- | 8:00 am

Inside the addictive design behind the hit ‘Monopoly Go’ mobile game

Mobile game maker Scopely has taken in $3 billion from ‘Monopoly Go.’ Players, it seems, can’t stop rolling.

Walter Driver would like your attention, please. As the cofounder and co-CEO of Scopely, the mobile games company behind such free-to-play hits as Monopoly Go!, Scrabble Go, Marvel Strike Force, and Star Trek Fleet Command, he knows your time is precious. That’s why his games never demand much more than a minute or two to play—unless, of course, you choose to keep going. Better to lure users in with little notifications that inspire a minute of play here, a few seconds there, slipping into the never-ending rhythm of smartphone pickups a user makes throughout the day.

Those minutes add up. In the past year, Scopely’s 500 million users have played its games for 5 billion hours. That equates to approximately 570,000 years’ worth of human attention.

Scopely doesn’t simply captivate users’ time, though. It captures their money, in similarly small increments. Power-ups, skins, boosts, spins, dice rolls, and other virtual items—priced from $1.99 to $60 or more—add up, too: Users spend an average of $90 every month, and the company is nearing $10 billion in lifetime revenue since its launch in 2011. At a time when the rest of the mobile games market is stagnant—global revenue declined 2% overall, to $107.3 billion, in 2023—the Los Angeles–based company is rocketing ahead. In 2024, it became the top U.S. game maker in both the iOS and Google Play app stores by revenue, and the fourth-largest mobile games company in the world.

“They are masters of engagement and retention,” says Brian Ward, CEO of Savvy Games Group, the Saudi Arabia–backed holding company that spent $4.9 billion to acquire Scopely in July 2023. Ward, a veteran video game executive, has a mandate to invest heavily in the industry to position the nation for the future, as part of its Vision 2030 initiative to diversify away from oil and gas.

Savvy plans to build and acquire gaming assets in mobile, console, PC, and beyond, putting some of them under Scopely’s management. Ward believes that Scopely’s free-to-play, fragmented model of micro time and micro transactions represents the future of all gaming and entertainment. Scopely’s games “attract players who play seven days a week—for years at a time,” Ward says. “That’s the special sauce of Scopely. That’s what they do better than anybody else.”

A fifth of Scopely’s lifetime revenue stems from just one game: Monopoly Go. Released in April 2023, the game hit $1 billion in revenue after seven months—and another $1 billion three months later. It’s now at $3 billion in revenue, according to Hasbro’s latest earnings. The game has reached 150 million downloads and has 10 million daily active users.

What makes Monopoly Go go? Most of the credit goes to Scopely’s meticulous approach to designing games as irresistible, bite-size gems of entertainment. But these bright and playful mobile games are also masterful at using things like frequent notifications and intermittent rewards to hook users’ attention and wallets.

This work is underpinned by Scopely’s tech and analytics platform, which identifies patterns across billions of hours of gameplay, allowing the company to refine and perfect its approach with each new game. At a time when companies of every stripe, from sports betting to social media, are drawing on data science, behavioral economics, and gamification tactics to nudge and manipulate humans, Scopely has perfected the form. It’s a titan of digital-era capitalism, dressed as a cartoon robber baron.

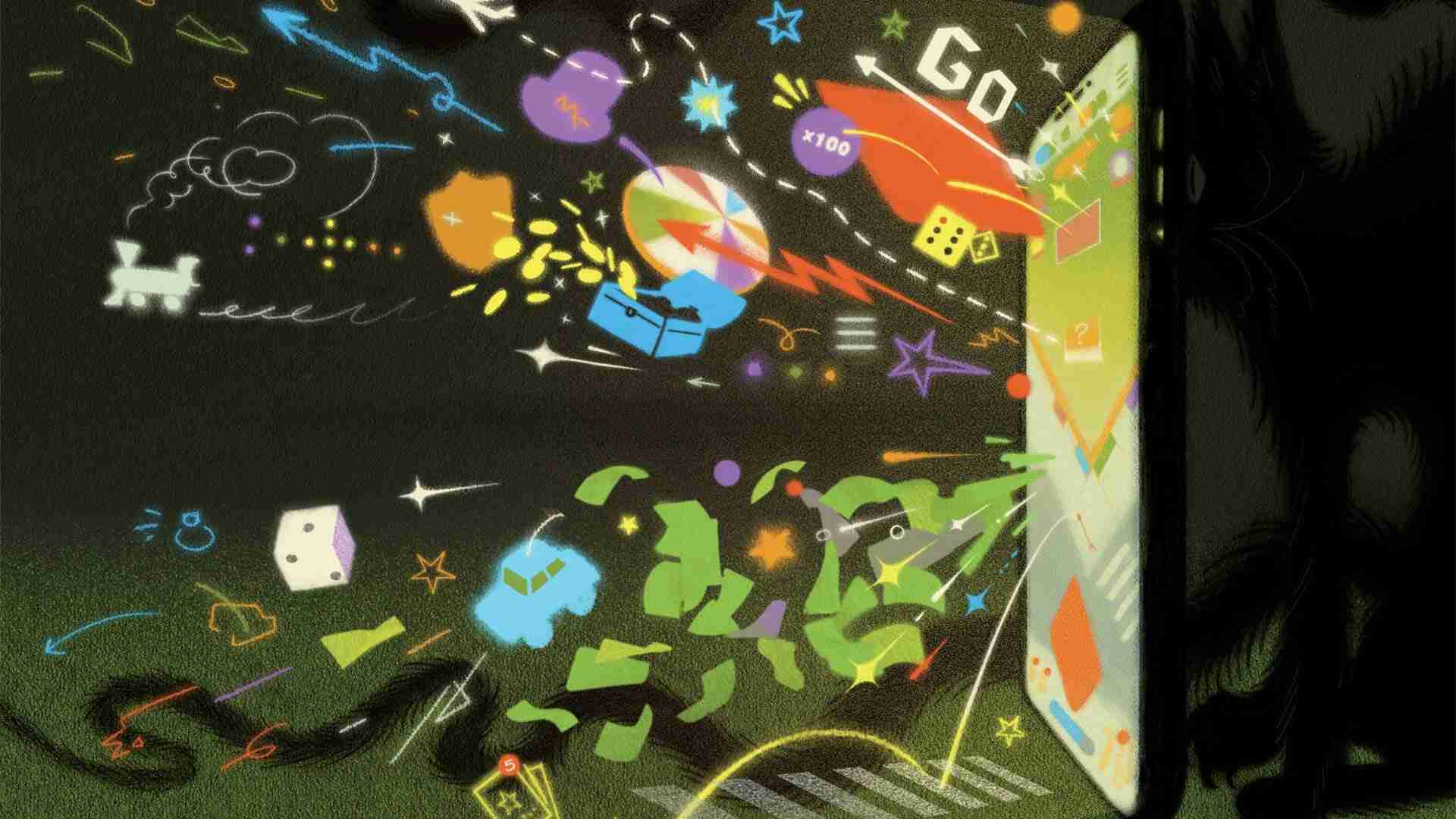

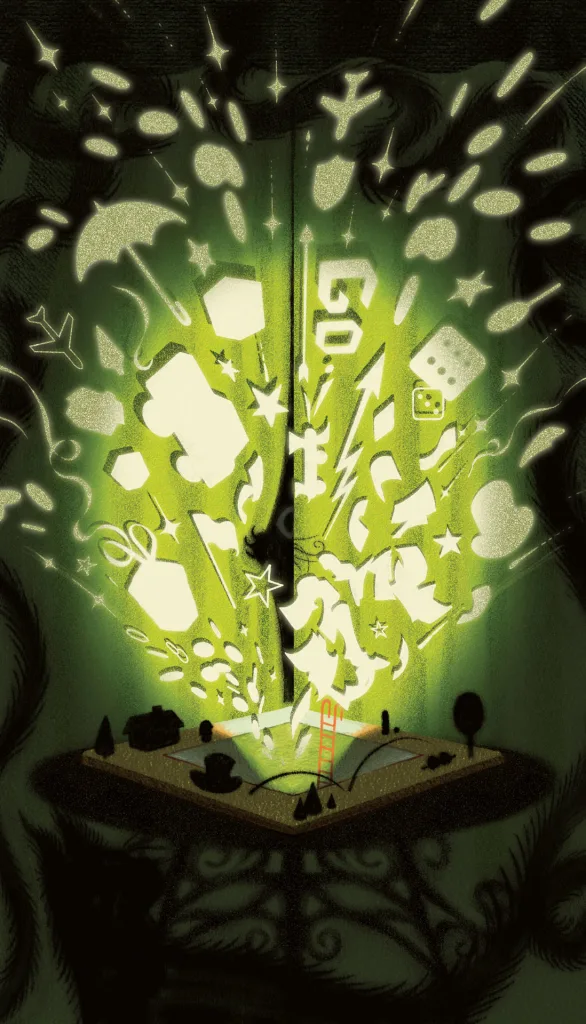

It’s the most beloved moment for anyone who played the board game in childhood: getting your turn to roll. Press the large red go button on the bottom of the Monopoly Go screen, just above where a smartphone user’s thumb normally rests, and two dice clatter across the board, the phone’s haptics rumbling in sync. Your game piece marches around the colorful board, which resembles a plaza in a toylike city; its inevitable stop is welcomed with a burst of candy-colored cash and cheers from the plaza’s miniature citizens. Unlike a real Monopoly board, where you have to fear landing on other players’ properties and paying rent, this one is filled almost exclusively with moneymaking opportunities, unless your piece lands on a tile like Jail, Income Tax, or Luxury Tax, which come with a minimal fee.

In Monopoly Go, it’s always your turn to roll. Press go again: The dice clatter, the piece moves, the cash rains down, the phone vibrates along harmoniously. Hold the go button and it turns green, allowing the dice to start rolling automatically. The dice tumble; the cash flutters. Every so often, bells ring and fireworks explode.

“I Can’t Stop Rolling” is what Scopely general manager Massimo Maietti, who led Monopoly Go’s design team, internally named the first phase of game development. Dice rolling should be so satisfying that users will never get bored. “We felt if [rolling the dice] wasn’t fun, we have no game,” he explains. With only a few inches of smartphone-screen real estate to work with, the game makers fixated on minute aspects of the design, refining colors, tweaking the timing of the rolls. When a player rolls a 2, the dice take their time to land, teetering between one number and another, to compensate for the fact that the game piece will only move two tiles. If a player rolls a 12, the game piece starts moving early, before the numbers even settle—adjustments that slow and speed the game piece’s march to an even, satisfying tempo.

This attention to game mechanisms that keep people playing has been baked into Scopely since its earliest days. The company grew out of Driver’s interest in creating social games for Facebook, which he began pursuing after his dreams of becoming a Hollywood actor and screenwriter sputtered. When social games like FarmVille took Facebook by storm in 2009, Driver launched Stardom, a game that allowed people to achieve celebrity by organizing virtual parties and events on Facebook.

While Stardom was modestly successful, Driver saw a bigger opportunity: He could build a company that was more like a movie studio, providing game makers with marketing and distribution muscle. He recruited Ankur Bulsara, a Cornell grad with a computer science degree; Eric Futoran, a lawyer and strategy consultant; and Eytan Elbaz, an L.A.-based investor and one of the cofounders of Applied Semantics, the company behind Google’s AdSense product. In 2011, the four of them launched Scopely. The company, as they envisioned it, would build and acquire games. But its real focus would be to harness consumer attention through a combination of data analysis and clever mischief.

“We had this fun viral app called Friend Buzz,” says Bulsara, “back when Facebook notifications were a little bit of a wild west. We would post to the user 20 questions about their friends, like ‘Is Bobby smart?’ Or ‘Is Lindsay a liar?’ Then we’d send a notification to Bobby, like, ‘Hey, your friend answered a question about you: Do you want to figure out what the answer is?’ And to get the answer, Bobby would have to answer 20 questions.” (Bobby et al. would also have to click through a number of ads, too, generating revenue for Scopely.)

As casual gaming migrated from social networks to mobile phones, Bulsara and Driver applied ideas traditionally associated with the freemium software-as-a-service business to their own free-to-play games—concepts like customer acquisition costs and lifetime value of an average customer. The idea: If you can just get a customer on board and create a compelling enough game mechanism, a reliable percentage of them will never leave.

Behind the scenes, Bulsara began developing an internal tool that would later become a centerpiece of Scopely’s strategy: Playgami. Among other things, it collects and analyzes a vast array of gameplay data emitted by the company’s games—when users logged in, how long they played, what they clicked on, and (crucially for Scopely’s business) when they forked over money. Under Bulsara and Playgami CTO Hugo Pibernat, who joined in 2016, the platform allows Scopely to identify patterns in the gameplay, cluster and segment different user types, and run A/B tests to see which kinds of promotions and features perform best.

As Zynga’s Scrabble-like Words With Friends took off, Scopely acquired, for a small six-figure sum, Dice With Buddies, a knockoff of Hasbro-owned Yahtzee, and began optimizing it. Eventually Hasbro took a can’t beat ’em, join ’em approach and let Scopely turn Yahtzee into a mobile game in 2015. (Scopely also launched its first Hollywood-based game that year, The Walking Dead: Road to Survival.) Yahtzee With Buddies continues to make money nearly a decade later: In a single 30-day stretch this past spring, it made $5.2 million and was downloaded more than 180,000 times, according to mobile research and tracking firm Data.ai.

But Monopoly, as board games go, is the crown jewel: The game is known by an estimated 98% of the global population, according to Hasbro. After watching Yahtzee transform into a mobile moneymaker, Hasbro handed Scrabble over to Scopely (Scrabble Go launched in 2020) and then Monopoly. It was a winning move: Monopoly Go “is the biggest licensing success that we’ve had as a company,” says Chris Cocks, CEO of Hasbro, which also owns such iconic brands as G.I. Joe and Transformers. And while competitor Mattel may have seen a splashier return from the blockbuster success of the Barbie movie, 2023’s most celebrated use of toy IP, that was a onetime thing. Hasbro, by contrast, has a quieter but much steadier pipeline with Monopoly Go. (Hasbro gets a guaranteed minimum and then a percentage of net revenue for the lifetime of the game.) It’s been so successful that Hasbro has now converted the mobile game back into a physical game. “This is a partnership and a financial annuity,” Cocks says, “that will pay dividends for years to come.”

If the first part of Monopoly Go’s development focused on the crucial moment for players—the dice roll—phase two of the game’s design focused on the crucial element for Scopely: all that colorful cash that players accumulate as their piece rounds the board. Maietti called this phase “Just One More Billion.”

For the virtual money to have value, players have to be able to do something with it. So the developers took inspiration from the board game. There, players erect houses and hotels. In Monopoly Go, you create entire worlds, spending your virtual dollars on little monuments and buildings, upgrading each until a larger scene is fully realized, a cutesy tableau of, say, New York City, with Mr. Monopoly’s face on the Statue of Liberty. Once finished, you level up to a new scene—London—where things cost a little more to build. And repeat. The price of everything keeps rising, and somehow it always feels as if just as you’re about to level up, you run out of money.

That’s when the game offers to sell you more dice rolls, or the virtual cash you’ll need for your renovations. Of course, even if you don’t buy more rolls, they’ll eventually replenish. But if you set your phone down and wait for the dice rolls to refill, there’s a sinister catch: Other players may get a chance to smash up your buildings and steal your money.

Monopoly Go requires almost no skill to play. It’s driven instead by luck—and Maietti and team’s elegant harnessing of a primitive lizard brain urge: Play and get rewarded. Stop playing, and others could take your precious. It’s a matter of greed, dedication, and fear, writ small and put on repeat.

There are other ways that the game gets players to spend real money. It runs timed side contests and mini games that reward landing on certain tiles (paying out in limited-run game pieces and emojis), incentivizing players to buy more dice rolls. When a friend smashes one of their buildings, players receive a push notification urging revenge by smashing a building in return, which requires yet more dice. Meanwhile, the game promotes constant sales on bundles of dice rolls, Monopoly money, and other virtual items, like stickers, which can be exchanged for dice rolls and virtual cash.

Players make these purchases because they love Scopely games, Maietti suggests. This is the beauty of the free-to-play model. “When we talk about revenue to the team, when we [want to] say, ‘We make this many million dollars,’ ” says Maietti, “we talk about it in ‘units of love.’ Not dollars or euros.”

Those units of love, of course, brought in $350 million in April 2024 alone, according to Scopely. Driver acknowledges that users are incentivized to keep spending, but says, “They decide it’s worth it to invest in that experience and then do it again and again. If they’re not happy with the choices they’ve made, they’ll ultimately stop.”

But what if the reason that consumers can’t stop rolling has less to do with their total “love units” and more to do with compulsion, conditioned over time by the game’s rewards mechanics? What does Driver say to critics who call his games addictive? When I ask him this in his office in Los Angeles, with his co-CEO, Javier Ferreira, seated at his side, Driver gives me a hard stare. He pauses for 10 seconds before answering.

“We don’t spend a lot of time talking to people who have that perspective, to be honest,” he says. Ferreira chimes in. “What we see on the data side of things is ongoing engagement, but not compulsive engagement.” The company says that players spend an average of 45 minutes a day on its games.

User feedback tells a more complicated story, for mobile games generally and Monopoly Go specifically. Among people who bought something in a mobile game last year, 57% say they want to cut back on their mobile game spending, according to Data.ai’s State of Mobile Gaming 2024 report. Of that group, more than one-fifth want to stop spending on mobile games altogether.

TikTok and Reddit, meanwhile, are teeming with seemingly regretful Monopoly Go gamers. “I’ve spent $30 and I feel guilty just for that,” wrote a Reddit user named Affectionate_Cow6715. “But it’s all for what? Just to end up earning more dice, running out again and wanting to get more dice. Seems like it’s just never ending (I have a gambling addiction).” Another, named Full-Promotion-8195, wrote, “Upvote if you think Scopely has rigged this game.” (Maietti says it’s entirely random: “If you flip tails four times, the fifth time, you still have a 50% chance of tails. But if you have 12 million players, somebody will flip tails 20 times in a row, and they will post on social media.”) The Better Business Bureau, which gives the company a B–, has received hundreds of complaints about Scopely in the last three years. Most of the recent complaints are centered on Monopoly Go, and many are from users frustrated by the game’s seemingly excessive reliance on in-app purchases for more dice rolls.

Game makers have wide freedom to design games as they like, especially in the U.S. Regulators have called out social media companies, increasingly TikTok, for their addictive UX design. And there’s a growing chorus of people demanding more oversight of betting apps like DraftKings and FanDuel for fostering gambling addiction with their versions of “Can’t Stop Rolling” incentives. But mobile games have thus far not been in the hot seat in the U.S., even as research into the behavior of free-to-play game users has revealed troubling similarities to gambling. (In 2021, China issued national screen-time limits for gamers under age 18, with one Chinese state media outlet likening video games to “spiritual opium.”)

In a 2022 essay for The New York Times, William Siu, cofounder of the mobile game developer Storm8, acknowledged the inherent problems with the industry. “We experimented with every feature of our games to see which versions allowed us to extract the most time and money from our players,“ he wrote. “For us, game addiction was by design: It meant success for our business.” The headline of his article: “I Make Video Games. I Won’t Let My Daughters Play Them.”

Apple and Google have instituted more stringent controls around how app makers can track and market to users in recent years. But Mark Terbeek, a partner at venture capital firm Greycroft and a Scopely board member, says he doesn’t worry about them cracking down in any meaningful way: Scopely and other video game makers simply make them too much money. “We’re confident they wouldn’t cut that off,” he says. “The amount of revenue that [mobile gaming] drives for Apple and Google is kazillions of dollars.”

Scopely, meanwhile, has a lot of dice left to roll. With cash flowing in from Reading Railroad to Riyadh, the company is preparing to apply its model far and wide. It’s deploying its Savvy war chest to market Monopoly Go to new customers, and plans to acquire and develop games that it hopes will appeal to the remaining 60% of Americans who haven’t played a Scopely game in the past year.

That includes children: In 2022, Scopely acquired Stumble Guys, a battle royale–style mobile game that’s particularly popular with Gen Z (and Gen Alpha) users. It’s now porting Stumble Guys and other games to the PlayStation and Xbox consoles. Meanwhile, because Monopoly Go is easy to play with friends and family, it’s been making inroads with younger users. Driver recounts his 13-year-old niece’s thrill at telling him, a few months ago, “Every single kid in my grade is playing Monopoly Go! People don’t believe that you’re my uncle!”

And Driver is talking to that other monolith of mainstream American culture: McDonald’s. Could we see a revival of the decades-old Monopoly game promotion as a mobile game? It would be “One More Billion” meets “billions and billions served.” And why not? Scopely’s games are like french fries: easy, tasty, fine in moderation—and, as experts look on with concern, a global force, changing everyday people’s everyday habits forever.