- | 8:00 am

Kids aren’t reading for pleasure—and more than tech is to blame

Doomscrolling. Poor literacy instruction. Overscheduling. These are some of the reasons cited for a generational decline in students reading for fun.

A quarter-century ago, David Saylor shepherded the epic Harry Potter fantasy series onto U.S. bookshelves. As creative director of children’s publisher Scholastic, he helped design and execute the American editions of the first three novels in the late 1990s.

But when the manuscript for J.K. Rowling’s fourth book landed on his desk, Saylor sat up straight: It was huge. Bigger, more complex, and narratively intricate than virtually any storybook ever aimed at children.

“I had to really think,” he said in a recent interview. “‘How are we going to typeset this book? How are we going to print a million copies? How are we going to get enough paper?’”

Bound and shipped, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire clocked in at a formidable 734 pages—2.5 pounds. It was, of course, another in a series of massive hits that collectively spent a decade atop The New York Times Bestseller List, ensnaring both children and adults, including most of Saylor’s friends.

He jokes that until the advent of Potter, “mostly no one cared that I worked in children’s books.” As excitement for the series grew, friends would ask him when the newest installment was due . . . and what happens next?

“Suddenly my job became important,” he said.

But the book and its six co-volumes now serve another purpose: They’re an eloquent proof point in an ongoing conversation in the publishing world: Are kids still reading books?

By the time Potter arrived, Saylor had lived through waves of predictions about the next extinction-level event to doom his industry. First it was TV, then video games. Before that it was radio and comic books, once derisively called “the ten-cent plague.”

“I’m only slightly jaded by these reports,” said Saylor, 65, “only because people are always predicting that kids are going to stop reading, and that the end of publishing is near.”

This time, it feels different.

Even as children’s publishing explodes with new talent and excitement from fans online, new distractions and diversions are precipitously driving down the share of young people who read for fun. It’s a long-simmering problem that even the optimist Saylor acknowledges his industry must confront.

‘The reading class’

Over the course of two generations, from 1984 to 2023, the proportion of 13-year-olds who said they “never or hardly ever” read for fun on their own time has nearly quadrupled, from just 8% to 31%.

During that time, the percentage of middle-schoolers who read for fun “almost every day” has fallen by double digits, according to surveys conducted for the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the test widely known as “the nation’s report card”: In 1984, 35% of middle school kids read for fun almost every day. By 2023, it was just 14%.

The phenomenon is part of a larger shift away from reading, research suggests: A new study from the University of Florida and University College London found that daily reading for pleasure has dropped more than 40% among adults over the last two decades, “a sustained, steady decline” of about 3% per year.

Findings like these have sparked fears that, after more than a century of steadily expanding literacy, reading is devolving into an act relegated to a small group of elites, a “reading class” that enjoys books while the rest of us see them as, in the words of scholar Wendy Griswold, “an increasingly arcane hobby.”

It’s a strange and thorny problem that in some sense seems contradictory: If you followed around a young person for a day, you’d likely see that she is reading constantly, but often in tiny fragments. In addition to school assignments, she’s taking in a ton of atomized content: alerts, text messages, memes and social media posts. All those bits add up for sure—one study found that the typical American reads the equivalent of a slim novel every day—but it isn’t the same as sitting down to read a book.

For young people, that’s having downstream effects, with NAEP reading scores slumping even before the pandemic and college professors increasingly reporting that students are uncomfortable tackling long reading assignments, let alone complete books.

Adam Kotsko, an assistant professor who teaches in the Great Books School, a discussion-based classics program at North Central College in Naperville, Ill., recently reported that his students are intimidated by any reading longer than 10 pages. They seemingly emerge from readings of as little as 20 pages, he said, with “no real understanding.”

That has put pressure on professors to design courses with fewer readings: “I got to a point where I was cutting to the bone so much that there wasn’t even enough to discuss in some class sessions,” he said in an interview. “It seems like the habits of sustained reading are not being taught in the first place, in some cases, and they’re just being replaced with nothing.”

While COVID lockdowns took a toll on reading, the problem predates the pandemic. Many observers point to several possible culprits, including schools’ fraught approaches to reading instruction and two decades of test-driven K-12 school pedagogies, which often de-emphasize fiction in favor of short non-fiction passages.

This has all taken place amid the dawn of smartphones—the iPhone turned 18 in June—and the rapid, unregulated rise of social media. So Kotsko and his colleagues are careful not to place the blame on students’ shoulders, but on a schooling and media ecosystem they can’t control.

“We are not complaining about our students,” he wrote recently. “We are complaining about what has been taken from them.”

‘Continuous partial attention’

Gabriel Baez, 15, said phones are “a big distraction” at his South Florida charter school. As soon as teachers give students even a moment of downtime, the phones come out. Several teachers have begun requiring students to stash them in special pouches during class. “No distractions—that’s the only thing that I think helped a lot of us.”

A sophomore, Baez said he’s excited to read the science fiction thriller Ready Player One—a novel about, of all things, video games. He loved the 2018 Steven Spielberg movie, but said most days he’s overscheduled and barely able to find a minute to open a book.

He’s in class from 7 a.m. to 2 p.m., then does homework until 5 p.m. Dinner is at 6 p.m., then he studies a bit more. From 7 to 8 p.m. it’s soccer training, then bed so he can wake up early and do it all again. “I really don’t have time unless I decide to substitute something.”

For many young people, school is what gets in the way of books.

Julia Goggin, 15, grew up reading books and loving them. She consumed the first few Harry Potter books unassisted in second grade and finished the series by fourth grade. She read a lot in middle school.

In high school? Not so much.

Like Baez, she’s heavily scheduled, running cross country in the fall and track and field in the winter. She’s in her school’s theater group, which means after-school rehearsals. Then homework. All of it leaves little time for reading anything aside from school assignments.

“If a school is too overbearing about forcing kids to read a lot, it makes them not want to read for fun because it’s not fun anymore,” she said. “Because school isn’t fun.”

A junior at a private high school in Wilmington, N.C., Goggin enjoys reading, but said her two younger brothers, eighth- and ninth-graders, don’t. “They never got into reading the same way I did when they were little. Since then, I guess, they’ve just played video games instead. That’s, like, all they do all day.”

Over the years, she has noticed a change in herself: As a kid, she read for relaxation. “But now all I want to do is scroll on TikTok, which is really bad,” she said with a laugh. “Now I have to be more conscious: Instead of going on my phone, I have to make the decision to read, which is different than before. When I was younger, it was just a default.”

To be sure, young people in the U.S. are reading words—lots of words. Perhaps more than ever.

In her most recent book, the literacy scholar Maryanne Wolf noted that research from as far back as 2009 found that the average American reads what amounts to 34 gigabytes of information, or about 100,500 words, daily—from newspapers, magazines, books, games, messages and social media posts. For a bit of perspective, To Kill a Mockingbird, the Harper Lee classic, clocks in at about 100,000 words.

While all that grazing certainly adds up, Wolf said, it’s “rarely continuous, sustained, or concentrated.” Rather, those 34 gigabytes represent “one spasmodic burst of activity after another.”

She said the fact that young people are reading all those words should comfort no one. “It means nothing.” The inability—or the unwillingness—to go deeper is what’s more important. “I think we have, really, a demise of deep reading, which for me is synonymous with critical thinking and empathy and the beauty of the reading act.”

While the 20th century saw literacy rates in the U.S. climb steadily, technological developments such as movies, radio, TV and the Internet shifted modern culture away from reading and writing and toward visual and oral communication. One unintended result: at least two generations of young people who see books and reading as optional.

In the meantime, 65% of 8-to-12-year-olds now have an iPhone or other smartphone, according to a 2024 survey by the market research group YPulse—and 92% of 8-to-12-year-olds are on social media, where they’re inundated with memes and short-form videos.

Carl Hendrick, a Dublin-born professor at Academica University of Applied Sciences in Amsterdam and co-author of the 2024 book How Learning Happens, accuses this generation’s parents of all but abdicating their responsibilities.

He likens smartphones’ cognitive disruptions to the health effects of cigarettes, recalling that he grew up in Ireland at a time when smoking was ubiquitous. “You could smoke on buses—you could smoke on airplanes. You could smoke anywhere. We look back on that now with horror. And I think the same thing will be true of phones. We’ll go, ‘How did we allow 11-year-olds to go onto social media?’”

Hendrick, who has emerged internationally as a leading advocate for improving classroom instruction via better understanding of learning science, said digital distractions are taking a toll, hijacking kids’ ability to engage their working memory on difficult texts and problems. That kind of laser-like focus, he said, is rapidly disappearing from our lives due to the “weaponized distraction” of social media. “It’s at an extraordinary level of sophistication to try and grab your attention,” he said.

In a recent Substack newsletter, he laid down the gauntlet: “Solitude, slowness and sustained attention are no longer default states but acts of resistance. And as those conditions erode, so too does the possibility of the moral work that deep reading once quietly performed.”

While social media sites are the latest offenders, the phenomenon is hardly new. In 1998, the sociologist and computer researcher Linda Stone coined the term “continuous partial attention” to capture the ways in which the first digital television networks allowed users to “connect and be connected” 24/7. She described a kind of early FOMO, or “fear of missing out.” But it also generated an artificial sense of “constant crisis,” a dopamine-generated high alert that’s hard to extinguish.

By contrast, Hendrick said, giving oneself over to reading deeply, whether it’s literature, philosophy or any complex text, offers something more: a rehearsal for real life, and for the patience we need to deal with one another. “It is a rehearsal in understanding before judging, listening before reacting,” he wrote recently. “This is not merely a virtue. It is a survival skill for a pluralistic, tolerant society.”

Ironically, one of the big drivers of the discredited “whole language” movement was to foster a love of books and reading. But what educators missed at the time was that not teaching all kids to read proficiently at a young age meant reading became “more and more laborious” as they got older, since they couldn’t handle more complex texts, said Holly Lane, director of the University of Florida Literacy Institute.

“Nobody likes doing something that they’re not good at,” she said. “They may love the idea of reading, but they don’t like the act of reading.”

That, to many observers, is the original sin of the reading problem: the nation’s uneven commitment to teaching reading in ways we now know are more effective, such as explicit phonics instruction, which systematically teaches students the relationships between letters and sounds. Other, less effective methods, such as “whole language” instruction, emphasize immersion in texts rather than attention to isolated skills.

Like many educators who are pushing schools to embrace scientific approaches to literacy, Lane is hopeful about improvements in states like Mississippi and Louisiana. But she worries that progress at the elementary school level will be wasted if educators can’t help students at the secondary level develop the stamina to read longer, more difficult texts. Without that, she said, they won’t develop into readers. “When they leave high school, even if they can read, they don’t.”

Others worry that the rush to teach phonics without attention to solid background knowledge will continue to yield disappointing results. Phonics instruction is “trendy to care about right now,” said Boston University’s Elena Forzani, but it’s being enacted “in pretty superficial ways” that ignore student motivation. “We’re teaching kids to read in a content and motivational vacuum,” said Forzani, who directs the university’s Literacy Education and Reading Education programs.

In order to be able to read deeply, she said, students need many opportunities to enjoy, analyze, discuss and write about a text and the issues or problems it presents. But when she visits classrooms, she sees students reading short, disconnected “popcorn passages” with new topics every day, sometimes multiple times a day.

While more and more kids are getting the explicit phonics instruction they need at an early age, the vast majority are learning to read “in a very isolated fashion—the focus is on the skills. And kids don’t care about that. They’re humans, like the rest of us. You only want to learn a new skill if it’s going to do something for you.”

‘Very good readers—and voracious readers’

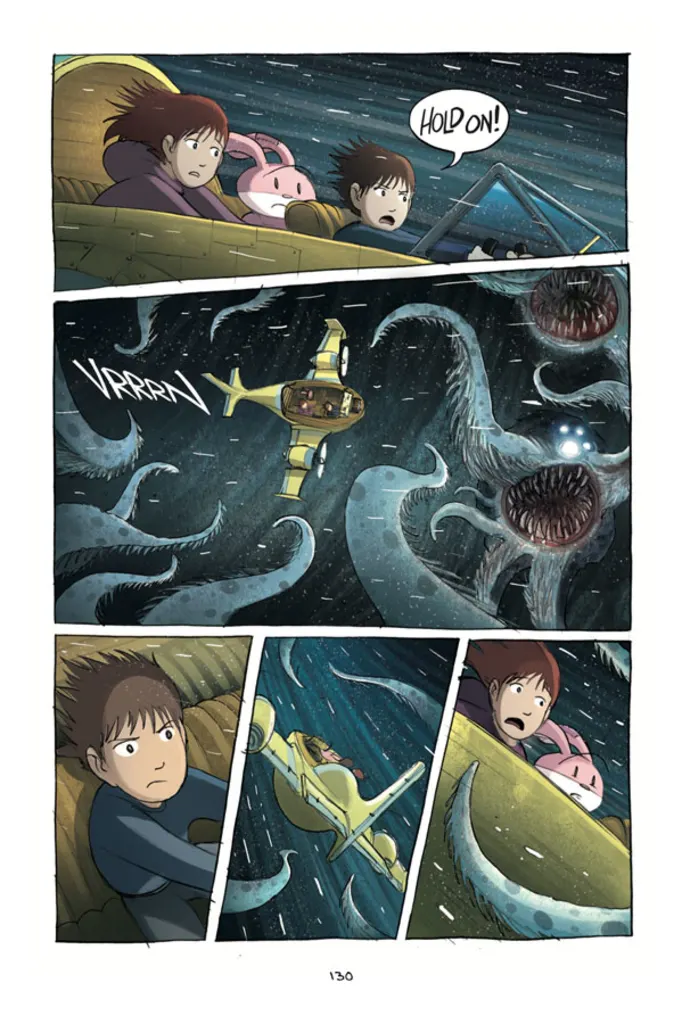

When he visits schools to sign books, the Japanese-American writer and illustrator Kazu Kibuishi sees this in action. His popular nine-volume Amulet series of graphic adventure novels about siblings who must find their kidnapped mother, finds a rapt audience of dedicated fans.

“I don’t really buy that kids are not reading anymore, because I see the opposite of that all the time,” he said in an interview. “I find kids to be very good readers—and voracious readers.”

But state-of-the-art digital entertainment has conditioned them to want more from their media. “Their minds are encoded to get information as fast as possible,” he said. “They have to turn that off when they go to school.”

Kibuishi’s publisher, Scholastic, has gone all in on graphic novels—Saylor, the creative director, even established an imprint dedicated to the genre. Teachers and librarians regularly tell him that kids read them voraciously and repeatedly, “until they fall apart.”

Kibuishi said he creates comics that provide “high-quality, dense information” on every page, with fast-moving, high-stakes plotlines, rich illustrations and heightened emotions from his characters. His inspirations are the classic Marvel comics from the 1950s through the 1980s. “Big ideas were baked into small spaces,” he said.

Creators like Stan Lee and Jack Kirby “put a tremendous amount of life experience” into the slim stories, which he compares to little sponge dinosaurs that expand exponentially in water.

A self-described average student, Kabuishi found his calling in storytelling after reading Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea in high school. “I read it pretty much in one sitting,” he said. “And when I was done with the book, I was transformed.”

The words “felt like pictures, and the book was so short,” he said. It was the first time reading didn’t feel like homework. “I felt like I was on a fishing boat. I felt like I had just experienced the rise and fall of this fisherman’s journey with this fish. And it was so poetic.” The little book “felt so much bigger than any other book than I’d been asked to read in class.”

The struggle to find such magic books is real, said Kelsey Clodfelter, a veteran English teacher at a Chicago public high school. She teaches students whose skills are often years behind where they should be by 10th or 11th grade.

“When reading is hard for you, when it is literally difficult for you to decode words at the age of 16 or 17, reading is a very painful experience,” she said. “It’s also really embarrassing.”

Clodfelter, 35, who has a large TikTok following as “Mrs. C,” said Common Core reforms of the past decade essentially replaced book-length readings with short non-fiction texts designed to prepare students for the kind of reading they’ll do “in the real world.” While it didn’t prohibit longer reading assignments, it may have made it harder for many teachers to assign appropriate books.

And COVID, she said, “really did a number on us in terms of the transactional nature of school,” sending students the clear message that grades mattered more than learning, that standards in general were lower—and that nearly any effort was satisfactory.

The upshot, she said, is that she’s working harder all the time to get kids through reading assignments: She often swaps classic texts for contemporary memoirs, such as I’m Glad My Mom Died by actress Jeanette McCurdy. She invites students to read silently in class for 20-minute stretches. She creates book groups, and even sits with them and reads passages aloud.

“Students still won’t read the book,” she said.

‘Nobody can learn this much’

These days, even the most elite students are rebelling against reading.

Daniel Willingham, a longtime University of Virginia professor, said he has noticed lately that his students—“some of the most successful that the system produces”—not only complain about long readings but about “being asked to learn as much as I ask them to learn.”

Like Clodfelter, Willingham believes the pandemic scaled back expectations that have yet to be restored.

Each year since 1985, he has taught an introduction to cognitive psychology course that has changed little in 40 years. Students read about a chapter a week, averaging 30 pages or so. A careful reading, he said, would require about four hours of work.

“This is the first year since the pandemic [that] I’ve been hearing from students, ‘This is an unreasonable expectation. Nobody can learn this much.’”

A leading authority on cognitive science in the classroom, Willingham suggests to his students that they consider different study strategies. Long an advocate for the importance of broad background knowledge in reading instruction, Willingham said he’s “actually cheered and optimistic” that more educators are realizing the importance of a rich curriculum.

But he worries about the time young people spend online—recent research suggests that they now spend most of their waking hours in front of screens, he said.

That may be the biggest irony embedded in this dilemma: The Internet has seemingly decimated young people’s desire to read books, offering them endless distractions and opportunities to do something—anything—else.

But dig a little deeper and you’ll find it is also doing a lot of heavy lifting, making it easier than ever for young people to find great books and connect to likeminded people who want desperately to talk about them.

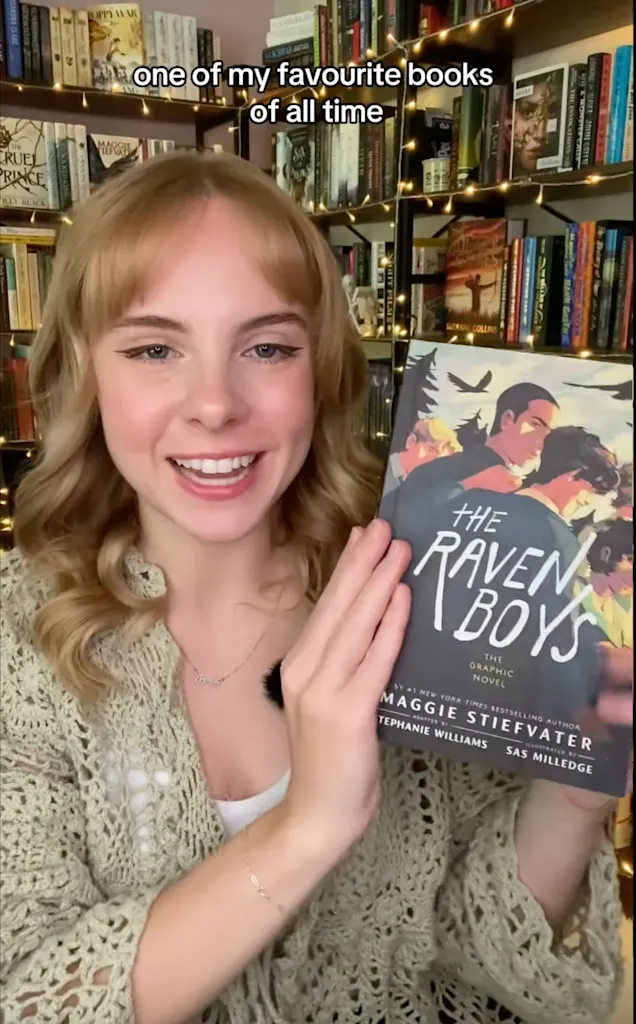

Daphne LaPlante, 25, a video editor in Austin, Texas, posts videos to TikTok, Instagram and elsewhere proclaiming her love of books. She got her start on the app in 2021, in her final year of college.

Scrolling on the popular video app, she realized that other young people were also hungry for conversations about books. One of her favorites, the fantasy novel Six of Crows, was being made into a TV show, she recalled “and I had nobody to talk to about it.” So she turned on her phone’s camera and hit record. Soon her videos began detailing what she’d read each month, and before long she was recommending books. After a while, publishers took note and started sending her advance copies of new titles.

LaPlante now has more than 40,000 followers on TikTok and over 30,000 on Instagram, and jokes that she has become a “micro-influencer” in the corner of the social media site known as BookTok. Born during the pandemic, it has become so influential that it has both crowned new hits and turned a few backlist books into best-sellers. One industry analysis suggests that BookTok has changed behaviors: In 2021, the year it started gaining momentum, book sales rose in the U.S. by 9%, to 825.7 million copies, the most since the research company NPD BookScan began tracking sales data in 2004.

“I think a big part of getting people into reading is community,” she said.

For the past year-and-a-half, LaPlante and a friend have also recorded a podcast called Rereading the Revolution, about their love for 2010s-era young-adult dystopian fiction, epitomized by The Hunger Games and similar titles. “There are a lot of people, like me, who read those and were obsessed with them as a kid,” she said.

‘I don’t want to eat the f***ing salad’

If he’d had a mobile phone 25 years ago, Hendrick, the Irish educator, might well have been on BookTok, forcefully recommending his favorite literature, history and philosophy books. He recalled getting lost as a young man in The Great Gatsby, reading it cover-to-cover in two days. He has since read and taught it many times, but wonders: If he was 16 now, what incentive would he have to read such a book, given all the social forces in teens’ lives? With so much “easily attained dopamine” via social media, video games, movies and elsewhere, why would anyone go through the effort?

He thinks about what books must look like to his six-year-old daughter. “She can read,” he volunteered. “She’s really clever, but she just doesn’t want to because everything else is so ….” After considering it for a second, he finally said, “She’s in McDonald’s and I’m telling her to eat the salad, and she’s going, ‘I don’t want to eat the f***ing salad. There’s all these chicken nuggets. Why would I do that?’”

To bring back reading, he said, schools may very well have to do more than just improve instruction and reading stamina and find a few tasty books. They’ll have to get mobile phones out of classrooms, he said—actually, buying a phone for a 10-year-old “should be outlawed,” he said. Many states and schools, to their credit, are getting the message and banning phones for much of the school day. But they may also have to consider a back-to-basics approach that treats reading as an indicator of public health.

“With cars, we mandated seat belts,” he said. “We mandated speed limits. It may be the case that we need to say, ‘Kids have just got to read for an hour in silence on their own. That’s just it—in the same way you’ve got to eat certain vegetables.’”

In 20 years, Hendrick predicted, we’ll likely discover that reading and, more broadly, deep cognitive focus, offer the same kinds of benefits as exercising or a balanced diet. We’ll look back on this decade, he said, with its easily attained dopamine, its endless mental chicken nuggets and distractions, and realize, “We were weaponizing mental health problems.”

A quarter-century ago, Hendrick recalled, after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the novelist Norman Mailer was unequivocal when asked about their significance. “He said, ‘It’s going to take us 10 years to figure this out. Call in the novelists.’ His thing was, we need to get the writers in to make sense of this.”

People, in other words, need books. No matter how advanced our digital media have become, nothing can replace the depth of understanding they afford.

“For me, when I read Shakespeare or The Sound and the Fury or [James] Joyce, I was finding out what it meant to be alive,” said Hendrick. “My struggles were the struggles of other people. And I was learning about ethics and morality. Where are we going to end up without that?”

This article was also published at The74Million.org, a nonprofit education news site.