- | 8:00 am

Trucks and SUVs keep getting bigger. Here’s how they should be redesigned to be less deadly

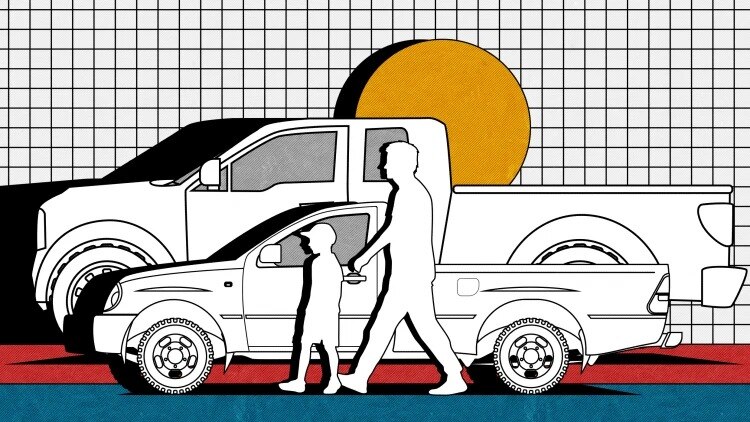

Pickups and SUVs have become bigger and heavier over the past two decades—which raises the likelihood that pedestrians will die in a collision with one of them.

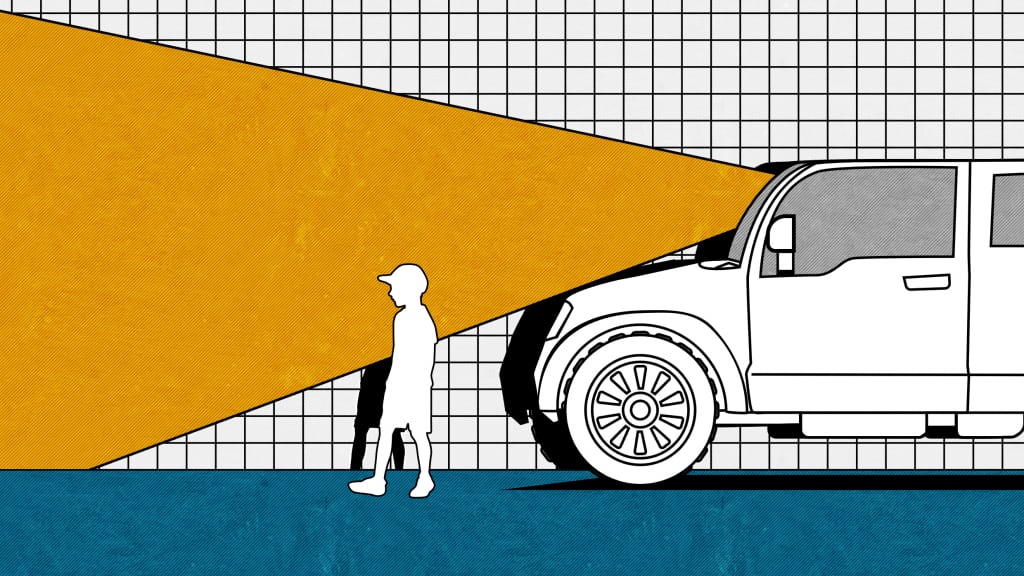

Crossing the street in front of a gigantic modern pickup truck feels like an act of bravery—because it is: It’s rarely clear whether the driver can actually see you. As SUVs and trucks have gotten bigger—the average pickup got 11% taller and 24% heavier between 2000 and 2018—they’ve also become deadlier. A study looking at six years of crashes found that pedestrians were 68% more likely to die if they were hit by a pickup than a car; full-size SUVs make death 99% more likely. It doesn’t help that Americans have abandoned smaller sedans, so there are many more large vehicles on the road.

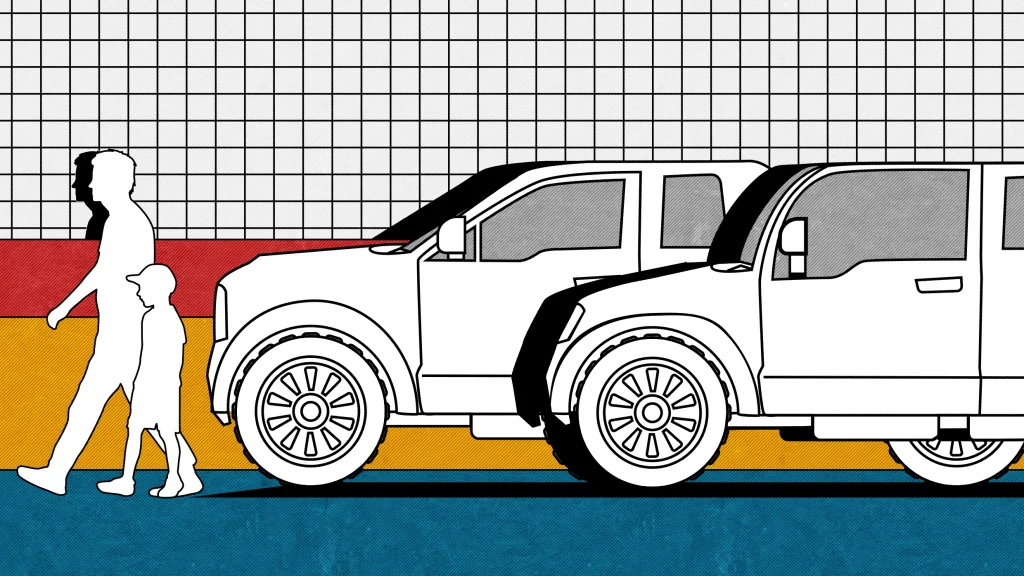

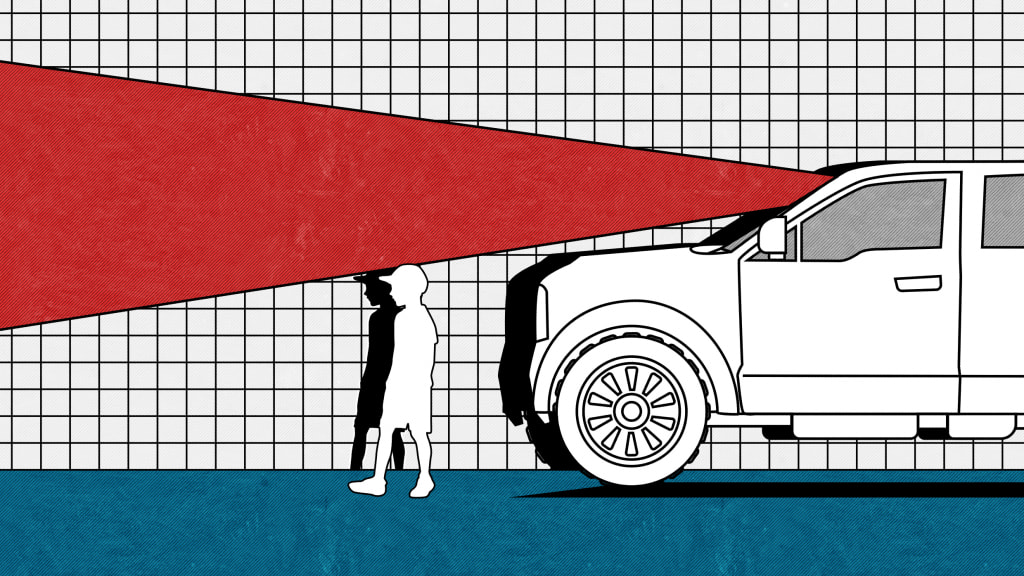

In Paris, the mayor has proposed banning oversize vehicles. But while they’re still on the road elsewhere, some design changes could help. As one step, front ends and grilles should be much lower: pickups and SUVs with a hood height taller than 40 inches are more dangerous than those with a hood height of 30 inches or less, according to a study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. If someone’s hit by the vehicle, a lower front end makes it more likely that they’ll be hit in the legs rather than in the head or in the vital organs in their torso, meaning it’s more likely that they’ll survive.

The shape of the front end also matters. A flat, blunt grille is more dangerous than one that slopes. “It’s called blunt-force trauma for a reason,” says Ben Crowther, policy director for the nonprofit America Walks. The IIHS study found that even in vehicles with hood heights lower than 40 inches, a flat, vertical front increased risk to pedestrians in a crash by 26% compared to a traditional sedan.

The U.S. Postal Service’s new delivery truck is a good example of how to design a large vehicle safely, Crowther says. “It has a rounded front end, and the lower part of the front end is really low to the ground,” he says. “It decreases the likelihood that someone can get swept under that vehicle when they’re hit.” (The aesthetics of the duck-like delivery truck are arguably another issue: Designers have to figure out how to make vehicles both look good and be less deadly.)

Pickups, vans, and SUVs can also be designed for better visibility. “Right now, the combination of taller vehicles and obstructing A-pillars—the supports for the roof and windshield—make it so that drivers have a hard time seeing people in front of them, especially when turning,” says Crowther. While some delivery vehicles have been redesigned to change this, passenger vehicles need to follow that example, he says.

Better technology can also help, including controversial speed limiters that sense a vehicle’s location and automatically throttle the engine if a driver is speeding. Europe already requires the tech on new vehicles, and California’s legislature passed a similar law, though Governor Newsom vetoed it. “It’s a completely realistic expectation that drivers should adhere to legal speed limits,” Crowther says.

Until now, the federal New Car Assessment Program’s safety tests have only looked at the safety of people inside a vehicle—not how a vehicle’s design impacts people walking or biking next to it. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration just adopted a new rule that requires the tests to include pedestrians. That might help nudge manufacturers a little, though the program isn’t mandatory—it’s meant for consumer information. And the new pedestrian data will be reported in a separate category, so car buyers may never see it unless they specifically seek it out. “A car could still get five stars for safety and fail that pedestrian crashworthiness test,” says Crowther.