- | 12:56 pm

The company behind this bottle wants to upend the Earth-destroying, $60 billion palm oil business

C16 Biosciences CEO Shara Ticku’s audacious vision to bio-manufacture a palm oil alternative could forever change the food and personal care industries.

Sodium laureth sulphate. Sodium lauryl sulphates. Glyceryl stearate. Cetyl palmitate. Palm kernel oil. If you take even a few minutes to read the labels on the products in your pantry and bathroom—from peanut butter to sunscreen—you’ll see these ingredients (and many other similar-sounding ones) over and over again.

Guess what? As the Rainforest Action Network (RAN) observed way back in 2011, they’re all palm oil. “It’s in half of all consumer goods,” says Emma Rae Lierley, a RAN spokesperson. “It’s one of the most widely used vegetable oils on the planet.”

[Photo: richcarey/iStock/Getty Images Plus]

[Photo: courtesy C16 Biosciences]

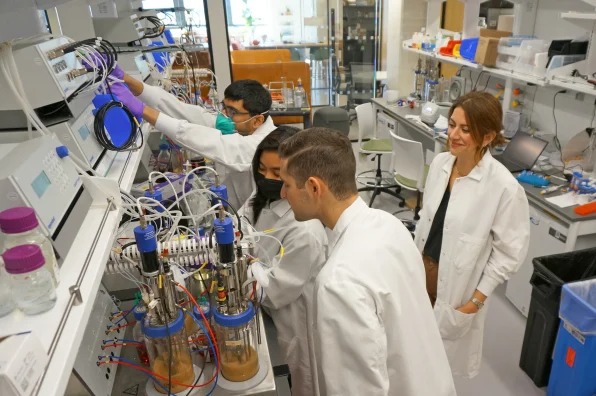

So it’s a mesmerizing experience to stand in a biotech laboratory located about as far west in Manhattan as you can be without walking into the Hudson River and watch four glass cylinders oscillate with a liquid the color of ripe papaya and the viscosity of a smoothie. This miniature reactor is bio-manufacturing a palm oil alternative, the first product from the startup C16 Biosciences. A particular strain of yeast that produces oil from eating a sugar or another feedstock can do in seven days what a mature palm tree needs seven years to achieve.

The potential for this biotech breakthrough is profound. “Palm oil has the biggest breadth of application because it’s not really one product. It can span the spectrum of oil and fat needs,” says Shara Ticku, C16’s cofounder and CEO. “It has really good performance properties,” from ensuring that Tide detergent is shelf stable to giving Nutella its perfect spreadability. “It’s just really good at what it does.” From the shake flasks vibrating in what looks like a dishwasher rack to the chemistry lab extracting the crude oil out of cells, C16 can run experiment after experiment to refine its process and tailor its products to customer needs—all of it presenting an alternative to deforestation and the further exacerbation of the devastating effects of climate change.

[Photo: courtesy C16 Biosciences]

C16 Biosciences cofounder and CEO Shara Ticku [Photo: courtesy C16 Biosciences]

A RELUCTANT ENTREPRENEUR

From the time Ticku was a child, she wanted to be a doctor. Whenever anyone would ask about her career aspirations, “My answer was always a neurologist,” she says, “because my father was a neuropharmacologist. So I knew what that word was.”

Growing up in San Antonio, Ticku was the kind of high achiever who was admitted into the University of Texas at Austin’s Plan II Honors Program, but she gravitated to UT’s business program because it was a more “tangible degree,” she says. Her first job took to her Wall Street, and as she dubs it, “the heart of capitalism”—the sales and trading floor at Goldman Sachs.

While she expresses her love for many aspects of that job, it also led to what she calls her quarter-life crisis. “This is a great company. I love my team. It’s fun. I like my clients. I just don’t really care about public equity markets,” she says. “I was 24, and I asked myself, Does that matter? What does work mean to me? The thing that I kept coming back to was life sciences broadly and healthcare specifically. I was this close to going to med school after Goldman, but I decided to go more broad for healthcare.”

Ticku spent two years working for the Clinton Health Access Initiative, where she focused primarily on sexual and reproductive health, helping women secure medicines that they did not have previously by working with drug manufacturers, multinational companies, and governments to solve what she calls “the market failure of healthcare.”

This work, while also rewarding, came with its costs. “I was on a plane to Africa every two to three weeks, and on, like, a 30-hour route,” she says, but beyond the personal toll, there was also a revelation. “I was focusing my efforts on lower- and middle-income countries, and I realized, what are we doing here telling these countries how to run their healthcare systems when our healthcare system is pretty darn broken? And it’s a $17 trillion industry. . . . That’s what led me to business school in Boston.” (Ticku has that self-effacing tic that many highly-credentialed people do of always burying her achievement in a generality: In fact, she went to Harvard Business School.)

Boston was a great place for Ticku to explore the question she had going into her MBA studies: “Why is there so much innovation that happens in academic research labs, especially in biology labs, that doesn’t get commercialized?” she asks. “What are the levers that we can pull to elevate that?”

This is what led her to the MIT class where she met Heller and McNamara, and the idea of “commercializing wacky, moonshot science. When does it work and when does it not? What’s so hard about it and how can we do more of it?” She admits that, going into Revolutionary Ventures, she was not thinking of starting a company. “I would actually have considered myself quite risk-averse at the time,” she admits.

Ticku, Heller, and McNamara explored the idea that became C16—the name comes from the 16-carbon fatty acid that is a significant palm oil component—for about a year and a half before making the commitment in 2018 to incorporate and go for it. “We had done enough of the science,” she says, “to believe that there’s a there there.” Later in our conversation she adds, “One of the things that I think helped compel us to take the leap was one of the first customer conversations I had. A company had a product that they were going to [make for Whole Foods’s 365 store brand], and Whole Foods said, we love this product but you have to take palm oil out of the formulation. We cannot launch a product in 365 if it’s got palm oil. That was a compelling signal.”

TAKING ON BIG PALM

The audacity of C16’s pursuit has inspired a litany of armchair commentary from its earliest days. “A lot of people told us that we were fools or much worse,” Ticku says, “and that we had no shot at solving this problem, but good luck to you.” Even if people did believe in the idea, they questioned Ticku’s strategic decisions. I bring up the 2019 Harvard Business School case study on C16, which more than seemed to suggest that Ticku was making a mistake by pursuing the personal care market first rather than food.

“Every decision [we make] is fundamentally rooted in, What is our best shot at solving this problem at scale?” Ticku says. “The HBS case study sort of lays out this question, which is, ‘Well, if you want to solve this problem at scale, go after the largest market, right? Obviously.’ Not obviously.”

As Ticku notes, she is going up against an entrenched industry with a lot of advantages, including both economies of scale and significant momentum. Palm oil production has grown from 2 million tons in 1970 to more than 70 million five decades later. The FDA’s 2015 ruling against the use of artificial trans fats in foods further spiked demand for palm oil because of its versatility.

“There are always going to be folks that second guess,” says Peter Turner, a partner at Breakthrough Energy Ventures, which invested in C16’s Series A in 2020 when the company was eight people operating in an office about the size of a conference room. “But Shara absolutely has chosen the right path by pursuing personal care first,” says Turner. He marvels at C16 being able to have a commercial product in its Palmless oil before raising a Series B.

For Ticku, the way to achieve the company’s goals has always been about “getting a product in market fast, proving that you can be profitable—fast—and using all of that to funnel back into the company to invest in further scale and lowering cost over time, which go hand in hand,” she says. “That is going to tee us up for success, so much more than trying to chase the very big market, which is, funnily again, fundamentally a game of large scale, low cost.”

Environmental groups are intrigued by how lab-produced palm oil alternatives bring more attention to the problems in the palm industry but remain circumspect that they’re the answer. “These innovations are interesting, but we shouldn’t be distracted by the prospect of a ‘technical fix’ to solve the urgent problem of the current environmental and social impacts of palm oil production,” says Grant Rosoman, a Greenpeace International senior advisor. “For the next few years at least, these products are likely to remain niche, due to the complicated nature of the processes involved. They will struggle to compete on price with natural palm oil and so are not expected to supply a substantial proportion of global consumption.”

[Photo: courtesy C16 Biosciences]

C16 may be focused at present on meeting the demand for its $45 nourishing oil, which sold out immediately when it first went on sale in March, as well as its opportunity to be a player as a branded ingredient in the beauty and personal care space. As Ticku says, it is projected to be an $800 billion industry this year.

But the company is also actively exploring replacing palm oil in food products. Tucked in the back of its New York laboratory is what at first glance appears to be a sad office kitchen. Inside the messy refrigerator are the kind of round plastic containers that one might usually see holding a generous side of tzatziki sauce in a takeout order from that great falafel joint in your neighborhood, but they are filled with C16’s formulations of various grocery store staples as well as samples of those legacy products. A sliced bagel in a plastic zip bag sits on the door ready to be called into service as the delivery vehicle for the experiments conducted here.

“This room is dedicated to product development,” says Ticku’s cofounder Heller, who oversees operations, during my lab tour. “We’re testing out the impact or the effect that our oil has compared to, say, palm oil or other vegetable oils in a number of different food products. Butters, cheeses, plant-based meats—all sorts of products that are really heavily reliant on fats, the texture and consistency of fats, to be able to function properly.” As Breakthrough Energy’s Turner notes, “Fats are such a strong component—on a sensoric level, how they cook, and calorically—of alternative proteins.”

[Photo: courtesy C16 Biosciences]

Ticku’s career experiences up to this moment have served her well. Turner describes her “phenomenal job navigating” the headwinds presented by COVID-19 and the market. Her grounding in the macro economy from her time on Wall Street has also helped her set up C16 to be a trusted supplier to brands and retailers thinking about reshoring aspects of their supply chains and guaranteeing their supply of essential ingredients in an increasingly fraught geopolitical climate. “There are forces, which include regulation—like the EU’s recent deforestation law—retailer pressure to change supply; and then there’s this inherent incentive, whether at the government level or at the corporate level, to take more control and bring in house to some extent, your supply chain,” she says, “that make this a compelling business.”

But those tailwinds, as important as they are, only matter because, as Ticku says, “we’re betting on this business succeeding because the product is compelling.” And it is.