- | 8:00 am

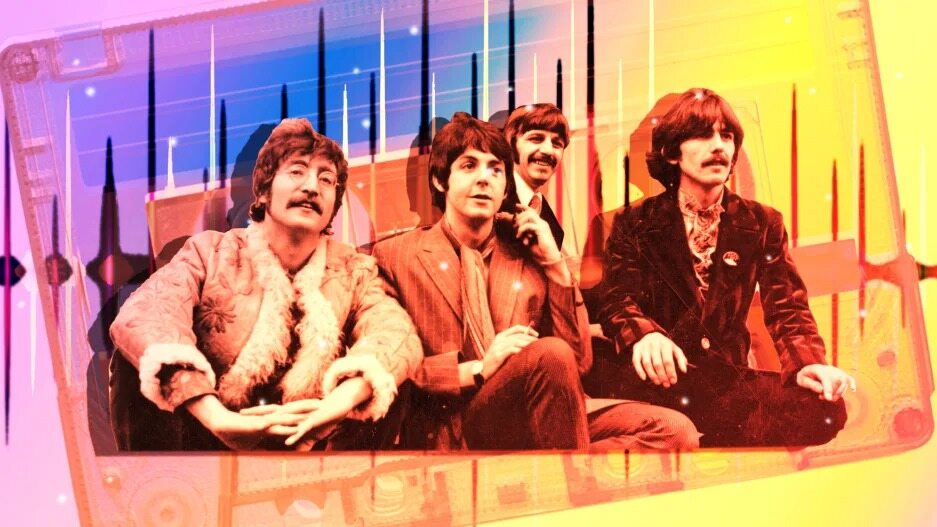

How Beatles producer Giles Martin used AI to reunite the band for ‘Now and Then’

The new Beatles song, which features John Lennon’s vocals, was 50 years in the making—and possible only with AI.

Call it the Beatles’ third law: For every song that’s become an indelible part of the Western pop canon, there’s an equal and opposite “What if?” What if they’d mended the band’s fractured foundation in the ’60s? What if more of them had made it to old age? How many more songs could there have been?

We now have a tantalizing hint at an answer in the form of “Now and Then,” a new single being billed as the final Beatles song. Coproduced by Paul McCartney and Giles Martin, it features elements from all four of the lads from Liverpool—including a John Lennon vocal track that was first recorded as a demo tape in the 1970s. “Now and Then” has been in the works for decades and its existence can be credited, in some part, to the remaining Beatles, Yoko Ono, film producer and director Peter Jackson, and advanced machine learning.

Ahead of working on the 1995 The Beatles Anthology project—which included a television documentary, a three-volume set of double albums, and a book—McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr were given four of Lennon’s demo cassette tapes by his widow, Ono. When the three remaining Beatles came together in the studio, they managed to rework two of those demos into proper songs: “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love.” They also recorded some guitar and drum parts to accompany Lennon’s “Now and Then” demo, but the song proved to be unworkable: The quality of the cassette recording was too low, and the vocal was too mired in Lennon’s piano and the sound of a TV playing in the background.

The demo sat in McCartney’s archives until recently, when Jackson’s work on 2021’s The Beatles: Get Back documentary (which uses archival footage and audio to document the process of making Let It Be) opened the doors to AI-powered audio de-mixing tech. Jackson and his team in New Zealand developed the tech for the film, using it to separate and improve voices and instruments from mono recordings made in the 1970s as part of a Let It Be documentary that was released at the same time as the album.

McCartney asked them to apply the tech to Lennon’s “Now and Then” cassette, and they were finally able to properly isolate his vocals from the background noise and piano. Empowered by the technology, McCartney pushed to turn the demo into a full-fledged Beatles song.

“Paul is not one to sit still on things,” says coproducer Martin, whose father, George Martin, was the Beatles’ longtime producer. “And obviously, he wanted to work with John again.”

Besides recording his own bass parts and harmonies, McCartney unearthed guitar parts that Harrison recorded in 1995, enlisted Starr to play drums, and had Martin write parts for strings. He also created a slide guitar solo inspired by Harrison, who featured the slide guitar prominently in his post-Beatles solo career. The result is a surprisingly seamless song for having been cobbled together by elements from different decades.

Martin says that fans shouldn’t be alarmed by the tech used to create the song. The music industry, he asserts, has been working toward something like this for a long time. He says he tried using a much more primitive version of isolation technology to revisit the Beatles catalog some years ago, “but it wasn’t good enough.”

Even as recently as 2016—when Martin used a less advanced source-separation tool to help reduce the sound of fans screaming to remaster the Beatles’ iconic 1966 Shea Stadium show as part of Ron Howard’s tour documentary, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week—the technology was lacking. “It just wasn’t as effective, and you could hear the transience,” Martin says. “But it was fine because I wasn’t dealing with important things like Beatles’ voices.”

The tech for The Beatles Get Back was a game changer. “I was waiting for this to happen,” Martin says. “Peter and the team cracked it, and we worked on improving it together.”

Martin also says that it’s important for people to understand that human creativity is still at the heart of the song. Even if AI was involved, it wasn’t used to create synthetic Lennon vocals. “It’s key for us to make sure that John’s performance is John’s performance, not a machine learning version of it,” he says. “We did manage to improve on the frequency response of the cassette recording . . . but it’s critical that we are true to the spirit of the recording, otherwise it wouldn’t be John.”

And while the effort is being used, in part, to promote the reissues of the anthology albums 1962-1966 and 1967-1970 (colloquially called the Red Album and Blue Album, respectively), Martin is clear that it’s not a cash grab. He says it was a labor of love, primarily from McCartney. “People find this hard to believe, but it’s not like some marketing executive goes, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to do a new Beatles song?’” he says. “It doesn’t work like that. Paul did it on his own and then he got me in to help.”

Indeed, the song sounds exactly like what it is: an opportunity for the remaining Beatles to return to a period when they were making music with their friends, with lyrics from Lennon that seem presciently nostalgic. (The accompanying Jackson-directed music video is a little more maudlin and a lot less subtle, but perhaps he’s earned the indulgence.) It’s a swan song, sure, but for four minutes and eight seconds, the Beatles are back on the forefront of music.

“They used the tools they had in innovative ways—whether it was tape loops or backwards guitars. . . . “My father always used to say they would just ask the question all the time, ‘Why can’t we do this?’” Martin says. The tools may have changed, but the inventive spirit that helped make Revolver and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band remains—and is on display with the new song. “I love the idea of the Beatles breaking new grounds of technology as they did make when my father was working with them,” he says.