- | 8:00 am

How gigantic solar farms of the future could change weather patterns around the world

It’s just a thought experiment, but researchers argue it’s an essential one.

The sun’s energy is effectively limitless. While resources such as coal or gas are finite, if you’re able to capture and use solar power, it doesn’t prevent anyone else from also using as much sunshine as they need.

Except that isn’t quite the full story. Beyond a certain size, solar farms become large enough to affect the weather around them and ultimately the climate as a whole. In our new research, we have looked at the effect that such climate-altering solar farms might have on solar power production elsewhere in the world.

We know that solar power is affected by weather conditions, and output varies through the days and seasons. Clouds, rain, snow, and fog can all block sunlight from reaching solar panels. On a cloudy day, output can drop 75%, while their efficiency also decreases at high temperatures.

In the long term, climate change could affect the cloud cover of certain regions and how much solar power they can generate. Northern Europe is likely to see a solar decrease, for instance, while there should be a slight increase of available solar radiation in the rest of Europe, the U.S. East Coast and northern China.

If we were ever to build truly giant solar farms that span whole countries and continents, they may have a similar impact. In our recent study, we used a computer program to model the Earth system and simulate how hypothetical enormous solar farms covering 20% of the Sahara would affect solar power generation around the world.

A photovoltaic (PV) solar panel is dark-colored and so absorbs much more heat than reflective desert sand. Although a fraction of the energy is converted to electricity, much of it still heats up the panel. And when you have millions of these panels grouped together, the whole area warms up. If those solar panels were in the Sahara, our simulations show, this new heat source would rearrange global climate patterns, shifting rainfall away from the tropics and leading to the desert becoming greener again, much as it was 5,000 or so years ago.

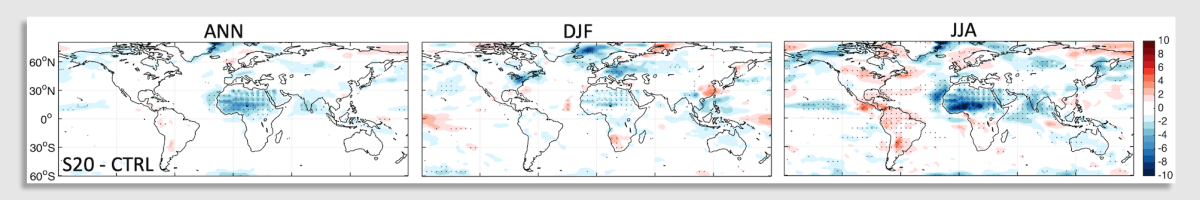

This would in turn affect patterns of cloud cover and how much solar energy could be generated around the world. Regions that would become cloudier and less able to generate solar power include the Middle East, southern Europe, India, eastern China, Australia, and the southwestern U.S. Areas that would generate more solar include Central and South America, the Caribbean, the central and eastern U.S., Scandinavia, and South Africa.

How global solar potential would be affected:

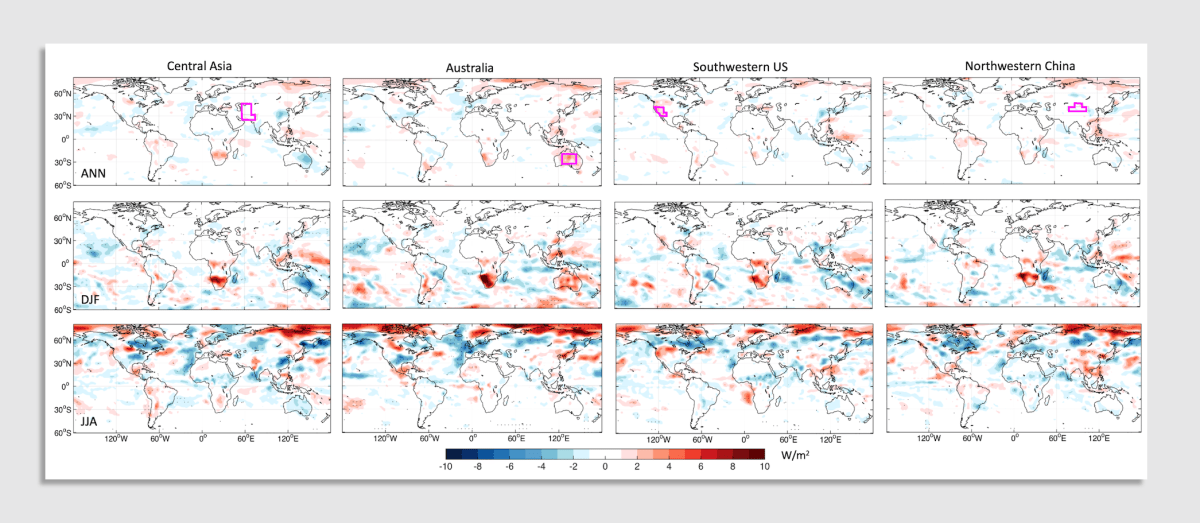

Something similar happened when we simulated the effects of huge solar farms in other hot spots in Central Asia, Australia, the U.S. Southwest, and northwestern China. Each led to climate changes elsewhere. For instance, huge solar farms covering much of the Australian outback would make it sunnier in South Africa, but cloudier in the U.K., particularly during the summer.

If huge solar farms were installed in other drylands:

There are some caveats. Things would shift only by a few percentage points at most; regardless of how much solar power we build, Scandinavia will still be cool and cloudy, Australia still hot and sunny.

And in any case, these effects are based on hypothetical scenarios. Our Sahara scenario was based on covering 20% of the entire desert in PV solar farms, for instance, and though there have been ambitious proposals, anything on that scale is unlikely to happen in the near future. If the covered area is reduced to a more plausible (though still unlikely) 5% of the Sahara, the global effects become mostly negligible.

WHY THIS THOUGHT EXPERIMENT MATTERS

In a future world in which almost every region invests in more solar projects and becomes more reliant on them, the interplay of solar energy resources can potentially shape the energy landscape, creating a complex web of dependencies, rivalries, and opportunities. Geopolitical maneuvering of solar project construction by certain nations may hold significant new power, influencing solar-generation potential far across their national boundaries.

That’s why it’s essential to foster collaboration among nations to ensure that the benefits of solar energy are shared equitably around the world. By sharing knowledge and working together on the spatial planning of future large-scale solar projects, nations should develop and implement fair and sustainable energy solutions and avoid any unintended risks to solar power production far away.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.