- | 1:00 pm

GPT-powered deepfakes are a ‘powder keg’

Dozens of startups are using generative AI to make shiny happy virtual people for fun and profit. Large language models like GPT add a complicated new dimension.

In the old days, if you wanted to create convincing dialogue for a deepfake video, you had to actually write the words yourself. These days, it’s easier than ever to let the AI do it all for you.

“You basically now just need to have an idea for content,” says Natalie Monbiot, head of strategy at Hour One, a Tel Aviv-based startup that brings deepfake technology to online learning videos, business presentations, news reports and ads. Last month the company added a new feature incorporating GPT, OpenAI’s text-writing system; now users only need to choose from the dozens of actor-made avatars and voices, and type a prompt to get a lifelike talking head. (Like some of its competitors, Hour One also lets users digitize their own faces and voices.)

It’s one of a number of “virtual people” companies that have added AI-based language tools to their platforms, with the aim of giving their avatars greater reach and new powers of mimicry. (See an example I made below.) Over 150 companies are now building products around generative AI—a catch-all term for systems that use unsupervised learning to conjure up text and multimedia—for content creators and marketers and media companies.

Deepfake technology is increasingly showing up in Hollywood too. AI allows Andy Warhol and Anthony Bordain to speak from beyond the grave, promises to keep Tom Hanks young forever, and lets us watch imitations of Kim Kardashian, Jay Z and Greta Thunberg fight over garden maintenance in an inane British TV comedy.

Startups like Hour One, Synthesia, Uneeq and D-ID see more prosaic applications for the technology: putting infinite numbers of shiny, happy people in personalized online ads, video tutorials and presentations. Virtual people made by Hour One are already hosting videos for healthcare multinationals and learning companies, and anchoring news updates for a crypto website and football reports for a German TV network. The industry envisions an internet that is increasingly tailored to and reflects us, a metaverse where we’ll interact with fake people and make digital twins that can, for instance, attend meetings for us when we don’t feel like going on camera.

Visions like these have sparked a new gold rush in generative AI. Image generation platform Stability AI and AI wordprocesser Jasper, for example, recently raised $101 million and $125 million, respectively. Hour One raised $20 million last year from investors and grew its staff from a dozen to fifty people. Sequoia says the generative AI industry will generate trillions in value.

“This really does feel like a pivotal moment in technology,” says Monbiot.

But concerns are mounting that when combined, these imitative tools can also turbocharge the work of scammers and propagandists, helping empower demagogues, disrupt markets, and erode an already fragile social trust.

“The risk down the road is coming faster of combining deepfakes, virtual avatar and automated speech generation,” says Sam Gregory, program director of Witness, a human rights group with expertise in deepfakes.

A report last month by misinformation watchdog NewsGuard warned of the dangers of GPT on its own, saying it gives peddlers of political misinformation, authoritarian information operations, and health hoaxes the equivalent of “an army of skilled writers spreading false narratives.”

For creators of deepfake video and audio, GPT, short for generative pretrained transformer, could be used to build more realistic versions of well-known political and cultural figures, capable of speaking in ways that better mimic those individuals. It can also be used to more quickly and cheaply build an army of people who don’t exist, fake actors capable of fluently delivering messages in multiple languages.

That makes them useful, says Gregory, for the “firehose” strategy of disinformation preferred by Russia, along with everything from “deceptive commercial personalization to the ‘lolz’ strategies of shitposting at scale.”

Last month, a series of videos that appeared on WhatsApp featured a number of fake people with American accents awkwardly voicing support for a military-backed coup in Burkina Faso. Security firm Graphika said last week that the same virtual people were deployed last year as part of a pro-Chinese influence operation.

Synthesia, the London-based company whose platform was used to make the deepfakes, didn’t identify the users behind them, but said it suspended them for violating its terms of service prohibiting political content. In any case, Graphika noted, the videos had low-quality scripts and somewhat robotic delivery, and ultimately garnered little viewership.

But audio visual AI is “learning” quickly, and GPT-like tools will only amplify the power of videos like these, making it faster and cheaper for liars to build more fluent and convincing deepfakes.

The combination of language models, face recognition, and voice synthesis software will “render control over one’s likeness a relic of the past,” the U.S.-based Eurasia Group warned in its recent annual risk report, released last month. The geopolitical analysts ranked AI-powered disinformation as the third greatest global risk in 2023, just behind threats posed by China and Russia.

“Large language models like GPT-3 and the soon-to-be-released GPT-4 will be able to reliably pass the Turing test—a Rubicon for machines’ ability to imitate human intelligence,” the report said. “This year will be a tipping point for disruptive technology’s role in society.”

Brandi Nonnecke, co-director of the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology, says that for high-quality disinformation, the mixture of large language models like GPT with generative video is a “powder keg.”

“Video and audio deepfake technology is getting better every day,” she says. “Combine this with a convincing script generated by ChatGPT and it’s only a matter of time before deepfakes pass as authentic.”

DEEPERFAKES

The term deepfakes, unlike the names of other recent disruptive technologies (AI, quantum, fusion), has always suggested something vertiginously creepy. And from its creepy origins, when the Reddit user “deepfakes” began posting fake celebrity porn videos in 2017, the technology has rapidly grown up into a life of crime. It’s been used to “undress” untold numbers of women, steal tens of millions, enlist people like Elon Musk and Joe Rogan in cryptocurrency scams, make celebrities say awful things, attack Palestinian-rights activists, and trick European politicians into thinking they were on a video call with the mayor of Kiev. Many have worried the software will be misused to doctor evidence like body camera and surveillance video, and the Department of Homeland Security has warned about its use in not just bullying and blackmail, but also as a means to manipulate stocks and sow political instability.

For years, all the negative stories kept customers and investors away from deepfakes. But after a period of what Monbiot says was marked by media “scaremongering,” the tech has seen a turn toward greater acceptance, “from really trying to convince people, or just getting people’s heads around it.”

Lately, she says Hour One’s own executive team has been delivering weekly reports using their own personalized “virtual twins,” sometimes with the Script Wizard tool. They are also testing ways of tailoring GPT by training it with Slack conversations, for instance. (In December, Google and DeepMind unveiled a clinically-focused LLM called Med-PaLM7 that they said could answer some medical questions almost as well as the average human physician.) As the technology gets faster and cheaper, Hour One also hopes to put avatars into real-time video calls, giving users their own “super communicators,” enhanced “extensions” of themselves.

“We already do that every day,” she says, through social media. “And this is almost just like an animated version of you that can actually do a lot more than a nice photo. It can actually do work on your behalf.”

But, please, Monbiot, says—don’t call them deepfakes.

“We distinguish ourselves from [deepfakes] because we define ‘deepfake’ as non-commissioned,” she says. The company has licensed the likenesses of hundreds of actors, whose AI-morphed heads only appear in videos that meet its contractual agreements and user terms of service: “never illegal, unethical, divisive, religious, political or sexual” content, says the legal fine print. For known personalities, use is restricted to “personally approved use.” The company also places an “AV” watermark on the bottom of its videos, which stands for “Altered Visuals.”

The people themselves look and sound very real—in some cases too real, ever so slightly stuck in the far edge of the uncanny valley. That sense of hyperreality is also intentional, says Monbiot, and another way “to draw the distinction between the real you and your virtual twin.”

But GPT can blur those lines. After signing up for a free account, which includes a few minutes of video, I began by asking Script Wizard, Hour One’s GPT-powered tool, to elaborate on the risks Script Wizard presented. The machine warned of “data breaches, privacy violations and manipulation of content,” and suggested that “to minimize these risks, you should ensure that security measures are in place, such as regular updates on the software and systems used for Script Wizard. Additionally, you should be mindful of who accesses the technology and what is being done with it.”

Alongside its own contractual agreements with its actors and users, Hour One must also comply with OpenAI’s terms of service, which prohibit the use of its technology to promote dishonesty, deceive or manipulate users or attempt to influence politics. To enforce these terms, Monbiot says the company uses “a combination of detection tools and methods to identify any abuse of the system” and “permanently ban users if they break with our terms of use.”

But given how difficult it is for teams of people or machines to detect political misinformation, it likely won’t be possible to always identify misuse. (Synthesia, which was used to produce the pro-Chinese propaganda videos, also prohibits political content.) And it’s even harder to stop misuse once a video has been made.

“We realize that bad actors will seek to game these measures, and this will be an ongoing challenge as AI-generated content matures,” says Monbiot.

HOW TO MAKE A GPT-POWERED DEEPFAKE

Making a deepfake that speaks AI-written text is as easy as generating first-person scripts using ChatGPT and pasting them into any virtual people platform. (On its website Synthesia offers a few tutorials on how to do this.) Alternatively, a deepfake maker could download DeepFace, the open source software popular among the nonconsensual porn community, and roll their own digital avatar, using a voice from a company like ElevenLabs or Resemble AI. (ElevenLabs recently stopped offering free trials after 4Chan users misused the platform, including by getting Emma Watson’s voice to read a part of Mein Kampf; Resemble has itself been experimenting with GPT-3). One coder recently used ChatGPT, Microsoft Azure’s neural text-to-speech system, and other machine learning systems to build a virtual anime-style “wife” to teach him Chinese.

But on self-serve platforms like D-ID or Hour One, the integration of GPT makes the process even simpler, with the option to adjust the tone and without the need to sign up at OpenAI or other platforms. Hour One’s sign up process asks users for their name, email and phone number; D-ID only wants a name and email.

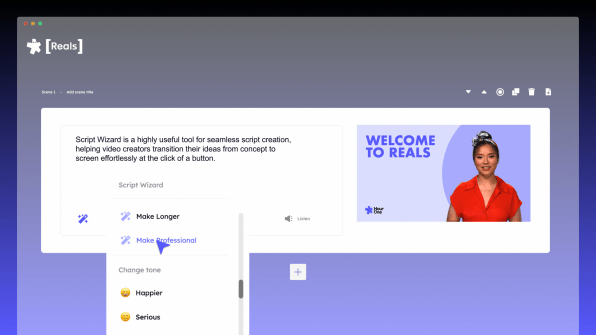

After signing up for a free trial at Hour One, it took another few minutes to make a video. I pasted in the first line from Hour One’s press release, and let Script Wizard write the rest of the text, fashioning a cheerier script than I had initially imagined (even though I chose the “Professional” tone). I then prompted it to describe some of the “risks” of combining GPT with deepfakes, and it offered up a few hazards, including “manipulation of content.” (The system also offered up its own manipulation, when it called GPT-3 “the most powerful AI technology available today.”)

After a couple of tries, I was also able to get the GPT tool to include a few sentences arguing for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—a seeming violation of the terms of service prohibiting political content.

The result, a one and a half minute video (viewable below) hosted by a talking head in a photorealistic studio setting, took a few minutes to export. The only clear marker that the person was synthetic was a small “AV” marker that sat on the bottom of the video, and that, if I wanted, I could easily edit out.

It should be easier to detect synthetic people than synthetic text, because they offer more “tells.” But virtual people, especially those equipped with AI-written sentences, will become increasingly convincing. Researchers are working on AI that combine large language models with embodied perception, enabling sentient avatars, bots that can learn through multiple modalities and interact with the real world.

The latest version of GPT is already capable of passing a kind of Turing test with tech engineers and journalists, convincing them that it has its own, sometimes quite creepy, personalities. (You could see the language models’ expert mimicry skills as a kind of mirror test for us, which we’re apparently failing.) Eric Horvitz, Chief Scientific Officer at Microsoft, which has a large stake in OpenAI, worried in a paper last year about automated interactive deepfakes capable of carrying out real-time conversation. Whether we’ll know we’re talking to a fake or not, he warned, this capability could power persuasive, persistent influence campaigns: “It is not hard to imagine how the explanatory power of custom-tailored synthetic histories could out-compete the explanatory power of the truthful narratives.”

Even as the AI systems keep improving, they can’t escape their own errors and “personality” issues. Large language models like GPT work by mapping the words in billions of pages of text across the web, and then reverse engineering sentences into statistically likely approximations of how humans write. The result is a simulation of thinking that sounds right but can also contain subtle errors. OpenAI warns users that apart from factual mistakes, ChatGPT “may occasionally produce harmful instructions or biased content.”

Over time, as this derivative text itself spreads online, embedded with layers of mistakes made by machines (and humans), it becomes fresh learning material for the next versions of the AI writing model. As the world’s knowledge gets put through the AI wringer, it compresses and expands over and over again, sort of like a blurry jpeg. As the writer Ted Chiang put it in The New Yorker: “The more that text generated by large-language models gets published on the Web, the more the Web becomes a blurrier version of itself.”

For anyone seeking reliable information, AI written text can be dangerous. But if you’re trying to flood the zone with confusion, maybe it’s not so bad. The computer scientist Gary Marcus has noted that for propagandists flooding the zone to sow confusion, “the hallucinations and occasional unreliabilities of large language models are not an obstacle, but a virtue.”

FIGHTING DEEPFAKES

As the AI gold rush thrusts forward, global efforts to make the technology safer are scrambling to catch up. The Chinese government adopted the first sizable set of rules in January, requiring providers of synthetic people to give real-world humans the option of “refuting rumors,” and demanding that altered media contain watermarks and the subject’s consent. The rules also prohibit the spread of “fake news” deemed disruptive to the economy or national security, and give authorities wide latitude to interpret what that means. (The regulations do not apply to deepfakes made by Chinese citizens outside of the country.)

There is also a growing push to build tools to help detect synthetic people and media. The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity, a group led by Adobe, Microsoft, Intel, the BBC and others, has designed a watermarking standard to verify images. But without widespread adoption, the protocol will likely only be used by those trying to prove their integrity.

Those efforts will only echo the growth of a multibillion dollar industry dedicated to making lifelike fake people, and making them totally normal, even cool.

That shift, to a wide acceptability of virtual people, will make it even more imperative to signal what’s fake, says Gregory of Witness.

“The more accustomed we are to synthetic humans, the more likely we are to accept a synthetic human as being part-and-parcel for example of a news broadcast,” he says. “It’s why initiatives around responsible synthetic media need to place emphasis on telegraphing the role of AI in places where you should categorically expect that manipulations do not happen or always be signaled (e.g. news broadcasts).”

For now, the void of standards and moderation may leave the job of policing these videos up to the algorithms of platforms like YouTube and Twitter, which have struggled to detect disinformation and toxic speech in regular, non AI-generated videos. And then it’s up to us, and our skills of discernment and human intelligence, though it’s not clear how long we can trust those.

Monbiot, for her part, says that ahead of anticipated efforts to regulate the technology, the industry is still searching for the best ways to indicate what’s fake.

“Creating that distinction where it’s important, I think, is something that will be critical going forward,” she says. “Especially if it’s becoming easier and easier just to create an avatar or virtual person just based on a little bit of data, I think having permission based systems are critical.

“Because otherwise we’re just not going to be able to trust what we see.”