- | 8:00 am

How JetZero aims to be the ‘SpaceX of aviation’

The Southern California aviation start-up is rethinking the commercial passenger jetliner to fight climate change with its blended wing body design.

It takes a moment to adjust. After a lifetime of flying in metal tubes, the reimagined cabin of a JetZero blended wing body jetliner is a revelation. Multiple aisles lined with wider seats and assigned overhead storage fans out in an open triangular floor plan. A back corridor for bathrooms keeps queues away from seats, while rear engines enable a quieter space. It’s an antidote to the loud claustrophobic hellscape that is commercial jetliner travel, especially for those of us in steerage.

This concept display is a compelling glimpse into an aviation future that JetZero co-founders—CEO Tom O’Leary and CTO Mark Page—are hoping to steadily advance towards reality over the next decade. If successful, their blended wing body aircraft could be the first major redesign of a commercial passenger jetliner to enter production. Its lighter weight and superior aerodynamics would deliver the same speed and range as existing midbody jetliners on half the fuel, potentially saving airlines billions of dollars and bringing them a step closer to the Holy Grail of zero-carbon flight.

“We call this the SpaceX of aviation,” says Tony Fadell, the founder and CEO of Build Collective, a JetZero investor and strategic advisor. Fadell co-invented the iPhone and later co-founded Nest Labs (since bought by Google). He regards JetZero as disruptive as the space firm with a similar origin story. Just as the former sprang from frustrated rocket engineers stifled by industry convention, JetZero’s engineering brass spent decades in aerospace developing a better plane for a resistant industry. “They left to create [JetZero] because this is what the world needs to be able to hit climate goals. It has to happen now because we have an existential crisis.”

WHAT IS A BLENDED WING BODY, ANYWAY?

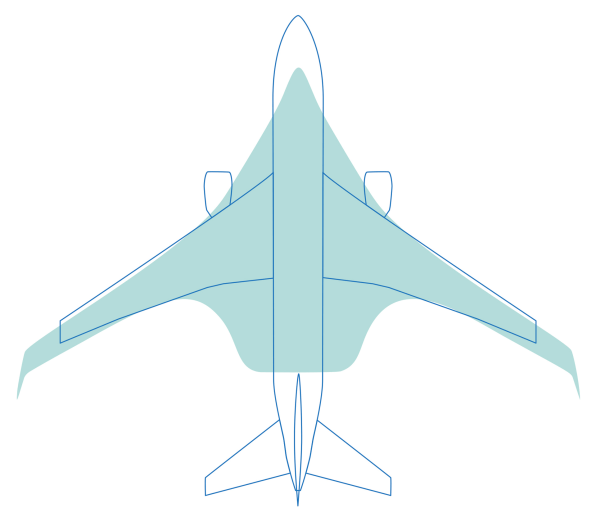

In contrast to the conventional tube and wing design, a blended wing body (BWB) shows no clear dividing line between the wings and fuselage and is often tailless. It’s a more aerodynamic shape that reduces drag and increases lift, enabling the plane to cruise at higher altitudes in thinner air on less fuel. But because the pressurized passenger area is also wing structure, BWBs need to distribute their stretching and bending loads differently. So rather than bolted metal and composites, they’re made almost completely of stitched carbon fiber—a lighter material whose layers and sections are sewn together like fabric with Kevlar “thread,” which withstands stress in more directions than conventional aluminum construction. Finally, the stitched composites are infused with a resin binder and cured into a smooth finish. Additionally, the BWB has fewer moving parts, which makes it cheaper to build and maintain, with fewer points of failure and components to inspect or replace.

The concept is hardly new. The aerospace sector has been developing prototypes for decades—many involving future JetZero engineers. In fact, Page, who was a chief engineer with NASA’s BWB program in the `90s, is considered one of the fathers of BWBs alongside Robert Liebeck, who developed the first prototype for NASA, and Blaine Rawdon, both of whom now serve as JetZero technical advisors.

Compared to other BWB developers, their 2.5-year-old startup is the only one tackling it as a sole business model. “Our folks on the team are the ones who really invented the concept of a blended wing jetliner decades ago and have been honing it ever since, so I think it is entirely fair to say that we’re the leaders in this space,” says O’Leary. “We’re building these aircraft as quickly as we can to accelerate the pace of climate action.”

Global warming is at a tipping point. The 2015 Paris Agreement calls for reducing carbon dioxide emissions to net-zero by 2050 to keep average global temperatures from rising more than 1.5 °C (2.7 °F)—a target some scientists now expect to breach by 2027. Aviation contributes roughly 2.5% of total global emissions which only threatens to grow at an average 4.3% per year over the next 20 years. Analysts anticipate 10,000 more commercial airliners by 2032 and 200,000 daily flights by the mid-2030s, to triple industry emissions by 2050.

The other immediate concern is skyrocketing fuel costs, which account for some 30% of global airline industry expenses and drive up ticket prices. A January 2019 to 2023 comparison by the federal Bureau of Transportation Statistics tracked a 70% increase in per-gallon fuel costs.

“We’ve exhausted the ways we can make tube-and-wing more efficient,” says Nina Jonsson, an Icelandair board member who is advising JetZero. A former fleet manager for Air France-KLM and US Air, she apprises the team of airline needs. “The possible 50% fuel burn savings; I mean, my God, I’ve spent three decades working at the airlines just to get a one percent fuel burn savings and they’re offering 50? There’s this `aha’ moment of, `Oh my goodness, this is a solution!’”

SO, WHY DIDN’T THIS CATCH ON EARLIER?

Although the two major jetliner manufacturers, Boeing and Airbus, have explored their own BWB versions, change moves slowly in a sector that sells product 15 to 20 years in advance and shies away from the risks and costs of production overhauls. “Boeing and Airbus can still make money selling what they have on the lot,” says Page. “They don’t have to make a technology change.”

There was even less incentive during the economic boom times and nascent climate change warnings of the 1980s and `90s. “Three or four decades ago, there was no pressure whatsoever to change the tube and wing design,” says Jonsson. “Prices were low, planes were selling nicely. There was no green focus.”

Over time, consumer and industry attitudes changed with more extreme weather, rising air travel prices, and public intrigue with whimsical crafts like electric air taxis. This landscape was apparent in 2016 when O’Leary, then COO of electric aerospace firm Beta Technologies, hired Page, who’d cofounded military drone designer DZYNE Technologies, to consult on a project. As they worked together, Page mentioned his BWB design and asked for advice on bringing it to market. O’Leary was intrigued by the concept.

After a few years of planning, they launched JetZero in September 2020, attracting a lean and enthusiastic staff that’s supplemented by outside specialist engineering firms and advisors. Significantly, women hold several senior engineering and operations leadership positions that per JetZero is above the industry average.

“When I found out about what Tom and Mark were up to, it was the most exciting thing happening in aviation; the idea of doing something disruptive,” says Eve Ford, a former Boeing aerospace engineer who is now JetZero’s head of operations. “These people are giants in the aerospace industry. If you worked at a big company with hundreds of thousands of employees, to get the opportunity to work one-on-one with [them] would never happen.”

That sense of mission coupled with the gravitas of its partners will be imperative to weathering anticipated push-back from its competitors. “Boeing and Airbus are going to work really hard to make sure it doesn’t happen,” JetZero advisor Barry Eccleston, the former Airbus Americas CEO, told Aviation Week last month. “We’re getting a bunch of partners that are going to give us real credibility. So, when the first question you get in the marketplace is, ‘How are you going to do all that?’—we have a plan, and we have the strength of partners to do it.”

PATHWAY TO MARKET

Their business strategy involves two major steps to faster market entrée. The first is targeting the underserved mid-market gap between narrow- and wide-body planes. These are jetliners seating 200 to 250 people, which airlines are forced to fly longer because no replacement models exist. Despite its size, JetZero’s mid-body aircraft will weigh no more than today’s narrow-bodies seating only 150 to 200 passengers. Aloft, it will match conventional jetliner speeds of more than 500 mph but fly more than 5000 feet higher to 45,000 feet. The lighter material, combined with better aerodynamics and reduced wind resistance from flying higher, is how it saves fuel.

The second is slotting into existing airport infrastructure: using off-the-shelf engines, as well as established cockpit controls, airport gates, and propellants, like kerosene and sustainable aviation fuel (pricier bio and synthetic fuels with lower carbon footprints). “As we continue to develop, we can integrate future types of propulsion systems using hydrogen as a zero-carbon-emissions fuel,” says O’Leary. The BWB’s larger cargo area would accommodate hydrogen, which emits only water as “exhaust” but takes up four times the volume for the same energy.

For now, JetZero’s concept is still in the testing stages at its Long Beach headquarters, near Los Angeles. The U.S. Air Force, NASA, and a handful of private investors have supplied the undisclosed initial funding to develop the design and gather data with subscale remote-controlled models. Successful tests with “Foamy,” a plastic foam aircraft with a seven-foot wingspan, have paved the way for summer trials with a 23-foot version, dubbed Pathfinder. The company, in partnership with aerospace pioneer Northrop Grumman, is currently competing for Air Force funding to build a full-size 200-foot prototype it hopes to demo in 2027. The goal is an early-2030s entry to service as commercial jetliners for airlines and refueling tankers and cargo freighters for the Air Force.

But billions are ultimately needed to bring it to market. So, last month, the startup unveiled its vision to dozens of potential investors, Air Force personnel, and airline reps at its Conceptual Design Summit Potential at its Long Beach Airport hangar. There, guests toured a life-size makeshift cabin layout, tried out its flight simulator, and checked out its test and concept models. Fast Company joined for an exclusive first look.

“You’re gonna be the very first person to `board’ this plane,” teases O’Leary. He guides me through an ersatz jetway into a sprawling cabin that spreads out like theater seating. “You’re meant to be looking into the future. We’re visualizing a commercial jetliner in a blended wing body airframe.”

TECH-DRIVEN DESIGN

We enter midway into a spacious triangular cabin, on a walkway extending through its width. Rows of seats fan out on either side, just 14 rows deep for faster boarding, with only one or two wider seats lining these aisles. There are no middle seats.

JetZero worked with aviation cabin designers Factorydesign and Applied Mobility Partners to concurrently develop interior and exterior layouts. It’s a suggestion of what’s possible, as airlines will ultimately determine their own configurations.

“[The shape] gives the airlines more optionality,” says O’Leary. “The airline industry has become a race to the bottom with respect to comfort. But if you can reduce the fuel burn, you can use the savings to make a more comfortable cabin and create larger seats without as much economic penalty.”

At this stage, the display is primarily embellished particle board, more about layout than look, so no photos are allowed. But O’Leary and the design leads describe potential for LED mood-lighting, moveable seat walls for privacy, skylight windows, and digital displays of outside views for window-less seats. Each seat has a designated storage large enough for a standing roller carry-on and coat. A longer aisle in the back would contain bathrooms and their queues, to keep them from spilling into seating rows.

The layout also benefits flight staff. A central stand-alone food galley creates a more private space for attendants while dividing the cabin into three or four seating bays that include an angled wall of window-facing first-class seats. Pilots get more spacious quarters at the tip of the triangle complete with locked double doors, its own galley, and a bathroom—self-contained for added safety.

HOW DOES IT FEEL TO FLY?

The BWB shape enables a faster climb, but a gentler take-off, cruise, and landing. It’s also significantly quieter. Engines are mounted on the rear upper surface. Because air flows over the top of the plane at supersonic speeds, the soundwaves of the engine roar don’t travel fast enough to come forward into the cabin. Nor do they reflect downward off the underside of the plane. On the ground, the plane would sound like it was four times as far.

“The ability to go above the weather makes things a lot smoother for passengers,” says Bethany Davis, a multi-craft pilot serving as JetZero’s head of programs. “And when you look out the window, it’s a dark blue sky.”

As exciting and novel as such a flight might be for future passengers, it likely pales to the anticipation that comes with a plausible roadmap to the finish line after so many decades of research and at such a crucial time.

“I’ve devoted more than 30 years of my life to refining the blended wing body,” says Page. “Now we’re entering an era that demands emissions reduction on a major scale. When we see the first BWB airliner takeoff, this whole team will feel it’s really made a difference.”