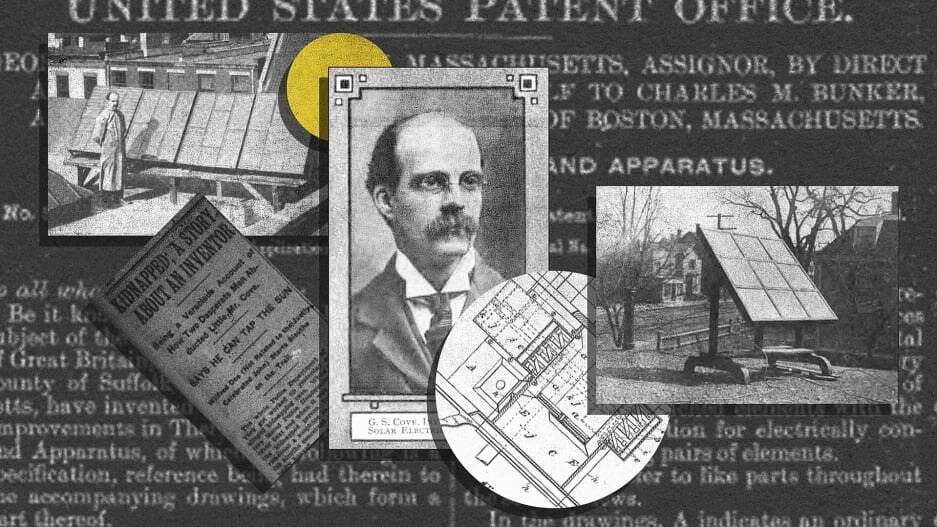

George Cove patented solar energy technology in the early 1900s. Then, after a mysterious kidnapping, his business shut down.

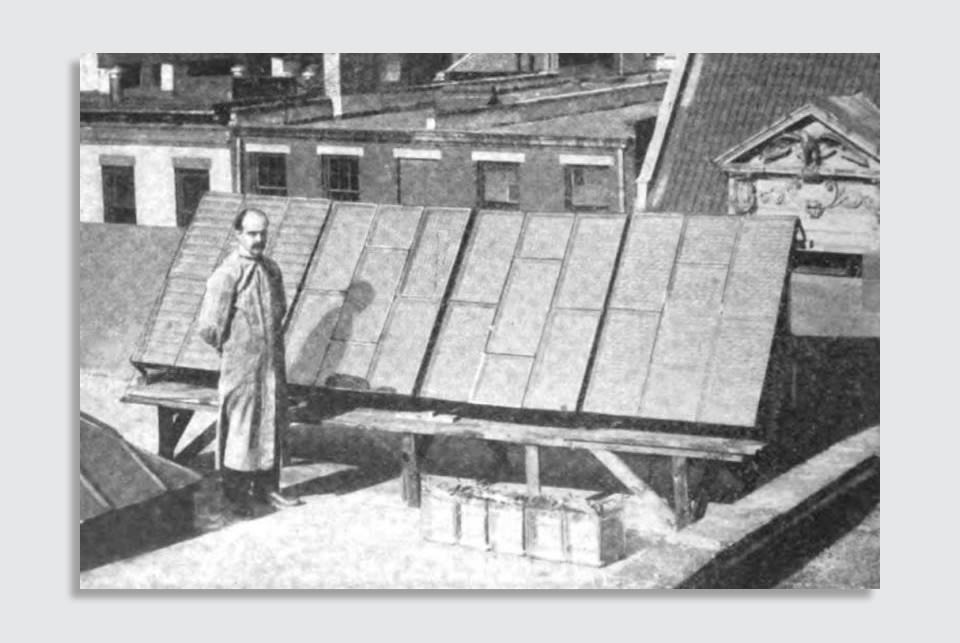

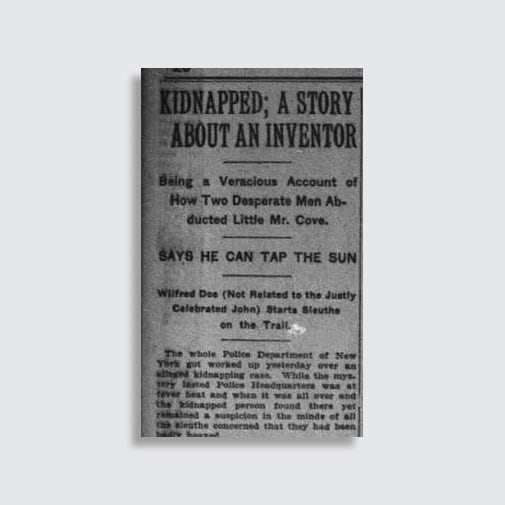

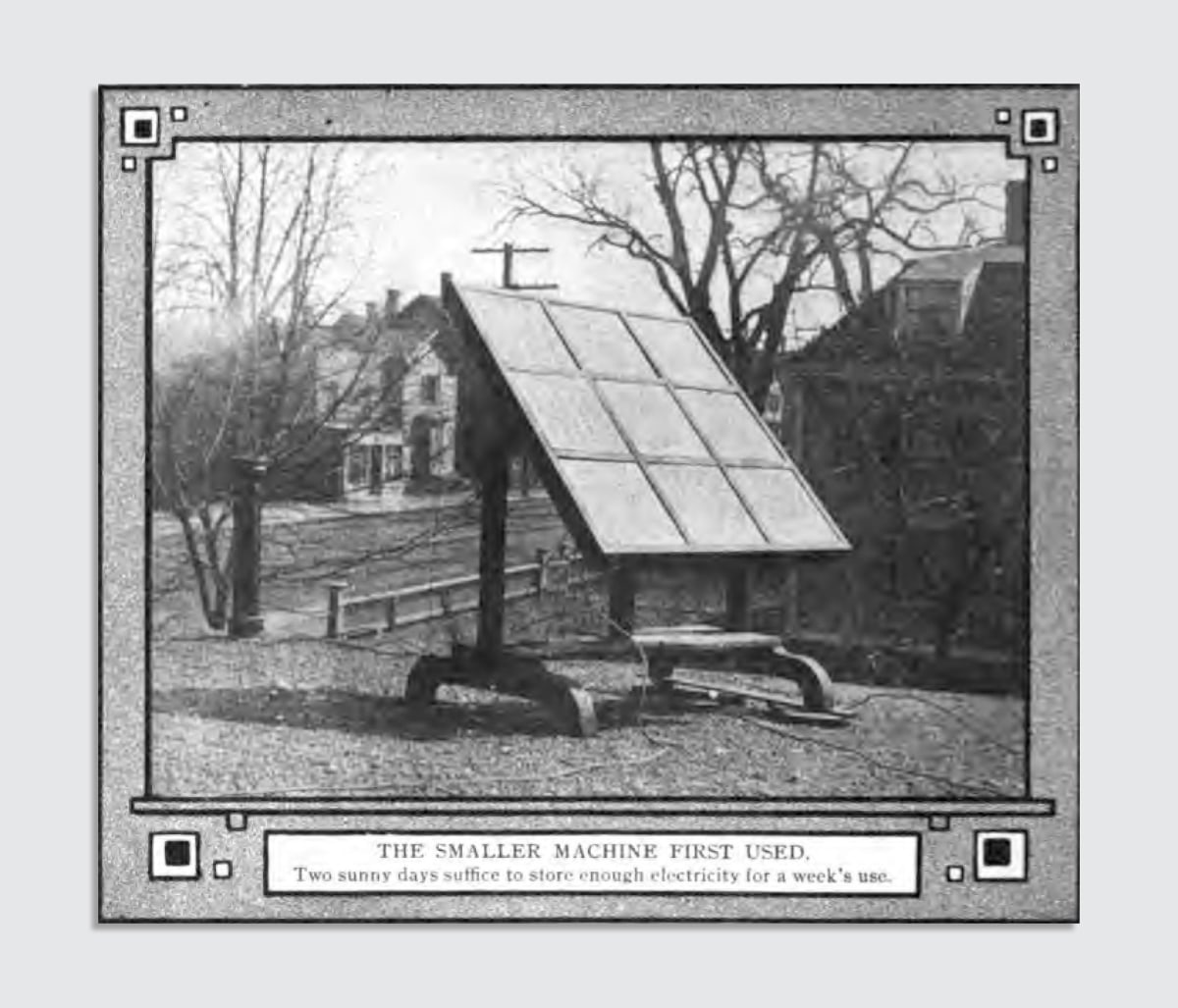

In 1954, Bell Labs created the first commercial silicon solar cell. But more than 40 years earlier, another inventor had launched a business to sell a “sun ray machine” for households. The early solar energy tech—which could power small household devices for a week, and had been demonstrated on rooftops in New York City—was lauded in the press. But then the inventor, George Cove, was kidnapped.

A New York Herald story reported at the time that Cove’s kidnappers demanded that he shut down his business and give up the rights to his solar patents. It isn’t clear what actually happened. (Some speculate that Cove staged the event to generate media coverage, though attention was already surging; others think it’s plausible that another energy company wanted to eliminate the threat of solar, since ruthless business practices were common at the time.) Cove was released and, a year later, the startup, called Sun Electric Generator Corporation, no longer existed. No significant solar R&D happened again for decades.

Oxford University researcher Sugandha Srivastav, who studies innovation in the energy sector, stumbled across Cove’s work when she started searching for the first solar patent. Cove’s patent was granted in 1906, far earlier than she’d expected. It sparked a thought experiment: What might have happened if solar technology had developed without pause since the early 1900s?

“We become better at making solar panels, and their costs go down, the more we make,” Srivastav says. “This is known as Wright’s Law, and it’s observed for renewable energy like solar and wind consistently in the data. So, what if we’d made solar panels from the 1910s continuously up to the present—what if we started four decades sooner than we actually did in real life?”

Even Cove, with a few iterations of his design, saw that it kept becoming more efficient. Of course, it’s impossible to know what might have happened if he kept working—his business might have failed for other reasons. But if he and others had focused on solar tech, and if development followed the expected path, Srivastav calculates that solar power could have become cheaper than coal as early as 1997. In real life, that didn’t happen until 2016 or 2017.

“According to my estimations, it would have happened around the time of the millennium,” she says. “When Al Gore was releasing An Inconvenient Truth. When we were all listening to the Spice Girls. And that would have changed the course of climate action.”

Between the turn of the millennium and 2016, coal power grew by 50%. That might not have happened if solar power had already been cheaper. And earlier solar technology likely would have sparked other changes. “If solar had taken off in 1910, I think we could have even had a very different energy paradigm,” Srivastav says. “If solar was already the dominant technology, I think a lot of people would have invested in batteries far sooner, because it’s the natural and logical next step.”

News stories in the early 1900s also speculated about other potential applications of the technology, including planes running on solar power. “The aeroplane of the future will dart hither and thither, her motors driven by electric energy transmitted by wireless from some far-away Sun Electric power plant,” one journalist wrote.

Instead, fossil fuels became the dominant source of power, and fossil companies fought any alternatives even when they realized, decades ago, what that would mean for the habitability of the planet. “I think the really interesting thing about this whole saga is that we could have had solar competing with fossil fuels from the beginning,” says Srivastav. “But because this initial effort was squashed, we then had incumbent oil and coal industries really just get a huge head start—a 40-year head start. And then to come in at that point and compete is a whole different story, because they’re embedded, they have political connections, and the size is orders of magnitude larger. At that point, it’s a very different competition.”