- | 9:00 am

Why fruit flies could hold the secret to scaling up lab-grown meat

Future Fields developed a new process that could help the cultivated meat industry lower sky-high production costs and meet surging demand.

It’s a familiar sight most of us have dealt with: a swarm of fruit flies circling around an old banana peel you forgot to discard or an overripe apple lingering in the fruit bowl.

While the pests are a nuisance in the home, in the lab they could help the cultivated meat industry lower sky-high production costs and meet surging demand. A Canadian company is using fruit flies as a growth medium to produce recombinant proteins, a key raw material in lab-grown meat. The system is designed to replace the current method of protein production, offering a way that’s cheaper, more sustainable, and easier to scale.

Many cultivated meat companies use recombinant proteins, which are growth factors that stimulate animal cells to thrive when outside of the actual animal’s body. These proteins aren’t edible parts of the final product; rather, their job is to signal to the animal cells to proliferate, allowing these companies to produce the high volumes of meat that they need.

But making recombinant proteins can be complex. They’re essentially manipulated forms of proteins developed by inserting desired genetic material into host cells—such as animals, yeast, or bacteria—and instructing them to produce the protein in large quantities.

“Basically, you’re hijacking the organism’s cellular machinery to produce a protein product,” says Matt Anderson-Baron, cofounder and CEO of Future Fields, based in Edmonton, Alberta.

Though lab-grown meat is a relatively new space, recombinant proteins have been around for decades, mostly for medical purposes. Insulin was the first recombinant protein product: In 1978, a scientist took the gene for human insulin and plugged it into E. coli bacteria to produce it.

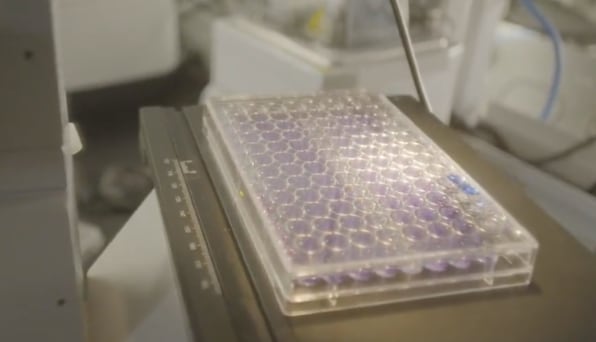

Future Fields starts with a basic strain of Drosophila, or fruit fly. By micro-injecting the desired DNA into the fly eggs, they genetically engineer a strain of fruit fly that will be capable of producing proteins at scale. The team then extracts the proteins from the fly larvae and purifies them.

Future Fields sells the proteins to cell-based meat companies, as well as businesses in other fields, including drugmakers. Today, there are numerous medical uses of these proteins, including in vaccines, stem cell therapies, and wound and burn healing. They are also used in the production of items such as faux leather, dishwasher tablets, and cosmetic creams.

The innovative model was cooked up by Anderson-Baron and his wife, Jalene, cofounder and COO. When they founded the company in 2018, they had originally envisioned being a cultured chicken and fish company, until, when in line for doughnuts at Tim Hortons, they thought of using fruit flies as hosts for growing recombinant proteins. They then pivoted to developing the new biotechnology that they call EntoEngine.

It’s distinct from the current standard method of production of recombinant proteins, which is similar to beer fermentation. “You’ve got to grow these things in big, massive, energy-sucking stainless steel tanks,” Anderson-Baron says. These tanks, called bioreactors, hold cell cultures as they proliferate in carefully controlled conditions.

It’s an expensive technology, and hard to scale. Globally, bioreactor capacity is currently 61 million liters, which will have to grow by 163 times in the next eight years to meet demand.

For cultured meat companies, these proteins represent 50% to 85% of the total production cost, so they need that price to drop in order to make their products affordable for consumers. The days of the $330,000 lab-grown burger are gone, but a pound of cell-based meat could still set a buyer back $40 in the grocery store.

According to Future Fields, its process is 30 times faster than bioreactors, and easily scalable because of the fast maturation period of the fruit fly. To get more biomass, they simply need the flies to reproduce—and they do so comfortably at room temperature, and quickly, with 11-day cycles from egg-laying to adulthood (versus 100 days for other insect candidates like mealworms).

The process also has sustainability benefits. Bioreactors take a lot of energy to sustain optimal conditions and produce biohazardous waste. But the raw materials for fly-rearing are natural: the insects themselves and the foods that make them grow, including sugar and yeast. (Future Fields’s process is also free of fetus bovine serum, a controversial and pricey growth medium used by some protein producers.)

And much of the biomass waste can be upcycled: the flies’ lipids as feedstocks, and their manure, known as “frass,” as a potent fertilizer.

Future Fields has already commercialized its product and shipped it to 60 different cell-based meat companies. Last week, the company announced an extension of its seed funding, with a new infusion of $11.2 million, including checks from Toyota Ventures, AgFunder, and Climate Collective.

Anderson-Baron says the capital will allow for the construction of a new 10,000-square-foot plant in Edmonton, where the flies will be reared in vertically stacked plastic containers. This will enable Future Fields to scale swiftly and reach its objective of making tens of kilograms (up to 200 pounds) of proteins in the next three to four years, which Anderson-Baron admits doesn’t sound like much, “but for recombinant proteins, it really is a lot.”

He adds, “It’s a really, really efficient way of doing it, because insects are just so bloody good at making more of themselves.”