- | 9:00 am

How fast can a car go from 0 to 60? It really doesn’t matter

The auto industry has pushed this metric for decades. But cars—especially EVs—are so fast that comparing the decimals is pointless and dangerous.

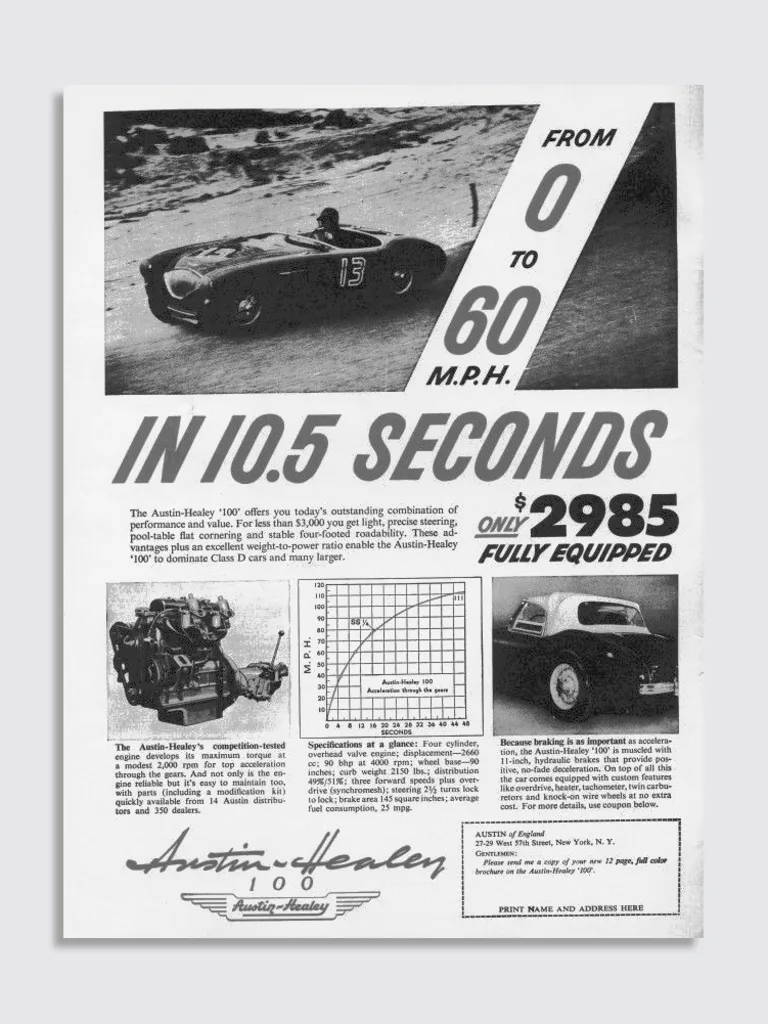

Seventy years ago, British carmaker Austin-Healey sought to wow the public with its “100” sports car model. The company presented its pitch in a 1955 magazine advertisement that promised “light, precise steering, pool-table flat cornering, and stable four-footed roadability.” If that wasn’t enough to impress prospective buyers, Austin-Healey shared a particular performance metric in eye-grabbing red ink: “From 0 to 60 M.P.H. in 10.5 Seconds.”

If you’re not exactly blown away, I don’t blame you. These days, a sports car that needs 10 seconds to hit 60 on the speedometer should be driven to the mechanic. A Ford Mustang, for instance, reaches 60 mph in only 4 seconds, and a Dodge Charger Hellcat takes half a second less. It’s not just sports cars, by the way; even an unflashy 2023 Honda Civic requires only 7.5 seconds, roughly the same as a hefty Chevy Suburban SUV weighing almost 3 tons. When MotorTrend took 220 vehicles out for road tests in 2021, the slowest model was a Nissan Kicks that needed 10.1 seconds to reach 60 mph—still faster than that supposedly speedy 1955 Austin-Healey.

Rapid acceleration has become the rule, not the exception, throughout today’s auto industry. Even the slowest cars rolling out of a factory are quicker than the muscle cars of yore, and they’re more than powerful enough to meet the daily needs of an average driver. But rather than declare victory over sluggishness, carmakers keep harping on their models’ 0-to-60 times, especially for new electric vehicles that are even faster than their gas-powered predecessors. Worse than superfluous, the continued focus on acceleration risks making EVs needlessly inefficient, polluting, and dangerous.

Matt Farah, cohost of The Smoking Tire podcast, noted that the automotive world was a different place two or three generations ago, and 0-to-60 times then provided a useful guide. “Zero-60 is a very ‘Detroit’ metric. The old-school muscle car guys who grew up drag racing really cared,” he wrote in an email.

The first person to popularize 0-to-60 times was Tom McCahill (1907-1975), a car dealer, automotive journalist, and race car driver. According to MotorTrend, in 1946 McCahill began publishing results of his own road tests, including the now-famous 0-to-60 times. McCahill chose his moment well. Although prewar cars were often underpowered (in the late 1930s, more than half of U.S. models couldn’t hit 85 mph on a highway), that changed as the economy moved into high gear after World War II. Along with horsepower, 0-to-60 figures offered prospective buyers a shorthand way to grasp vehicles’ might.

At the time, relatively rapid acceleration could serve a practical purpose, since cars that picked up speed slowly could be stressful to maneuver in situations like merging onto a highway with a short on-ramp. In 1969, advertisements for the economical Toyota Corona prominently featured its then-impressive 16-second 0-to-60 time. (A 1960s Volkswagen Beetle could require almost 30 seconds, according to zeroto60times.com, a website that maintains an exhaustive list of acceleration rates over the years.)

But in recent decades, the utilitarian case for quicker acceleration has grown moot. Steady improvements in automotive design and engine technology have caused 0-to-60 times to tumble. According to the Environmental Protection Agency’s 2022 Automotive Trends Report, the average American vehicle from model year 2021 could reach 60 mph in 7.7 seconds, which is about twice as fast as cars purchased in the early 1980s. That improvement was relatively consistent across sedans, SUVs, and pickups. As the Autopian, an automotive media outlet, recently observed, even a relatively plodding car “that accelerates to 60 in just over 8 seconds [wouldn’t] be a liability, anywhere.”

At this point, only Americans who race on a closed track would have a practical use for acceleration beyond what’s already on offer. Nevertheless, the incipient shift toward electrification is poised to give it to everyone, whether they want it or not.

Compared to internal combustion engines, electric powertrains contain fewer moving pieces while offering instant torque and electronic traction management. As a result, EVs are more efficient than gas-powered cars, and their acceleration is at another level, with 4- and 5-second 0-to-60 times common for even heftier models. “EVs can have very fast 0-60 acceleration times,” the EPA’s 2022 report noted, “and the calculation methods used for vehicles with internal combustion engines are not valid for EVs.”

In fact, Ezra Dyer wrote in The New York Times that EV buyers need not think about acceleration at all. “A quick electric car is as common as a sunny day in Los Angeles, a pleasant base-line normal that’s mostly taken for granted.”

But that hasn’t kept automakers from trumpeting their models’ 0-to-60 performance. In a 2022 tweet that begins “WOW, literally,” Chevrolet touted the sub-4-second 0-to-60 time of its Blazer SUV’s “Wide Open Watts Mode.” Why any SUV driver would need to accelerate that fast is a question left unanswered.

And then there’s Tesla, a company that has made scorching speed a centerpiece of its brand. The Cybertruck’s “Cyberbeast model,” for instance, can go from 0 to 60 in 2.6 seconds, less time than luxury gas-powered sports cars like the McLaren 720S (2.8 seconds), which costs more than $300,000. In 2021, Elon Musk boasted that the Tesla Model S Plaid was the “fastest production car ever” capable of reaching 60 mph in under 2 seconds. “The car feels like a spaceship,” he tweeted. “Words cannot describe the limbic resonance.”

Musk may find breakneck acceleration to be a transcendent experience, but for many EV passengers it’s a nauseating one. (“Drivers and passengers report motion sickness in EVs,” warned an ABC headline.) And, again, unless you’re racing on a closed track, it’s useless.

In fact, hyperfast EV acceleration is worse than a frivolous distraction; it could become a serious societal problem.

“A very powerful electric motor has no negative impact on efficiency and is only incrementally more expensive to produce,” The Smoking Tire’s Farah wrote. “What you DO need is a very big battery that can dump current quickly.” Such large batteries weigh more, which further fuels the ongoing enlargement of American automobiles, a phenomenon I call car bloat. Beyond requiring additional matériel to manufacture, bigger cars exert greater force in a crash and take more time to halt when depressing the brakes. The combination of acceleration and weight is especially concerning, since vehicles that burst forward at an intersection give those on the street scant time to get out of the way.

For all these reasons, heavy, lightning-quick EVs put other road users at risk—especially pedestrians and cyclists, whose deaths recently hit 40-year highs. Such EVs could be even more of a safety hazard than oversize gas-guzzlers, a danger that Jennifer Homendy, National Transportation Safety Board chair, has warned about.

And if that’s not bad enough, hyperfast acceleration—especially for heavy cars—shreds tires. Rapid tire erosion increases the cost of EV ownership, and it also generates tiny, toxic particles that waft through the air and wind up in streams and rivers, where they have caused fish die-offs.

Given the pointlessness and dangers of blazing acceleration, one might ask why automakers are dragging 0-to-60 times into an electrified era. Inertia seems to be an important part of the answer: It’s a metric that automakers and many car buyers are already familiar with, so why give it up—particularly when the basic design of EVs makes all of them seem so quick?

It’s true that emphasizing speedy 0-to-60 times might nudge undecided consumers toward electric models. But the allure would quickly dissipate, since the ultimate advantages of powerful acceleration are minimal, while its downsides—for car owners as well as society—are substantial.

Today’s car buyers would be wise to ignore the 0-to-60 metric entirely, even if automakers keep clinging to it.

“When I went to buy my own EV to commute around L.A., I bought the second-slowest version” of the Ford Mustang Mach E, said Farah, who frequently road tests sports cars. Although another version of the electric Mustang hit 60 mph in just 3.8 seconds, the one Farah chose takes almost 60% longer. “It’s as fast as I will ever realistically need to go,” he said. “And fast is what I do.”