- | 9:00 am

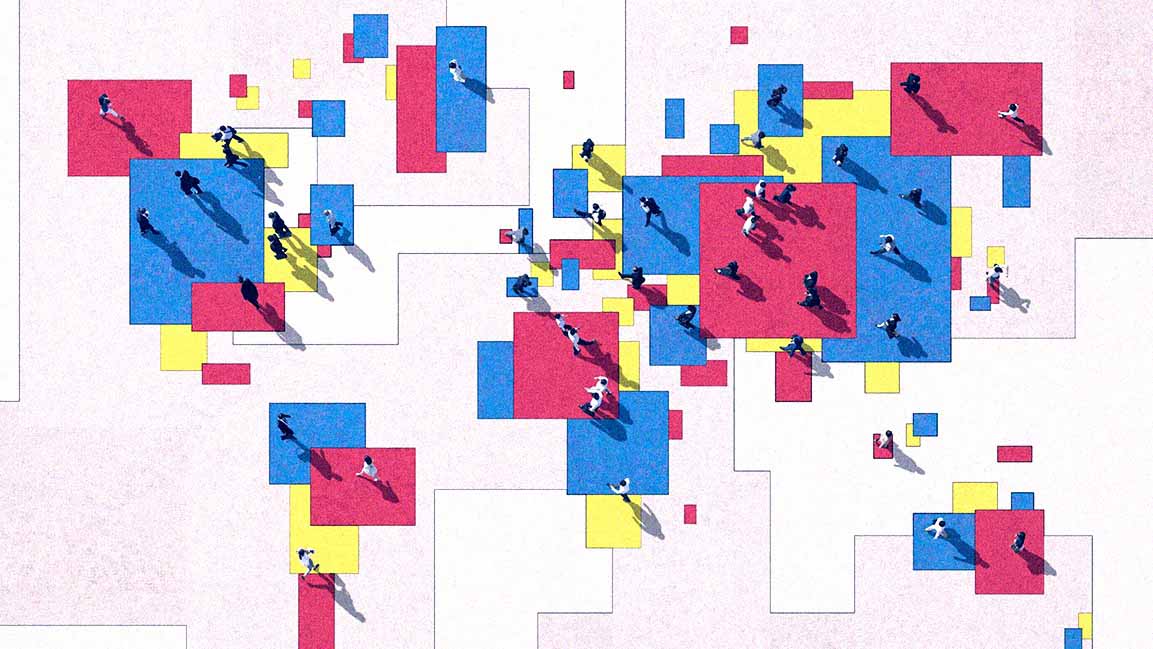

How the UAE’s built environment reflects multicultural identity

Leading architects, designers, and developers discuss the importance of inclusive design, its impact on both the form and function of spaces, and how it’s shaping the country’s urban landscape.

The UAE is home to one of the world’s most diverse populations. That diversity isn’t just visible in its communities; it is reflected in the globally recognizable skyline that celebrates the heritage and future aspirations of its residents.

The UAE’s built environment is a “living mosaic,” shaped by a design language that is both confident and authentically Emirati, says Christine Espinosa-Erland, Associate Director at Godwin Austen Johnson.

“We now see a mature dialogue between global perspectives and local narratives,” she says. “This convergence of cultures, ideas, and disciplines has created a rare ecosystem of creativity, where every project becomes a multicultural exchange rooted in the UAE’s vision, values, and sense of place.”

As the UAE accelerates major urban projects under long-term national strategies, inclusivity has shifted from a design philosophy to a practical necessity. The growth of multicultural communities, the demand for well-being-focused development, climate resilience, and the rise of hospitality-led living have all prompted architects and developers to rethink how spaces welcome and support people.

SHAPED BY COSMOPOLITAN VOICES

For interior designer Kadambari Uppal, Founder & Creative Director of KAD Designs, the UAE’s multiculturalism is both a catalyst and a benchmark, inspiring his team to transcend convention. “Every client brings their own story, cultural influences, and design sensibilities,” he says. “It pushes us to merge aesthetics and craftsmanship in unexpected ways.” The result is interiors that feel globally sophisticated yet emotionally resonant. “In many ways, Dubai’s cosmopolitan spirit mirrors our own: progressive, open-minded, and endlessly curious.”

Developers echo this shift toward culturally relevant design. Miltos Bosinis, CEO of H&H, says their projects are built for“global citizens united not by origin, but by values.” Developments such as Eden House Za’abeel and Eden House Al Satwa strike a balance between local character and international refinement, often incorporating materials and textures inspired by the surrounding neighbourhoods.

Collaborations with local artisans, he notes, enable H&H to reinterpret traditional techniques for contemporary living, sparking cultural curiosity while enhancing residential comfort.

At Qube Development, cultural relevance is a key metric. Marketing Director Asmae Boussouf highlights Arisha Terraces, where pergola-inspired architecture was used to shape how residents experience shade, privacy, and connection.“When a space is thoughtfully designed, it performs,” she says. “It resonates locally while appealing to a broad spectrum of buyers.”

DESIGNING FOR COMMUNITY AND WELL-BEING

A core aspect of this placemaking is ensuring that design supports community wellbeing. For Bosinis, this means creating environments where belonging emerges organically through communal spaces, wellness courtyards, social lounges, and shared workspaces that facilitate lasting relationships among residents. Hospitality-led services further strengthen this sense of ease. “The result is a community that feels both intimate and inclusive,” he says, one where locals and expatriates find familiarity and comfort.

For Qube, designing for well-being means prioritizing how people actually live. Arisha Terraces features hydroponic rooftop gardens, filtered drinking water, co-working zones, children’s play areas, libraries, wellness rooms, and cinema lounges. “A community only works when people feel seen, supported, and genuinely at home,” says Boussouf.

“Commercial success simply follows from getting the human experience right.”

This philosophy extends to technology, but only where it adds value. Boussouf emphasises that technology matters most when it fades into the background. “We use it to enhance clarity, comfort, and better living, not to complicate things,” she says, pointing to smart systems that intuitively regulate lighting, water, energy, and temperature.

A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO INCLUSIVITY

Elaborating on this approach, Uppal notes how a truly beautiful space functions effortlessly for the people who inhabit it.“Aesthetics and functionality are never separate; they evolve together,” he says.

Inclusive design, he adds, is built on emotional comfort, intuitive flow, and sensory balance. To address this, he says his firm’s in-house production capability allows them to customise details, as seen in a palace project in Ras Al Khaimah, where mashrabiya-inspired laser-cut screens, arched forms, and sculptural furniture combined contemporary comfort with subtle traditional influences.

Espinosa-Erland expands the definition further, emphasizing that architecture must nurture emotional and cultural connection as much as physical comfort. “That means designing for people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds,” she says, adding that true inclusivity means recognising that space is for everyone.

Collaboration is crucial to this goal. “No building stands alone. The most meaningful public spaces are born from dialogue between architects, artists, engineers, and communities. When artists shape the narrative, architects give it form, and communities infuse it with meaning, the result is shared authorship — spaces alive with identity and emotion. True placemaking is collective: environments belong to everyone because they were imagined by everyone,” says Espinosa-Erland.

THE PROCESS BEHIND INCLUSIVE DESIGN

Touching on the methodology and implementation, Espinosa-Erland also notes that inclusivity begins long before the first sketch is created. “It’s rooted in how we listen, observe, and understand who we’re designing for. Accessibility may be the foundation, but genuine inclusivity goes far beyond compliance; it’s about creating belonging.”

Inclusive design, she adds, is about welcoming people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds while responding to emotional and functional needs. “Design should be not only usable, but meaningful.”

Boussouf shares that this philosophy is highlighted in Elire, their branded residence, in their efforts to counterbalance the intensity of Business Bay. The internal flow creates moments of calm without disconnecting from the city’s energy, supported by mixed-use planning and flexible social zones. “Inclusivity isn’t a slogan,” she says. “It’s how we measure success five, ten, even 20 years after a project is built.”

WHAT INCLUSIVE DESIGN MEANS

Clearly, inclusivity means many things to many people, but at the core lies the value of belonging. “Good design should invite everyone in,” says Uppal. “Inclusivity begins with empathy — recognizing that homes and public spaces must welcome people of all backgrounds, beliefs, and lifestyles.”

Developers share this view. “The UAE has shown that social cohesion is not accidental, it’s intentional,” says Bosinis.“Real estate is not just a physical asset; it’s a framework for connection.”

As the UAE continues to evolve, inclusive design will shape cities that are not only visually iconic but emotionally intelligent, places where global communities find a sense of home that honours the past while embracing the future.