- | 8:00 am

Amazon’s health business is coming into focus

Please don’t say the company is trying to fix healthcare. But it’s melding its pharmacy, in-person, and virtual services into something that feels, well, Amazonian.

In November 2021, Neil Lindsay was named to head Amazon’s health business. It wasn’t because of his medical expertise. He didn’t have any. “The reason I’m in this job is because I know how to build things in Amazon,” says Lindsay, who had spent 11 years at the company in marketing roles relating to Prime, devices, and other areas at the time of his appointment.

At Amazon, maybe even more than other tech giants, proven success at understanding the corporate culture and getting stuff done within that framework is critical. The company cherishes its unique principles and willfully idiosyncratic approach to innovation. Healthcare, a $4.5 trillion business just in the U.S., touches everyone and is rife with unsolved problems, making it a unique opportunity. But even for an outfit as instinctively ambitious as Amazon, figuring out how to make a dent in it hasn’t been easy.

When Lindsay got his job as Senior VP for Amazon Health Services, the company’s best-known foray into healthcare was Haven, a joint venture with JPMorgan Chase and Berkshire Hathaway that aimed to provide better health outcomes for their respective employees at lower costs. After launching with great fanfare—and maybe a certain degree of hubris—the partnership ended up disbanding after less than three years, its mission not even remotely accomplished.

Under Lindsay, Amazon Health has been focused on addressing the needs of an even larger group than Amazon employees: Amazon customers. Two-thirds of U.S. adults are Prime subscribers, according to eMarketer, and their medical issues “kind of mirror what’s going on in the country,” says health tech investor, newsletter author, and Fast Company alumnus Christina Farr. “All the data suggests that we’re all getting older and sicker. And so, if you don’t have healthcare as part of what you offer, it’s going to be a giant gap.”

Lindsay’s major contribution over his first three years as Amazon’s health chief has been to focus the business on achievable goals that play to the company’s strengths. “If you think about core Amazon, what we’ve done over decades is find things that can be a little bit easier and then stack them up to make them a lot easier,” he explains. Ultimately, he defines his job as helping “help people who know a lot more about healthcare than I do find a path to executing the mission and achieving the mission, and to really help them align resources.”

For now, that effort has three major components. There’s Amazon Pharmacy, an online seller of prescription medicine that launched in November 2020. One Medical, the chain of storefront primary care offices that Amazon acquired in 2023 for $3.9 billion, adds a physical footprint. And One Medical Pay-per-visit provides inexpensive virtual care covering areas such as acne, contraception, and UTIs.

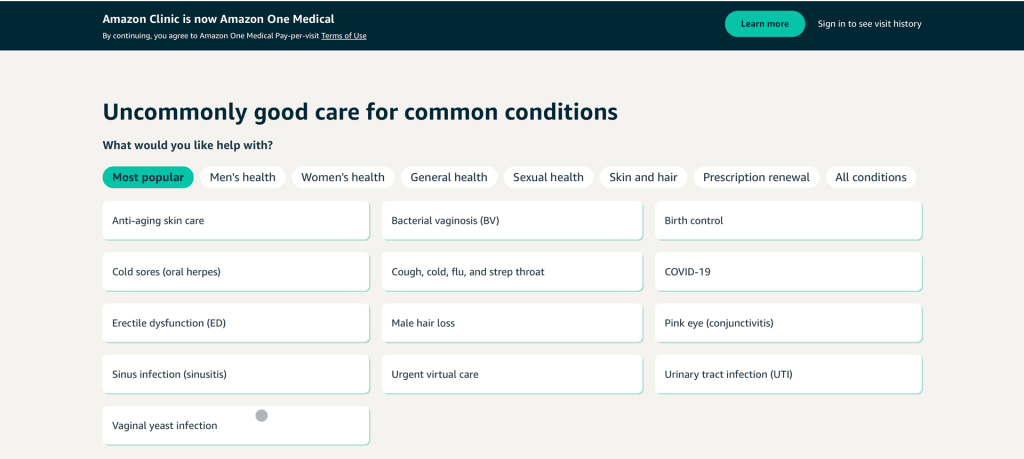

Refining how these businesses relate to each other—and Amazon as a whole—has been a work in progress. After buying One Medical, Amazon left the brand largely distinct for a while. Earlier this year, however, the company began labeling it as “Amazon One Medical.” The virtual care service was initially called Amazon Clinic; in May, it got renamed Amazon One Medical Pay-per-visit—a bit of a mouthful, but a clearer linkage to the membership-based One Medical service. TV and podcast ads now promote One Medical and Amazon Pharmacy with a shared tagline—“healthcare just got less painful”—that ties them back to Amazon’s overarching identity by emphasizing convenience.

The company has also built out an Amazon.com health section that features all three services and is reachable from a link occupying premium real estate right below the Amazon logo on the main Amazon site. “If you think about it, we’ve always said that our mission is to make it easy to find, choose, support, and engage with everything you need to get and stay well,” says Lindsay. “The starting point is to make it make it easier to find, to make sure people are aware that Amazon has these services, too.”

At a company as sprawling as Amazon, there are a lot of places that starting point might lead. In April, in Amazon’s annual shareholders’ letter, CEO Andy Jassy described Amazon’s health offerings as “important building blocks” for the whole company, and said they were beginning to help serve greater goals.

“Because of our growing success,” Jassy wrote, “Amazon customers are now asking us to help them with all kinds of wellness and nutrition opportunities—which can be partially unlocked with some of our existing grocery building blocks, including Whole Foods Market or Amazon Fresh.” That certainly hints at further interminglings to come.

As it edges in that direction, Amazon has not shied away from hard decisions relating to its investment in health. In 2022, for example, it shuttered a hybrid telehealth/in-person service called Amazon Care. Last February, it cut hundreds of jobs at One Medical and Amazon Pharmacy, one of many waves of layoffs that have recently roiled the tech industry. The company says that the cutbacks don’t represent a scaling back of its commitment to the overall business.

One Medical also received some negative press last June, when Caroline O’Donovan of The Washington Post (owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos) reported that a One Medical call center in Tempe, Arizona, had been slow to connect some elderly patients reporting urgent systems with appropriate care. In a response, the company called the report “egregiously misleading and incomplete” and said its data showed 97% satisfaction from callers.

Lindsay is careful not to brag too much about what Amazon Health Services has accomplished so far or overly stoke expectations for what could be. Over the course of two conversations, he reminds me six times that Amazon doesn’t have “a magic wand” that will let it “fix healthcare.” Chipping away at such a complex problem “sort of inspires us, actually,” he says. “If it’s big enough, there’s a need for customer obsession to improve experiences. If it was easy, then it wouldn’t be like this.”

Meds through the mail

Five months after unveiling the Haven project back in 2018, Amazon made another investment in health that was more obviously up its alley by paying $750 million to acquire PillPack. The Boston-based mail-order pharmacy, which used robots to divvy medications into convenient labeled packets, had inspired comparisons to Amazon’s tech-savvy commerce all along (including in this 2014 Fast Company article).

PillPack, which still exists as an Amazon brand, focuses on patients who take multiple meds for chronic conditions. But Lindsay stresses that the idea all along was to use it as a springboard for a larger online pharmacy with a broader customer base—a yen the company first expressed back in 1998 when it invested in a startup called Drugstore.com. “PillPack enabled us to launch Amazon Pharmacy,” he says, citing the licenses and distribution capabilities the startup had assembled.

Even now, almost a quarter of the way into the 21st century, the internet has done only so much to transform how people get prescriptions. Last year, a McKinsey study reported that just 13% of respondents said an online or mail-order pharmacy was their principal source of meds. However, Amazon Pharmacy VP John Love—an 18-year veteran of multiple Amazon businesses whose father once worked at a pharmacy—notes that the typical brick-and-mortar experience hasn’t changed much in decades and leaves plenty of room for improvement.

“You walk in, there’s a counter and somebody behind it in a coat,” he says. “You find out the price of the meds at the point of purchase . . . You’ve got to drive, you’ve got to deal with their hours, you’ve got to wait, potentially. You talk about a private health issue—you know, the pharmacy closest to my house is right next to the hot dogs and the cheese.”

In case you were not aware, Amazon sells hot dogs and cheese, too. But Amazon Pharmacy is walled off from the rest of the e-commerce megasite and, at this point, is fairly basic in presentation. Amazon’s typical sprawling plenitude is not the idea; familiar elements such as customer reviews and recommendations of related products wouldn’t make sense and are therefore absent. A “Pharmacy Assistant” chatbot, currently in beta, can field customer service issues and answer questions such as “Do you dispense Wegovy?” but, in my experience, begs off responding to anything that sounds like a request for medical advice. Actual human pharmacists are available for consultation 24/7 via chat or phone call.

Overall, Amazon Pharmacy’s value proposition—easy ordering, low prices, and speedy delivery—certainly fits into Amazon.com. And beneath the surface, there’s some sophisticated technology in place, such as machine-learning algorithms that estimate insurance prices when Amazon can’t instantly retrieve them.

Even for a company with as much experience at wrangling millions of products and their prices as Amazon, prescription medicine is a unique challenge. Pharmaceutical companies often offer coupons, particularly for generics, but awareness is low: Amazon Pharmacy Chief Medical Officer Vin Gupta cites a 2018 Massachusetts survey that found that even when a coupon was available, respondents took advantage of it only 15% of the time.

Historically, patients “won’t know to download the form off a website,” Gupta says. “It’s a very convoluted, paper-heavy process, both for the provider and the patient. And so, John [Love]’s background at Amazon, Neil [Lindsay]’s background at Amazon, the retail roots of the company, making it as easy as possible for things like paperwork and automating what we can, it’s a big deal for some of these random medications.”

By facilitating access to such discounts, Amazon Pharmacy offers Prime members discounted pricing—80% or more off for generic medicines, and 40% or more for branded ones—that beat insurance pricing in some instances and offer more flexible refill windows. And in January 2023, the company did something truly Amazonian by announcing a new Prime benefit called RxPass. For a flat $5 a month, including shipping, members are covered for over 50 generics, including much-prescribed ones such as amoxicillin, lisinopril, finasteride, and cephalexin. They span 80 different conditions impacting 150 million Americans.

RxPass isn’t completely unprecedented: Arielle Trzcinski, a healthcare analyst at Forrester, points out that Walmart started selling some generic drugs for $4 in 2006. Due to the licensing complexities of operating an online pharmacy, RxPass also remains unavailable in the two most populous states, California and Texas, as well as Washington State. But it’s gone from being available in 42 states to 47 since launch.

To implement the service, Amazon had to pick drugs it could afford to sell for a flat $5 a month. And even then, RxPass “is not a huge margin maker,” says Love. Still, the economics are helped by the kind of efficiencies the company understands. And since the service is a Prime benefit, it caters to the kinds of loyal customers whose overall patronage redounds to Amazon’s overall bottom line.

RxPass’s flat $5 rate is about more than cutting prices. “It also brings transparency and consistency to the cost of medications,” says Trzcinski, who notes that in a country with as many health problems as the U.S.—40% of the population has hypertension—anything that increases the chances of people taking care of their conditions is an accomplishment. Simply making it clear how much you’re going to pay for their medications matters enough to Amazon Health Services that it recently added “Clarity of Cost” as a pillar of its mission, which already included three other Cs: “Choice,” “Convenience,” and “Continuity of Care.”

By contrast, in the conventional, physical pharmacy experience, the price of a prescription remains a mystery until you pick it up. “That’s when you find out what it costs, unless you happen to already know, because you’ve had it before,” says Lindsay. “Even then it can change. And if you go to a different pharmacy, you might get a different price, because of the way the system works. While there’s a lot of things out of our control in that situation, we’re going to take responsibility for giving as much clarity as we possibly can.”

Primary Care meets Prime

When Trent Green signed on as One Medical’s chief operations officer in July 2022, he didn’t know that the company was days away from announcing that it had agreed to be acquired by Amazon. Upon hearing the news, “I just got even more excited.” he says. “There’s a lot of almost direct overlap between what we define as our DNA and the Amazon leadership principles.”

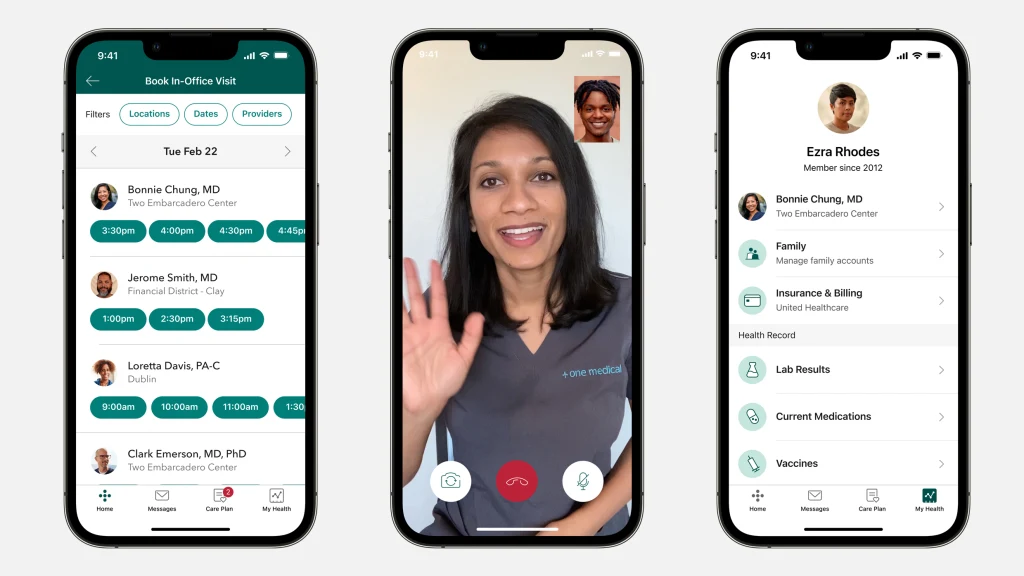

In September 2023, Green was named to succeed Amir Dan Rubin as One Medical’s CEO, giving him full responsibility for the company and its relationship with the rest of Amazon. Currently available as a subscription service in 24 areas around the U.S., Amazon One Medical operates more than 225 storefront medical offices located with convenience in mind. (For example, there’s one on the ground floor of the San Francisco office tower where I work.) Their services cover everything from physicals to the flu to chronic conditions to mental health; an app lets subscribers schedule appointments, engage in telehealth sessions, and look up lab results and other records.

Founded in 2007, One Medical sprang from the same yen to bring new thinking to old problems that motivated Amazon to enter the health business. Surveys show that the vast majority of Americans are dissatisfied with their healthcare experiences. “They can’t get in,” former CEO Rubin told me. “They don’t know how to navigate. They can’t get a question answered.”

One Medical aims to lessen such frustrations with offerings such as same- or next-day appointments, unhurried doctor sessions, and drop-in lab services. Behind the scenes, rather than relying on prepackaged software provided by major electronic health records providers, the company created its own platform, embracing technologies such as machine learning, which it uses to route patient emails to the correct team members.

Amazon’s numerous experiments in brick-and-mortar experiences have had more than their share of dead ends. But as the company was defining the scope of its health offerings, it’s easy to see why it coveted One Medical’s physical footprint. A 2022 Bain & Company study forecast that by 2030, 30% of primary care would be provided via various untraditional venues, such as retail stores and concierge health startups. The opportunity has also attracted some of Amazon’s biggest rivals, though executing on it is no cakewalk: In April, Walmart announced it was shutting down its 51 health clinics and telehealth service.

For all the services Amazon knew it could deliver virtually, recalls Amazon Health Services Chief Medical Officer Sunita Mishra, it also knew that “there’s a handful of things that you need to do [face to face] to treat certain conditions. Depending on the demographic, anywhere between 15% to 35% needs to be done in person. But also, some people just want to be seen in the doctor’s office. In healthcare, we call that having somebody lay hands on you to really build that therapeutic relationship.” Since acquiring One Medical, Amazon has opened 25 new locations; it’s getting ready to enter two new markets, New Jersey and Milwaukee.

On a tour of one of One Medical’s 38 offices in the San Francisco Bay Area, Chief Medical Officer Andrew Diamond told me the company aims for a calm efficiency you might not associate with a visit to the doctor. “You don’t hear a lot of phones ringing,” he told me. “You don’t see a lot of people waiting for more than a couple minutes, because generally, as soon as you sit down, the doctor’s going to come out and get you and bring you back to your appointment. Everything starts on time and ends on time.”

Making primary care more pleasant isn’t just about pleasantness. Earlier in Green’s career—which began at the Mayo Clinic in the 1990s—”I had seen what happens when you don’t get good primary care—you end up in a level one trauma center or a cardiac center or a neurosciences center,” he says. With 100 million Americans lacking a primary care provider, many issues that could get caught early develop into crises.

Along with keeping individual Americans healthier, Green realized, getting them to see doctors on a more routine basis could help tame the runaway economics of the American healthcare system. “It was glaringly obvious that you could prevent enormous amounts of waste if the primary care doctor actually were truly in a position of primacy,” he says. More than 10,000 companies now offer One Medical as a benefit to their employees; a 2020 survey showed doing so resulted in 45% savings on total medical and prescription costs.

Though One Medical represents an attempt to transcend some of the hassles of healthcare in its traditional form, it isn’t trying to entirely wall itself off from the system as it’s long existed. Last month, it announced a partnership with the 103-year-old nonprofit Cleveland Clinic to open primary care offices in Northeast Ohio starting next year. It already has similar relationships in other regions, including Mass General Brigham in Boston, UHealth in Miami, and UCSF Health in San Francisco.

These affiliations connect One Medical’s primary care with resources it doesn’t provide itself, such as access to specialty care and hospitals—a necessary component of any healthcare offering that’s hard to get right. “My mom struggles with One Medical, because her needs have become a lot more complex as she’s gotten older,” says newsletter author Farr. Integrating primary care offered by companies such as One Medical with that provided by specialists, she adds, “has been a struggle across the board.”

Amazon’s acquisition of One Medical was a bet that it could further grow the company’s subscriber base, which stood at 836,000 members at the end of 2022, its last year as a public company. As part of Amazon, it no longer discloses a figure. But post-acquisition, as Amazon was looking for ways to scale up the business, it had a powerful firehose of potential patients at its disposal: all those Amazon Prime members.

“Pretty quickly,” Green says, “we started to explore what it might look like if [One Medical and Prime] were to get connected in some form or fashion.” In November 2023, Prime members got the ability to subscribe to One Medical for $9 a month or $99 a year, plus $6 or $66 per additional family member up to a maximum of six. Compared to a stand-alone One Medical plan—which is only available on a yearly basis—the savings range from 45% to 64%.

One Medical’s double life as a Prime benefit has become core to the way Amazon markets the service. A promo for the Prime option dominates the top of One Medical’s website, and the One Medical section on Amazon.com is Prime-centric in its explanation of the service and its pricing. It may not quite be a peer of free shipping or Prime Video, but for something that’s been part of Amazon for less than two years—and remains a departure from the stuff that springs to mind when you think about the company—it’s been brought well into the fold.

Healthcare for the (mostly) healthy

Like a lot of people in positions of authority at Amazon, One Medical Pay-per-visit Chief Aaron Martin is a seasoned insider at the company, with almost nine years of experience on his résumé relating to its Kindle and self-publishing businesses. But that was all before the end of 2013, when he left to oversee strategy and innovation at Seattle-based healthcare nonprofit Providence Health & Services. He then spent the next eight years in various roles at that organization, which merged with St. Joseph Health in 2016, as well as serving as a board member for several health tech companies.

And then, as an outsider with a background in healthcare, he boomeranged back to Amazon in early 2022. Lindsay, only a few weeks into his job as Amazon Health’s chief, convinced Martin to return as head of third-party platforms and partnerships (his title is now VP, Amazon Health Partnerships and Marketing). The role includes overseeing One Medical Pay-per-visit, which launched in November 2022 under its original name of Amazon Clinic.

That One Medical Pay-per-visit rolls up into Martin’s portfolio reflects one of the basic differences between it and Amazon’s other health initiatives: The people doing the virtual consultations aren’t Amazon employees. Instead, as with Amazon Marketplace—which presently accounts for more than 60% of merchandise sold on Amazon.com—the Pay-per-visit business is ultimately “about matching buyers and sellers” says Martin. In this case, the sellers are doctors, physician’s assistants, and nurse practitioners; Amazon’s role is connecting customers with providers licensed in their states, hosting the virtual consultations, and handing off any prescriptions to a pharmacy for fulfillment. (That pharmacy can be Amazon Pharmacy, but in the interest of fulfilling one of Amazon Health Services’ four pillars, “Choice,” it can also be any other one you prefer.)

The health matters covered by the service are pretty expansive: 38 conditions and other issues in all, including acid reflux, dandruff, erectile dysfunction, male hair loss, tooth pain, motion sickness, pink eye, allergies, contraception, and smoking cessation. For $49, you can consult with a provider via a video call; for $29, you can do so through a messaging session. Either option includes 14 days of follow-up via messaging. Insurance is “not accepted or needed,” as the site puts it, but the fees are FSA/HSA eligible.

The name Amazon One Medical Pay-per-visit does not indicate that this offering is anything like a near-twin of One Medical in its traditional form (which has its own virtual visit functionality as part of its app). The “Pay-per-visit” part might be more important: In a not-so-subtle way, it communicates that a good chunk of the intended audience consists of people who lack a primary care doctor.

Often these patients “don’t really have a chronic disease burden or something like that, and just need something dealt with very, very quickly,” says Martin. By its nature, the service skews toward young people who are lucky enough not to have to think that much about their health (“When I was 23, I couldn’t even spot my primary care doctor out of a lineup,” he notes).

Unlike the One Medical subscription service, which retains its own app, Pay-per-visit lives inside the main Amazon site and app. That is a meaningful choice—and in its own way, the rough equivalent of brick-and-mortar drugstores adding in-store clinics.

“It’s got to be accessible at Amazon, because people come to Amazon often,” says Lindsay. “Making it easy to engage is about not requiring someone who has a one-off need to have to go get another app to do that.”

Paper cut prevention

Just building out its current trio of offerings seems to be providing Amazon Health Services with more than enough work to keep itself busy. It is, however, allowing itself to paint around the edges a little. In January, it announced a program that connects customers with third-party virtual health services that their insurance may cover, with prediabetes, diabetes, and hypertension care company Omada Health as its first partner. It added Talkspace’s online counseling service in September.

When I asked Lindsay if Amazon Health would take on other big, daunting problems relating to healthcare over time, he didn’t exactly say no. But he steered the conversation towards “paper cuts”—Amazon-ese for a class of frustrations Jeff Bezos has defined as “little tiny customer experience deficiencies” worth solving even when they seem minor rather than monumental. The historic inability to determine medication pricing until after you’ve filled a prescription is one that Amazon Pharmacy has addressed, but an infinite number of others remain available to tackle.

“There’s many, many paper cuts,” Lindsay says. “And we’ll spend a lifetime addressing paper cuts.”

Along the way, will it make money for Amazon? That’s the goal, of course. Lindsay argues that there’s nothing about that motive that’s at odds with the more idealistic way Amazon Health Services usually talks about its goals.

“There’s no mission without margin,” he says, quoting Irene Kraus, a nun who ran a nonprofit hospital chain. “So it is a business. But we also believe strongly that a profit without purpose isn’t that much fun either. Can this be a good business? We believe so. But it’s only going to be a good business if we actually improve health outcomes in the process.”