- | 9:00 am

AI is surging in the Middle East. But humans will need to shape the tech

Scholars, ethicists, and technologists discuss how humanity can steer AI responsibly.

Few technologies in history have spread this quickly, such as AI. In less than a decade, narrow applications in search engines and predictive text have evolved into generative systems that can produce essays, images, music, and even scientific hypotheses.

What makes AI different is not just the speed of adoption but its scope. It does not merely alter industries; it touches the very process of thought, expression, and judgment. It also reflects the biases, ambitions, and blind spots of its makers.

Most people agree that there needs to be laws governing AI as the pace of development accelerates. Some are more concerned about “AI safety.” And others are worried about “AI ethics.”

At a recent session, part of the AI Ethics conference organized by the Hamad bin Khalifa University, in Qatar, thinkers and leaders’ perspectives differed, but the consensus was clear: AI is not autonomous. It is us, projected at scale. The true question is not what machines will become, but who we are willing to be in relation to them.

Rejecting that AI could be capped, Dr. Munther Dahleh, director of MIT’s Institute for Data, Systems, and Society, said, “Technology will continue to evolve. The question is, how do we harness it in a way that doesn’t harm?”

He described AI as part of a continuum of digital mediation. “Every picture on your smartphone is computationally processed,” he said. “Digital mediation is already in our lives.” In other words, humans have long lived in mediated environments, but the scale and subtlety of AI change the stakes.

When Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press spread in 15th-century Europe, it democratized knowledge but also destabilized authority. Today, AI promises empowerment but threatens to magnify polarization, disinformation, and surveillance.

ACCOUNTABILITY AND DESIGN

If inevitability is one side of the story, accountability is the other. According to Dr. Dafna Feinholz, Director of the Division for Research, Ethics and Inclusion, UNESCO, argued that embedding ethics into AI must happen by design, not as an afterthought. “We need to ask constantly: for what purpose? Who benefits? Who is harmed?”

Dr. Feinholz has been instrumental in crafting UNESCO’s global framework for AI ethics, endorsed by nearly 200 nations, but knows frameworks alone are not enough. Governance, she emphasized, requires vigilance, inclusion, and clarity about human values. And above all, it requires a refusal to anthropomorphize machines. “AI systems do not have agency, feelings, or ethics. Humans do,” she said. The accountability for harm cannot be shifted to algorithms, it remains firmly human.

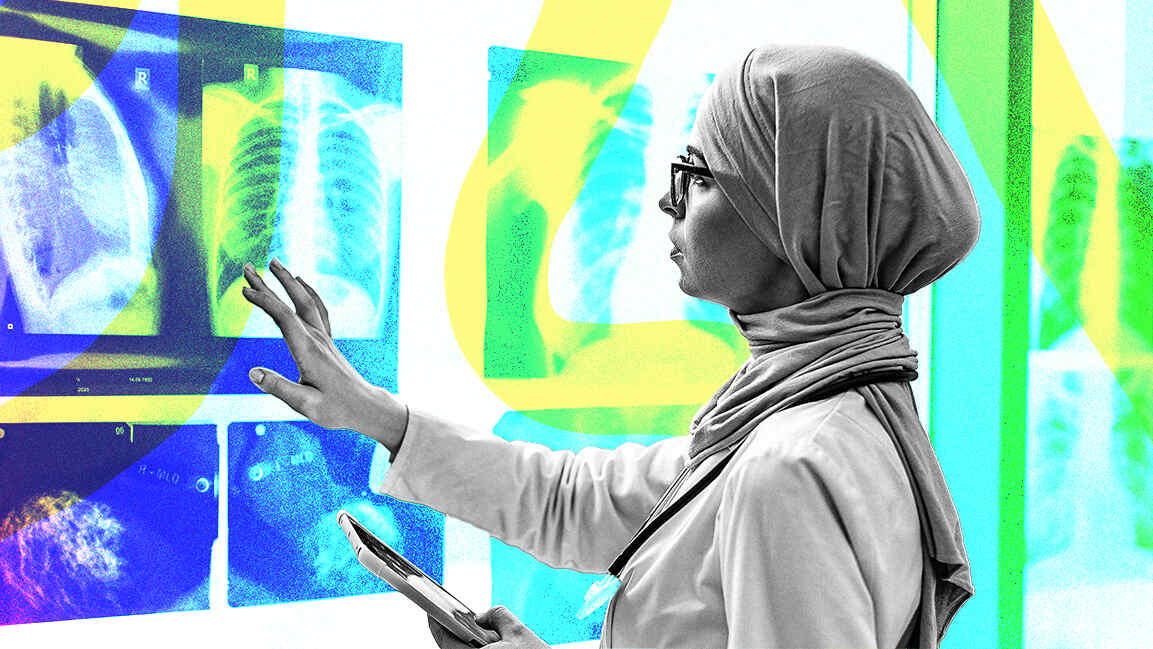

Her caution carries weight at a time when policymakers are struggling to catch up. The European Union’s AI Act, passed in 2024, classifies uses of AI by risk and restricts the most dangerous, from biometric mass surveillance to predictive policing. In the US, the debate is fragmented, with competing pressures from industry, national security, and civil liberties. China, meanwhile, has embraced AI as an engine of state control and economic growth, embedding it in surveillance, censorship, and urban governance. The UAE is simultaneously advancing its ambitious national AI initiative, aiming to become the world’s first AI-native government. Together, these efforts underscore the Gulf’s growing role in shaping the governance, deployment, and moral framework of artificial intelligence, ensuring that technological progress is guided by both regional priorities and global principles.

MORALITY AND MOTIVE

Dr. Mohammed Ghaly, professor of Islam and Biomedical Ethics at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Qatar, drew a distinction between technological capability and moral legitimacy. “Not everything technologically possible is morally acceptable,” he said.

He recalled how Islamic scholars in the 9th century engaged with artificial creation, not to profit, but to explore divine mysteries. Today’s AI, by contrast, is largely shaped by neoliberal capitalism and geopolitical competition. “Big Tech is not operating in a vacuum,” he warned. “Their governing philosophy is profit and authority.”

This framing forces an uncomfortable question: if AI is driven primarily by private incentives and state power, where does that leave society’s capacity to demand accountability? And if the metric is profit, what space remains for ethics?

HUMAN SKILLS AND EROSION

Dr. Mark Coeckelbergh, professor of Philosophy at the University of Vienna, reflected on what might be lost. “There is always de-skilling with new technologies,” he said. Generative AI in particular risks privileging speed over thought, productivity over reflection. The danger, he argued, is not simply replacement but erosion: humans becoming dependent on shortcuts that weaken critical thinking and creativity.

Still, he resisted fatalism. “Humans are always involved in the process. Responsibility remains with us.” The implication is stark. Technology may reshape human capacities, but it cannot erase accountability unless society willingly abdicates it.

Dismissing machine intelligence, Dr. Dahleh said, “ChatGPT or Gemini are just auto-completion on steroids,” Scaled across information systems, these predictive engines could amplify division, curate reality, and entrench bias, he added.

Dr. Feinholz pointed to real-world harm. Industries are beginning to face consequences, from fines to lawsuits to public outrage, but often too late. She cited cases of adolescents who took their own lives after harmful AI-driven interactions. Each tragedy underscores a simple truth: behind every abstraction of “users” are human beings whose vulnerabilities are magnified by opaque, unregulated systems.

The stakes rise even higher in governance. “Machines have no empathy, no bodily vulnerability,” Dr. Coeckelbergh said. Agreeing with him, Dr. Feinholz said while machines can execute commands, only humans can bear moral responsibility.

Across their perspectives, a shared recognition emerged: AI is a mirror, reflecting the incentives, structures, and values of those who design and deploy it. As Dr. Ghaly asked, “We must ask what values govern this technology. Is it money? Power? Or human dignity?”

That question may define the century. Already, AI has become a frontier of geopolitical competition, a battleground of regulation, a test of corporate responsibility, and a challenge to human ethics. However, it is also a test of whether societies can resist outsourcing judgment to machines and whether individuals can reclaim responsibility in an age of scale.

The future of AI depends on how governments regulate, companies prioritize, communities demand transparency, and individuals insist on values that still feel human.