- | 8:00 am

Airbnb is going back to its apartment-sharing roots with Rooms amid tighter regulation

Your NYC Airbnb might not be legal—and the city is cracking down. Airbnb has a solution.

Airbnb, the short-term-rental behemoth, announced today that it’s putting “Rooms”—the concept that basically jump-started the sharing-economy movement back in 2008—front and center on its platform.

This “touches the soul of the company,” said Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky in a press conference ahead of the announcement. Though the company has always offered travelers the ability to book a room in a shared space—the original Airbnb proposition—those lower-budget stays took the backseat over the past decade as the company emphasized its inventory of entire houses and apartments, and even staffed luxury villas.

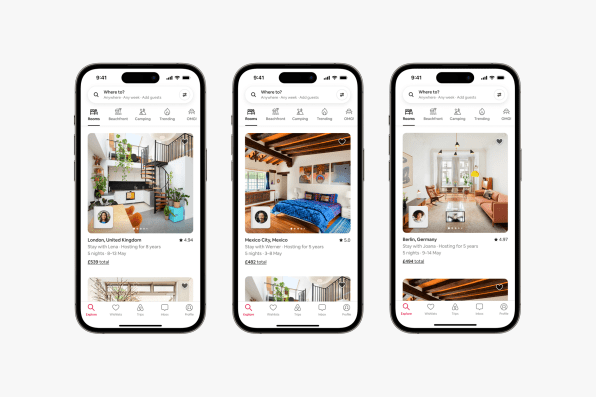

With the relaunched Rooms, Airbnb is highlighting these shared spaces in a tab right on the home screen, allowing travelers to more easily search for them. It’s also eliminating some of the discomfort around staying with a stranger by including a “Host Passport” alongside each listing, which includes biographical info about the host, along with dating app-style prompts about their personality.

This focus on Rooms could help the company earn back goodwill from travelers who have become increasingly vocal about rising prices on Airbnb. (The average daily rate of an Airbnb listing has increased 36% since 2019, according to David Stephenson on the company’s most recent earnings call.) Currently, Airbnb has one million Rooms on its platform, with an average price of $65 a night, said Chesky. Along with Rooms, the company is also introducing new features that make it easier for travelers to see the total price of a stay for any style of accommodation, to avoid sticker shock. They’re part of a larger push by the company to fix some of its core design issues.

Relaunching Rooms is Airbnb’s most overt effort to go back to its roots after shedding a slew of distracting endeavors (guided trips, hotels, and even a rumored airline) as it prepared for its public offering at the end of 2020 while inside the clarifying crucible of the pandemic. “Airbnb Rooms is an all-new take on the original Airbnb,” Chesky said yesterday, emphasizing the peer-to-peer aspect of the product. “Airbnb’s original tagline was ‘Travel like a human.’ And the human part was always more important than the travel part.”

The emphasis on Rooms—and a return to the original vision of the company—comes as regulators in cities across the country reconsider their short-term rental laws in the face of a nationwide affordable housing crisis. According to BuildYourBnb.com, a site that helps wannabe hosts become short-term rental business owners, as of 2021, more than 320 cities and some 100 vacation towns in the U.S. have enacted some regulations around home-sharing. And that list is growing, with ski resorts, desert towns, adventure destinations, and island oases writing ordinances that make renting out a home for less than a month increasingly complex.

New rules in San Diego took effect this month that limit the number of rentals in most parts of the city to 1% of housing stock and require property owners to receive a permit. The Austin City Council drafted a resolution last December to crack down on illegal and non-permitted short-term rentals. Philadelphia is now requiring licenses from hosts, and Colorado’s ski resort towns of Steamboat and Aspen are deepening regulations in an attempt to bring down housing prices.

“Cities can now look at other places that have regulated short-term rentals, and know that they can successfully craft legislation that works,” says Murray Cox, the founder of Inside Airbnb, a website that collects data on Airbnb’s impact on residential communities.. “It’s become a tipping point.”

One of Airbnb’s most formidable regulatory opponents is New York City, which will begin getting tough with illegal rentals this month. Since 2011, the state has required hosts to be present during guest stays. Last year, New York City adopted Local Law 18, which requires all hosts wishing to rent a room for less than 30 days to register with a city database. Short-term rental platforms like Airbnb, Booking.com, VRBO, and others will see steep fines if they list unregistered (aka illegal) rentals, to the tune of $1,500 for each violation. Hosts, meanwhile, can be liable for a civil penalty of up to $5,000, or three times the revenue generated by the short-term rental for each violation. Buildings that don’t want to see Away suitcases to-ing and fro-ing in their elevators can also opt out by registering on NYC’s prohibited building list.

Notably, Rooms—where hosts are present—are legal in New York City, as are rentals that are longer than 30 days. Airbnb also unveiled a new Monthly tab on its homepage today, designed to help travelers more easily find and sort through long-term booking options. Stays longer than a month currently represent 20% of nights booked on the platform, Chesky said.

Cox’s data shows that about 43% of New York City’s 42,931 total Airbnb listings are for individual or shared rooms within an occupied apartment, and may be legal. A big chunk of the balance—that is, apartments or single-family homes renting for fewer than 30 days without an owner present—will potentially disappear after enforcement of the registration law begins, with perhaps a quarter of the entire Airbnb inventory wiped out. Jamie Lane, vice president of research at AirDNA, a short-term rental data and analytics company, doesn’t believe the rules will impact quite so many listings. Of the 25,000 currently available New York City short-term rental listings across Airbnb and VRBO, he says that about 10,000 are shared or private rooms, which are legal, assuming the owner is home. Of the remaining listings, about 10,000 are either serviced apartments and hotel rooms or long-term rentals, which aren’t subject to the regulations. “So maybe 5,000 properties will be affected by the law,” Lane says.

Airbnb is quick to note that New York City isn’t a primary market. It currently represents less than 1% of the company’s total business, according to Chesky, though urban destinations are regaining ground that was lost during the pandemic. (New York City accounted for 2% of Airbnb’s revenue in 2019, according to the company’s S-1 filing ahead of its IPO.) The city’s efforts to curtail short-term rentals, however, cast a bigger symbolic shadow on the company.

Much of the regulatory scrutiny of short-term rentals is focused on their impact on housing prices. A 2019 paper on the effect of Airbnb listings on housing prices and rents in the United States found that, in the median zip code, about 1 in 9 of the potentially available long-term rentals were instead being used as short-term rentals, “effectively taking them off the market,” says Davide Proserpio, an associate professor of marketing at the University of Southern California who coauthored the study. That same report also showed that a 1% increase in Airbnb listings leads to an annual increase of $9 in monthly rent and $1,800 in house prices for the median zip code in their data.

Caroline Peattie, executive director of the nonprofit Fair Housing Advocates of Northern California, says she sees short-term rentals as problematic when “we are talking about someone who has an in-law unit that they could be renting to a person with a disability, or a person of color, or a low-income resident,” she says. She’s particularly concerned about Northern California coastal communities in Solano, Marin, and Sonoma counties, where long-time residents are worried they’ll be priced out as housing stock is reduced. Marin recently extended a moratorium on short-term rentals, while Sonoma just established caps and exclusion zones for them in April.

Policymakers acknowledge that regulating short-term rentals out of existence won’t solve long-standing housing crises, and many believe the benefits of taxing these properties can help cities grow and thrive. That’s why most newer regulations, like those that went into effect in Atlanta last March, limit the number of rental units that hosts can own (to two in the Big Peach, and only to city residents), require them to pay an annual fee (of $150) per listing, and charge a handsome occupancy tax (8% in Atlanta, though that can shoot up to 15% in some municipalities). According to Inside Airbnb’s Cox, cities are increasingly moving toward a model where hosts have to preregister to short-term rent, and platforms are responsible for ensuring listings are registered.

Airbnb has been helping local officials in these efforts. The company launched City Portal in 2020 to offer local governments and tourism organizations access to data on Airbnb listings in their communities and tools that help with short-term rental law compliance. More than 350 partners are now using the portal.

Airbnb is also trying to make navigating this complex regulatory landscape easier for hosts by partnering with major developers like Starwood Capital Group and Greystar Real Estate Partners to register entire buildings as Airbnb-friendly. The service, which launched in November in more than 25 markets, including Phoenix and Houston, is targeted at “renters interested in hosting a spare room, or their entire apartment when they’re out of town,” according to the company. Today, some 250 properties have received the Airbnb-friendly designation.

Whether Rooms will prove an effective tool in increasing Airbnb’s presence in cities that are adopting more draconian short-term rental restrictions remains to be seen. It will most certainly address affordability concerns, and could help foster more community among users, with hosts serving as neighborhood guides and more for guests. “I don’t have many regrets at Airbnb. But I do miss the idea of the community that was fostered in the early days,“ Chesky said. With Rooms, “we’re doing something a little bit different here, around community, around bringing people together.”