- | 9:00 am

How Google ditched plastic packaging

Google spent 3 years redesigning its packaging to eliminate plastic. Now, it’s releasing a guide so that other companies can do the same.

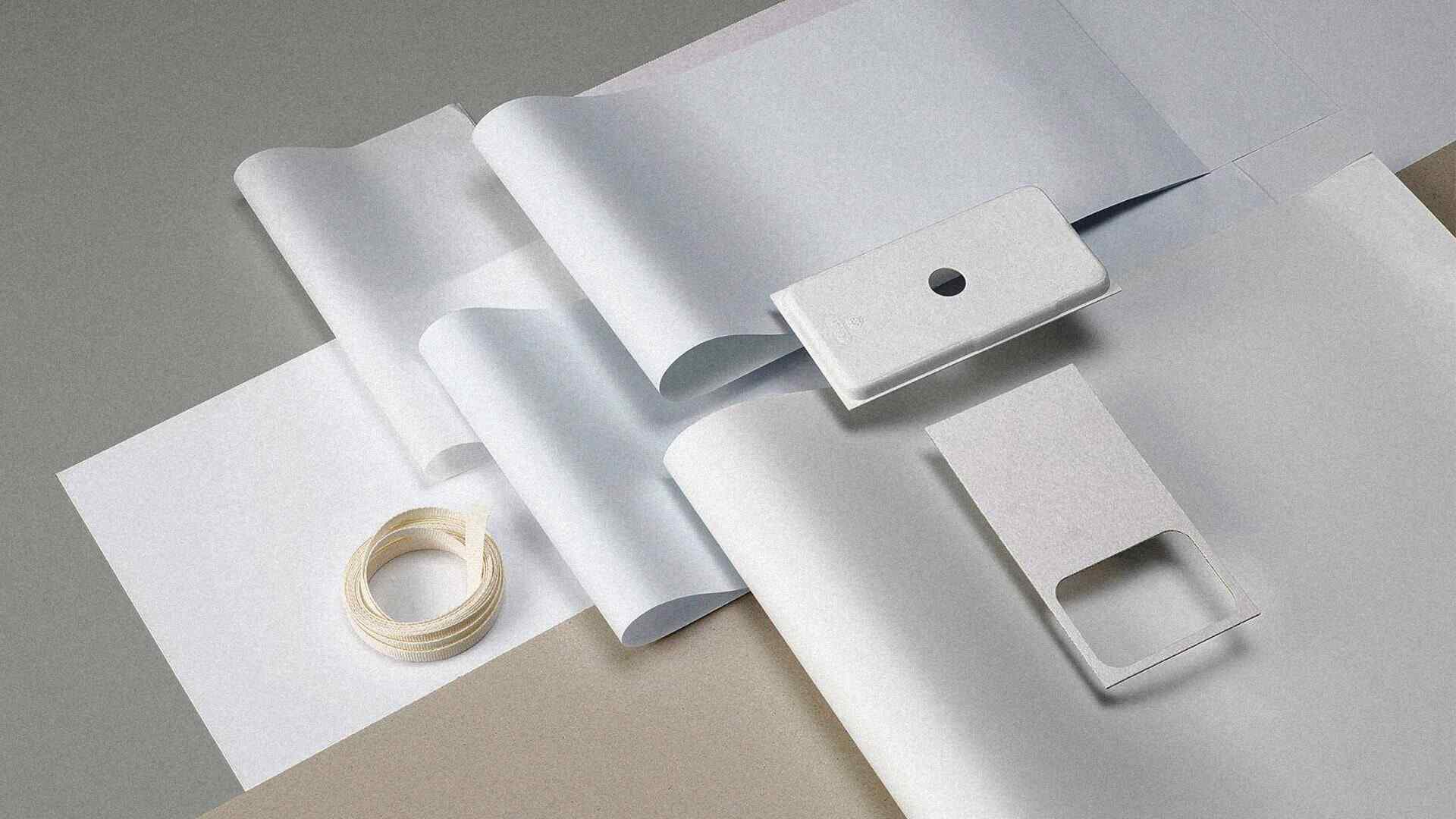

If you take a new Pixel 8 phone out of its package, you might not notice what’s missing. But there’s no plastic wrap around the box. There’s no plastic coating on the box itself. The labels that seal the box are now made from paper; so is the sturdy hangtag at the top of the box. Inside, the phone is cushioned by molded fiber instead of PET, and there’s no plastic cover over it.

The packaging is now completely plastic-free—just like every other Google electronics package will be in the future as new products launch. The redesign process took the company three years. Each step was a challenge; just replacing the plastic coating on the box took 12 months. Now, the packaging team wants to help other brands make the same switch.

It’s an attempt to begin to address the enormous challenge of plastic waste: Of the 19 million tons of plastic that leaks to the environment each year, the biggest chunk comes from packaging. Even if plastic packaging ends up at a recycling center—and most of it doesn’t—it often isn’t recycled.

“While many plastic materials can technically be recycled, the reality is for many material recovery facilities it is very operationally and economically challenging,” says David Bourne, lead for environmental strategy at Google. It’s especially difficult to recycle a package with mixed materials. The solution: ditch plastic entirely.

In a new guide, the team shares all of the details about the design changes they made, the materials they chose, and the suppliers they use, so other companies can copy the same steps. Without the information, another brand might spend years duplicating the work. “For another company with similar sustainability aspirations but fewer resources, that time horizon could be significantly longer,” says Miguel Arevalo, the company’s packaging sustainability lead. Here are the key steps the Google team took.

GETTING RID OF SHRINK-WRAP

Shrink-wrap is ubiquitous for a reason; it’s good at protecting boxes from damage and showing evidence of tampering. But it’s not necessary. “We believe that eliminating shrink-wrap is feasible for many product categories, especially in the consumer electronics industry,” says Bourne. The team made several changes to replace it. First, UV protective coatings protect the art from scratches. Strong fiber-based labels seal the box and show if it’s been opened. Last, since plastic wrap helps make the box stronger under pressure, the team redesigned the boxes to help strengthen them.

A NEW COATING

A typical electronics box has a plastic film coating that protects the paperboard from water or scratches and gives the box a glossy finish. But when it goes to a recycling center, the paper is harder to recycle. The plastic has to be separated and usually ends up in a landfill. Google tested multiple alternatives for performance, including how well the new coatings protected packages, how they performed at packing facilities and in shipping, and how easily they could be recycled, including “deinkability,” or how difficult it was to remove the printing on the package. The best alternative, from a company called Megami, can be recycled along with paper.

PAPER SEALS

Because Google wanted to stop using shrink-wrap, it needed to seal packages differently, and plastic seals can’t be recycled. The company found a paper alternative that was equally strong, but has other advantages, including the look and feel, “enhancing the overall unboxing experience,” says Arevalo. When the company tested the packaging with users, the paper seals were also easier to open. The guide explains in detail how the seals should be designed for different types of boxes.

PAPER TAPE AND HANG TABS

Hidden inside some boxes, Google used to use plastic tape to reinforce the corners for strength. It searched for a paper alternative that was equally strong, performed well in its suppliers’ machines, and was readily available in the supply chain. The paper tape they found can be recycled along with other paper. The company also found an alternative for the plastic tab at the top of the box that retailers used to hang it up. They tested a few approaches, but ended up using a molded fiber tab that performed like plastic and can be folded when the boxes are shipped.

INBOX TRAYS

In the past, the company used trays made from PET—the same plastic used in water bottles—to hold a phone securely inside a box. They put alternatives through another slew of tests, from how they protected the phone to how they worked at suppliers’ plants. The final choice was a molded fiber version that can be shaped to fit around a phone or other electronics precisely. Like other paper components, it also has a nicer feel and look than plastic, and can easily be recycled.

Making the full switch was a challenge—in some cases, replacing one part meant that other parts also had to change at the same time. The team also had to work closely with suppliers. “We sought out partners who demonstrated a willingness to adapt,” says Arevalo. “In some cases, this meant transitioning away from suppliers who were less able or willing to invest in new materials and processes. For example, finding a paper tape that met our strength and repulpability requirements involved extensive testing and collaboration with multiple vendors. We ultimately partnered with those who could provide the technical expertise and manufacturing capabilities needed to bring our vision to life.”