Plastic pollution is accumulating worldwide, on land and in the oceans. According to one widely cited estimate, by 2025, 100 million to 250 million metric tons of plastic waste could enter the ocean each year. Another study commissioned by the World Economic Forum projects that without changes to current practices, there may be more plastic by weight than fish in the ocean by 2050.

On February 28, 2022, a meeting of the United Nations Environment Assembly will open in Nairobi, Kenya. At that meeting, representatives from 193 countries are expected to consider a resolution that would launch negotiations on a legally binding global treaty to reduce plastic pollution. “[N]o country can adequately address the various aspects of this challenge alone,” the draft resolution states.

I am a legal scholar and have studied questions related to food, animal welfare, and environmental law. My forthcoming book, “Our Plastic Problem and How to Solve It,” explores legislation and policies to address this global “wicked problem.”

I believe plastic pollution requires a local, national, and global response. While acting together on a world scale will be challenging, lessons from some other environmental treaties suggest features that can improve an agreement’s chances of success.

A PERVASIVE PROBLEM

Scientists have discovered plastic in some of the most remote parts of the globe, from polar ice to Texas-size gyres, in the middle of the ocean. Plastic can enter the environment from a myriad of sources, ranging from laundry wastewater to illegal dumping, waste incineration, and accidental spills.

Plastic never completely degrades. Instead, it breaks down into tiny particles and fibers that are easily ingested by fish, birds, and land animals. Larger plastic pieces can transport invasive species and accumulate in freshwater and coastal environments, altering ecosystem functions.

A 2021 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine on ocean plastic pollution concluded that “[w]ithout modifications to current practices . . . plastics will continue to accumulate in the environment, particularly the ocean, with adverse consequences for ecosystems and society.”

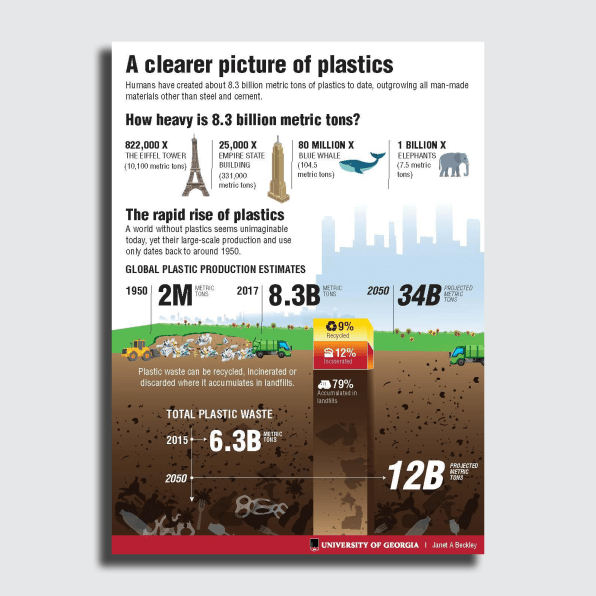

Plastic pollution by the numbers. [Image: University of Georgia/CC BY-ND]

NATIONAL POLICIES ARE NOT ENOUGH

To address this problem, the U.S. has focused on waste management and recycling rather than regulating plastic producers and businesses that use plastic in their products. Failing to address the sources means that policies have limited impact. That’s especially true since the U.S. generates 37.5 million tons of plastic yearly but only recycles about 9% of it.

Some countries, such as France and Kenya, have banned single-use plastics. Others, like Germany, have mandated plastic bottle deposit schemes. Canada has classified manufactured plastic items as toxic, which gives its national government broad power to regulate them.

In my view, however, these efforts too will fall short if countries producing and using the most plastic do not adopt policies across its life cycle.

GROWING CONSENSUS

Plastic pollution crosses boundaries, so countries need to work together to curb it. But existing treaties, such as the 1989 Basel Convention, which governs international shipment of hazardous wastes, and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, offer little leverage, for several reasons.

First, these treaties were not designed specifically to address plastic. Second, the largest plastic polluters—notably, the U.S.—have not joined these agreements. Alternative international approaches, such as the Ocean Plastics Charter, which encourages governments and global and regional businesses to design plastic products for reuse and recycling, are voluntary and nonbinding.

Fortunately, many world and business leaders now support a uniform, standardized, and coordinated global approach to managing and eliminating plastic waste in the form of a treaty.

The American Chemistry Council, an industry trade group, supports an agreement that will accelerate a transition to a more circular economy that promotes waste reduction and reuse by focusing on waste collection, product design, and recycling technology. America’s Plastic Makers and the International Council of Chemical Associations have also made public statements supporting a global agreement to establish “a targeted goal to ensure access to proper waste management and eliminate leakage of plastic into the ocean.”

However, these organizations maintain that plastic products can help reduce energy use and greenhouse gas emissions—for example, by enabling automakers to build lighter cars—and are likely to oppose an agreement that limits plastic production. As I see it, this makes leadership and action by governments critical.

The Biden administration also has stated its support for a treaty and is sending Secretary of State Antony Blinken to the Nairobi meeting. On February 11, 2022, the White House released a joint statement with France that expressed support for negotiating “a global agreement to address the full life cycle of plastics and promote a circular economy.”

Early treaty drafts outline two competing approaches. One seeks to reduce plastic throughout its life cycle, from production to disposal—a strategy that would probably include methods, such as banning or phasing out single-use plastic products.

A contrasting approach focuses on eliminating plastic waste through innovation and design—for example, by spending more on waste collection, recycling, and development of environmentally benign plastics.

ELEMENTS OF AN EFFECTIVE TREATY

Countries have come together to solve environmental problems before. The global community has successfully addressed acid rain, stratospheric ozone depletion, and mercury contamination through international treaties. These agreements, which include the U.S., offer strategies for a plastics treaty.

The Montreal Protocol, for example, required countries to report their production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances so that countries could hold each other accountable. As part of the Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution, countries agreed to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions, but were allowed to select the method that worked best for them. For the U.S., that involved a system of buying and selling emission allowances that became part of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990.

Based on these precedents, I see plastic as a good candidate for an international treaty. Like ozone, sulfur, and mercury, plastic comes from specific, identifiable human activities that occur across the globe. Many countries contribute, so the problem is transboundary in nature.

In addition to providing a framework for keeping plastic out of the ocean, I believe a plastic pollution treaty should include reduction targets for both producing less plastic and generating less waste that are specific, measurable, and achievable. The treaty should be binding but flexible, allowing countries to meet these targets as they choose.

In my view, negotiations should consider the interests of those who experience the disproportionate impacts of plastic, as well as those who make a living off recycling waste as part of the informal economy. Finally, an international treaty should promote collaboration and sharing of data, resources, and best practices.

Since plastic pollution doesn’t stay in one place, all nations will benefit from finding ways to curb it.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.