- | 8:00 am

These plastic-eating bacteria can turn trash into silk

Scientists developed a new process that tackles two problems at once—what to do with existing plastic waste and how to make new materials that are more sustainable.

In a landfill, a plastic bottle can take more than a thousand years to break down. But a new process can transform polyethylene plastic in days, using bacteria to eat the waste and then turn it into a biodegradable material inspired by spider silk.

The system, developed by researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI), is designed to tackle two problems—both having to deal with existing plastic waste and how to make new materials that are more sustainable. Of the hundreds of millions of tons of plastic produced globally every year, the vast majority isn’t recycled. Polyethylene plastic, found in single-use food packaging, is especially likely to end up in landfills or the environment, degrading into tiny pieces that can end up in beer and breast milk. Producing new plastic from fossil fuels also has a huge carbon footprint and adds to the pile of waste.

To develop the new approach, the scientists turned to bacteria that are naturally able to consume polyethylene. Then they genetically edited the microbes so that they could also produce a silk-like material, by inserting a sequence of amino acids similar to a protein found in silk.

“What we’re using is a process that’s very similar to brewing beer,” says Helen Zha, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at RPI and one of the authors of a new paper about the project. “It’s essentially fermentation.” Instead of feeding the microbes sugar, like a brewery would, the researchers feed them a “predigested” form of plastic waste that’s been heated under pressure. When the bacteria eat the plastic, they use the carbon in it to make the new material.

The same process could be used to make other materials, but the scientists wanted to begin with silk because of its unique properties: Silk can be both very strong and lightweight, and it’s naturally biodegradable. “It functions like a plastic that we’re used to, in many ways, and it also breaks down very naturally even if we don’t treat it in some special manner,” she says. “We don’t have to worry about microplastics from silk, or Pacific garbage islands floating around with silk.”

Natural silk is already used in some applications beyond fabric, including as an ingredient in skincare products or to make medical products like surgical dressings. But the traditional production process isn’t sustainable, since it involves a lot of land, water, and fertilizer to grow food for silkworms. (It also isn’t vegan, as the silkworms are killed.) It can’t scale up easily, since it takes time to raise the silkworms and for them to produce cocoons. Spiders aren’t farmed for silk because the process would be even less efficient.

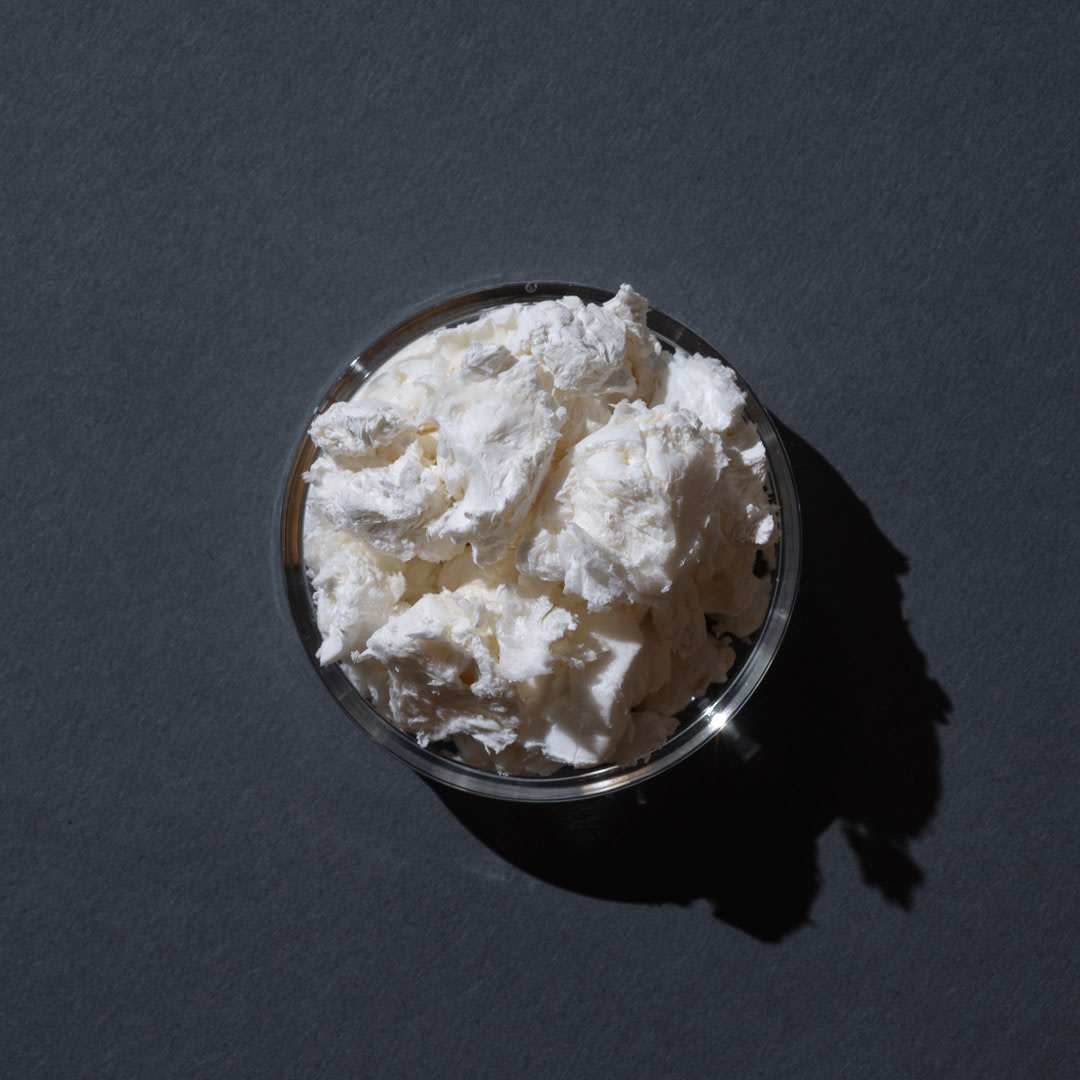

If silk were brewed from plastic instead, it could potentially be used more widely, making items like plastic wrap, which can’t be easily recycled now. “It’s a protein, so you could actually eat it if you want to,” says Zha. If it ended up in a landfill or littered in nature, it would break down, unlike some forms of “biodegradable” plastic that degrade much more slowly if they’re not processed in an industrial-composting facility.

Using gene editing means that it’s also possible to adjust the material, looking to inspiration from the types of silks made by different types of spiders (a single spider by itself can make seven different types of silk). “One of the benefits of working with an engineered organism as opposed to an actual spider or an actual silkworm is we can control very precisely the amino acid sequence of the protein that we make,” Zha says. “And that means we can also start to control and tune the properties of the resulting material.” A silk ingredient used in cosmetics might be engineered to hold onto water and break down easily, for example, and silk used to make a nylon-like material for clothing might be tweaked to be stretchier and longer-lasting.

So far, the scientists have demonstrated a proof of concept, showing for the first time that bacteria can make a valuable material by feeding on plastic waste. Now, the team is working to make the process more efficient so that the bacteria can produce more material. While it will take more R&D, Zha says that she’s optimistic that the yields can improve to the point where production could become commercially viable.

Others are also working on ways to use biology to deal with plastic waste. Carbios, a French startup, uses an enzyme that was originally discovered eating PET plastic in compost, tweaking it so it can break down plastic faster at higher temperatures. After this “enzymatic recycling,” the molecules can be used to make new plastic in a closed loop. The company plans to open its first large-scale recycling plant next year.

But turning plastic into a biodegradable material, instead, could be even more useful. The basic approach could help transform manufacturing. “Instead of big chemical plants, with really nasty chemicals and high temperatures making plastics for us,” says Zha, “nature could make the materials we need with the properties we need, at fairly low temperatures. And that material could be useful, and not pollute the planet in the long term. To me, that is the kind of future that we should be striving for.”

Correction: The process is designed to work with polyethylene plastic, not polyethylene terephthalate (PET).