- | 9:00 am

What’s fueling the surge in MENA’s fractional property ownership market?

Experts say owning a fractional interest in a property allows people to invest smaller amounts and earn returns.

Nasr and four members from his community signed up to co-invest in an apartment in New Cairo, an upscale area in the east of the city. The unit, part of an off-plan development project, is priced at an estimated EGP 5 million ($106,000) and is scheduled for completion by 2030.

“It is the only way I can invest in property,” says Nasr. “Real estate prices are very expensive, and without sharing the cost with others, I wouldn’t be able to afford it.”

The six-year payment plan also makes it accessible to Nasr, giving him a lower entry point into the Egyptian real estate market than he would otherwise have.

Since he is co-investing informally, without signing up with a fractional property ownership company, he is relying on the trusted relationships with his other four investors. “We have an agreement that we will sell the unit once completed, and we will each take our fair share of the property,” he says.

Interestingly, companies offer investors the opportunity to purchase property shares in booming cities such as Cairo, Dubai, and Riyadh. What was once a traditional sector that required large sums of money to enter, either through bank loans or access to wealth, is now being digitized and made accessible to smaller or more risk-averse investors.

WHY IS IT APPEALING

In Cairo, leading proptech company Nawy launched Nawy Shares, its fractional property ownership arm, to give investors the opportunity to own shares in some of Egypt’s premium real estate projects, starting as low as 5 percent in off-plan units.

Launched three years ago as a pilot program for its employees, Nawy Shares quickly grew to reach investors nationwide. “The units would literally be sold within hours after the email was sent out,” says Abdel Azim Osman, co-founder of Nawy.

He likens it to when Apple releases a new iPhone, and people line up to buy the latest version. With Nawy Shares, properties would often be sold a few hours after being announced on the platform. “We started with our own employees, we then opened it up as invite-only, and then we started opening it up to other startups with whom we had relationships. That’s how it started to grow until eventually, maybe a year ago, we opened it up to the market.”

To date, the platform has 270,000 users and has sold properties valued at EGP 5.2 billion, or $110 million.

The reason for the concept’s appeal, according to Osman, is that real estate is generally the preferred asset class for investors. It also typically requires the most upfront capital. Yet, owning a fraction or share of property gives people the opportunity to invest smaller amounts of money and make returns.

“When we look at our data, properties, especially premium properties, appreciate much faster than non-premium properties,” explains Osman. “Real estate is very well hedged against currency risk, and when we look at the averages, generally it will move one-to-one with the currency. It might lag a bit, but generally it will always catch up, and if you’re picking the right properties, then it exceeds the increase in currency, but people are not buying real estate because they can’t afford it.”

HOW IT WORKS

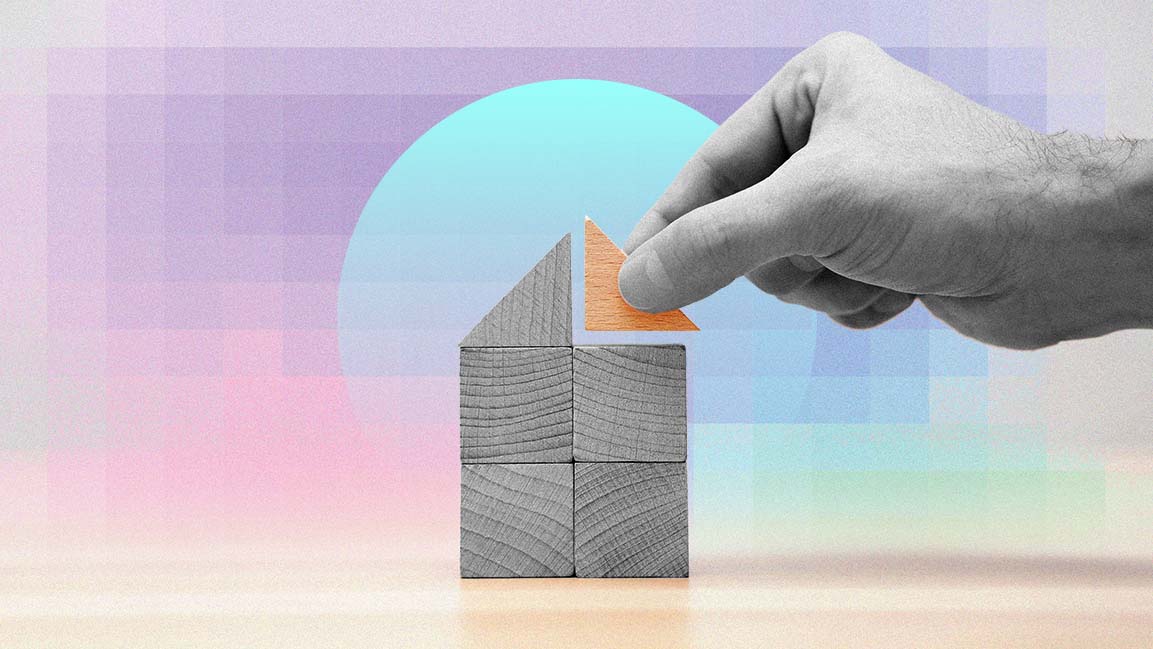

Emerging as an alternative to traditional property ownership, fractional property ownership involves multiple investors owning shares or fractional interests in a property.

For Nawy, there’s no limit or cap on the number of investors per property. Its main requirement is that no investor holds a majority of the shares. Since the company currently deals with off-plan projects, its aim is to provide returns to investors on the amounts they have paid. Typically, investors pay about EGP 5,000, equivalent to $100 per month.

When it comes time to exit, Nawy returns the investment plus the appreciation. “We’ve had exits on units where we bought the property within three months,” he explains. “We were able to return double what that person paid. There is an exit clause in the contract between the investor and me saying that if I’ve reached above a certain percentage, I can terminate the contract, return your money, plus the appreciation there minus my fee.”

While Nawy focuses on offline units, Stake, a fractional property-ownership startup in the UAE and, more recently, Saudi Arabia, works with on-site real estate. To date, it has about 600 properties on its platform. Rami Tabbara, co-founder of Stake, explains that anyone can invest in Dubai properties. All they need is $150.

“It’s a very simple process,” Tabbara says. “You download the app, create an account, upload the necessary documents, and choose which property you want to invest in using a debit card or a bank transfer. You invest in it starting from AED500, and then you start earning income at the end of every month equal to how much you’ve invested.”

He adds that the investor receives two documents as proof of ownership. One is a title deed in the name of a company that’s set up to own the property. The other is the share certificate, which is the investor’s ownership in the company that owns the property.

INVESTMENT RISKS

Like any investment, however, fractional property ownership comes with risks.

The main one is that real estate investing can be volatile, depending on market conditions. Although real estate has proven to be more stable than other investment instruments and is generally perceived as the primary go-to asset class in the region, it can still be risky. “I think the same risks apply when you’re investing in a property on your own or with a platform like Stake,” explains Tabbara. “The market can potentially drop, and the prices will then eventually take a hit, similar to any other asset class.”

Another concern for investors is exits. Unlike stocks or even crypto, where investors can exit on the spot, fractional property ownership has set exit windows. For Stake, investors can exit twice a year. “Real estate is a long-term investment, and we highlight that to our investors,” says Tabbara. “When you’re buying real estate, there are certain fees associated with it. There are government fees, there are broker fees, etc. So, in order to amortize that, you need to hold the real estate or your investment for a longer term.”

Regardless of inherent risks, however, Stake is seeing a growing appetite on its platform. The startup has more than 2 million users and has paid an estimated AED60 million in rent.

In 2024, it also entered Saudi Arabia just as the country was opening its property market to foreign ownership. “In our first year, we transacted under SAR500 million (about $133 million), and from these investors, over 30 percent of those were international investors.”

As people look to hedge against inflation and economic volatility, Osman expects investors to increasingly adopt fractional property ownership and include it in their portfolios. However, he recommends having diversified investments. “You should diversify your portfolio, and that way you protect yourself against any swings,” he says.

Meanwhile, Nasr is eager to see returns on his investment when it comes time to sell the property. “I’ll look forward to the day when we finally sell. I hope it will be a good investment for my family and me.”