- | 9:00 am

LinkedIn turns 20: An oral history of an unlikely champion

Social media, for work? The world was skeptical. But 20 years and a few white-knuckle moments later, LinkedIn has become synonymous with networking—and it’s got more momentum than ever.

When LinkedIn launched, on May 5, 2003, it wasn’t a given that it would thrive. Born during the doldrums after the original dotcom bust, it arrived at the same time as a flurry of other social networking upstarts, most of which quickly fizzled. Its emphasis on members’ professional lives rather than personal pursuits was seen by some as a strategic blunder. Even the notion of posting your résumé in public was jarringly unfamiliar and likely to be taken as an act of disloyalty.

Rather than falling victim to preexisting assumptions, LinkedIn changed them. Eventually, it was not having a LinkedIn profile that was perceived as a weird career move. As the pandemic and its aftermath have reshaped work, the service has both reflected that new world and equipped workers and employers to succeed in it. Its emphasis on professionalism also offers a safe harbor from more toxic and polarizing social platforms.

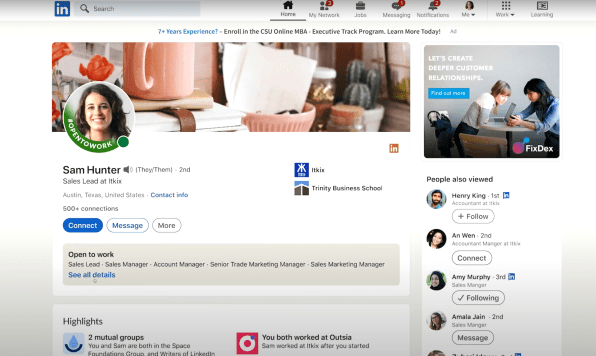

LinkedIn hasn’t escaped the current tech downturn—in February, it announced layoffs—but it’s a rare example of a company seeing its greatest success after being bought. When its stock plunged by more than 40% in 2016, Microsoft swooped in and snapped it up for $26.2 billion—but then let it continue to chart its own destiny. Today, more than 4,500 job applications are submitted and 8 hires are now made every minute on the platform. Its revenue surpassed $14 billion in the past 12 months, close to quadruple the figure at the time of acquisition.

The lesson? “The less exciting turtle does win the race sometimes,” says Reid Hoffman, the company’s cofounder, original guiding light, and first CEO, who went on to become one of the most influential people in Silicon Valley. “We just kept going.”

To tell LinkedIn’s improbable story, we talked to dozens of eyewitnesses, including founders, key employees, early users, independent observers, and current executives. Their comments have been edited for length and clarity. For more on the company’s impact, read our companion oral history on how it turned its alumni into one of the tech industry’s most impressive startup factories.

Additional reporting by Yasmin Gagne, Jared Lindzon, Megan Morrone, and Mark Sullivan

IN THE BEGINNING (1997–2003)

Before LinkedIn, there was SocialNet. Cofounded in 1997 by Reid Hoffman—who held a master’s in philosophy from the University of Oxford and had helped develop online communities for Apple and Fujitsu—the proto-social network had a few business-oriented features. But they weren’t the main point.

Hoffman: The natural thing, when everyone starts doing social products, is they always go to dating. We did that with SocialNet. We focused on, “How do we build a much better dating engine?” And we added the professional networking as an afterthought.

Patrick Ferrell, cofounder, SocialNet: Reid and I would sit some nights with our glasses of cabernet, and we would argue about various attributes of social networking until 2 in the morning.

Allen Blue, SocialNet director of product design, LinkedIn cofounder: It was a weird time, when [the web] was open to anyone who wanted to participate in it. Everything was based on HTML 1, so you could jump in pretty easily. I’d built websites and things for the Stanford Department of Drama, so when I got a call from a friend who knew Reid, I ended up joining [SocialNet].

Ferrell: We were a little too early. We had a non-clever board. I don’t want to be too critical of them, but . . . if we had a more aggressive and clever board, I think that would have helped.

When SocialNet didn’t take off, Hoffman became COO of budding platform PayPal, where he was on the board. eBay acquired it in 2002, for $1.5 billion. Hungry to start a new company, Hoffman quit and pulled in friends to brainstorm possibilities—including a site focused on business networking. The startup economy was still struggling to recover from the bursting of the original dotcom bubble.

Mark Pincus, founder of early social network Tribe.net and Zynga: We were in what I call the nuclear winter for the consumer internet, especially in San Francisco. It was a quiet, dark, sad place here.

Mark Jeffrey, cofounder of social network ZeroDegrees, launched in 2003 and sold to IAC in 2004: It sort of felt like the internet wasn’t really a thing. That it wasn’t really more important than the fax machine.

Hoffman: While I thought, at SocialNet, [that] our dating product was better [than existing dating sites], it wasn’t 10x better. And yet there was this huge new need where no one was operating and that was a much better place to be. People have their careers for their entire lives.

Blue: Reid had us over to his apartment on Castro Street [in Mountain View, California], above a pizzeria. We talked over a bunch of ideas.

A LOT OF BLOGGERS WOULD SAY, “LOOK, YOU GUYS DON’T HAVE A FUTURE.”

Keith Rabois, LinkedIn VP of business and corporate development (2005-2007): One was basically a way of creating an archive of all your memories, of all society’s memories. And it would be buried and then opened in 10 or 20 years. Fortunately, he didn’t do that one.Hoffman: We kicked around different things, but I’d say that we started with the LinkedIn idea and nothing was even remotely as good. So we came back to it.

Eric Ly, LinkedIn cofounder: The basic premise was to keep track of your network. Those of us who were in the startup world, there was so much job mobility. When you wanted to figure out where one of your friends was, in case you wanted to pull them into your startup, having that information was very valuable.

Hoffman and his LinkedIn cofounders—Blue, Ly, Konstantin Guericke, and Jean-Luc Vaillant—hashed out their plans in the midst of a social networking boomlet, amid other contenders such as Ryze, Tribe.net, ZeroDegrees, and Friendster.

Adrian Scott, founder, Ryze: “[Ryze] wasn’t just a friends site. It was built to support business networking. [But] it wasn’t just a purely antiseptic, serious business environment; you would list your interests as well.

Jeffrey: Ryze [had gone] very wide among me and my friends. But Friendster went very wide in the more open world. And that was when all of us went, “Wow, there’s something here.”

Pincus: [Tribe.net was] Craigslist meets Friendster. Why wouldn’t you want to see a picture of the person who’s coming over to get your couch or be your roommate?

Guericke: A lot of bloggers would say, “Look, you guys don’t have a future. Once Friendster allows you to put in where you’ve worked and when, then there’s no room, because Friendster is a hundred times as big as you.”

Hoffman and Pincus teamed up to pay $700,000 for a patent associated with SixDegrees, which by some definitions had been the first true social network. Launched in 1997, it was dormant by 2000.

Andrew Weinreich, founder, SixDegrees: The original vision of SixDegrees was we would index people’s relationships in a single database. We wrote a patent on what a social network was, and, specifically, how a social network is formed.

Pincus: Reid came to me and said, “Mark, we have to buy this patent on social networking. It’s going to be important and fundamental.” He made the case. And I said, “You’re right.”

Hoffman: Part of why Pincus and I bought it is that we thought that there was going to be an entire explosion of new services that would be modeled on SixDegrees. We were bidding against—I guess it’s safe to say now—Yahoo. And we were worried that it would be used as a weapon to quell entrepreneurship.

Pincus: There were articles written saying that Reid and I were patent trolls and we were going to hold up the whole industry. And you know, I think history showed that we bought it for the right reasons. We wanted to protect the industry, and we never did anything with it.

At first, the LinkedIn network consisted only of the company’s initial employees. It grew—slowly at first—from there.

Hoffman: It all started with 13 people out of an office in Mountain View. They were generation zero.

Laurie Thornton, founder, Radiate PR, LinkedIn’s first public relations firm (2003–2007): You couldn’t get in unless you received an invite, and you could meet other people only through the people you knew.

Adam Edgmond, LinkedIn (2010–2013), beta tester, technical producer: I’m friends with [original LinkedIn web developer] Chris Saccheri. He reached out and said, “Want to check out a beta test? You might be [one of] the first humans to get in.” It was pretty rudimentary.

Tina Mitiguy, who was trying to find a marketing job after earning an MBA: I had an interest in healthcare. A friend of mine from college said, “Hey, if you’re looking for a job, this is where you should upload your profile.” So I did. There was a bit of a downturn, and it occurred to me that I was never going to get a job sending résumés out.

Kevin Werbach, founder, the tech consultancy Supernova Group, and one of the first few hundred LinkedIn members: I joined because we were all exploring new social networking platforms back then. We knew something was developing.

Rafe Needleman, whose June 2003 column on LinkedIn for Business 2.0 magazine was a critical early piece of media attention: Kevin Werbach sent me a request and I was flattered because he’s a really smart guy. It seemed more professional than the other stuff that was out there, so I gave it a shot.

When another LinkedIn member found Mitiguy through shared connections and ended up offering her a job in June 2003, weeks after the site’s launch, it was so novel that it received coverage in The Wall Street Journal and other publications.

Mitiguy: The job was at a startup providing personal health information in case of emergencies, and it seemed like just the right fit for me. I felt very fortunate.

GETTING BIG, CHANGING PERCEPTIONS (2004–2006)

Early on, LinkedIn allowed new members to invite all their contacts to join the network with a few clicks—greatly boosting its vitality but leaving some people with a spammy impression of the service.

Russell Glass, LinkedIn VP of product (2014–2017); CEO, Headspace Health: When LinkedIn figured out that you can incentivize people to bring their contacts in and help them join the network, that was kind of a game changer in the growth curve.

Rabois: Reid was the one who made the decision to invest a team in [enabling] uploads from Microsoft Outlook address books. At the time, almost everybody, certainly in Silicon Valley, ran on Outlook email. That is the way we did business.

Thornton: In the early months, pushback came in the form of “I don’t want to take my Outlook contacts and expose myself and those in my network online. Why would I want to do that?”

Adam Nash, LinkedIn VP (2007–2011); Wealthfront CEO (2013-2016), cofounder, Daffy: Your relationships are a big asset in your career, and we could help people a lot more if they were better connected. The flip side was that sending a LinkedIn invite to someone you didn’t mean to send it to could really be a negative experience.

Guericke: We would send out a reminder that your invitation was going to expire. And some people were like, “Oh yeah, I forgot to accept this invitation—I meant to, I was just going into a meeting.” And some were like, “That’s annoying!”

Originally, members’ profiles were visible only to other members. In 2006, LinkedIn boosted growth by making user information public and allowing it to be found via search engines—giving people who weren’t ardent business networkers a reason to join the service.

Rabois: Normal people were aware that friends, family, and potential dates would be googling them. So it made it a little bit more intuitive to a normal person why a LinkedIn profile could be valuable.

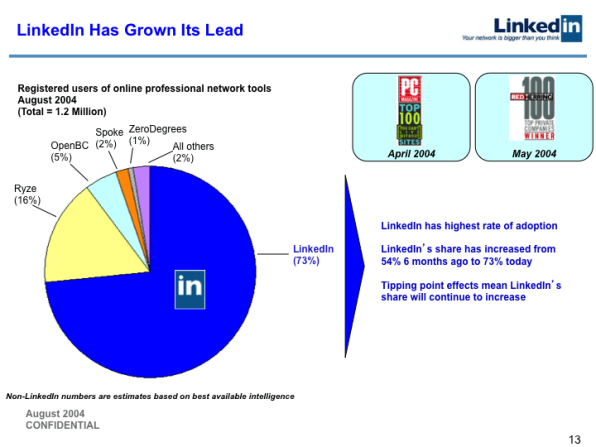

The service grew from 30,000 users in October 2003 to 3.8 million in October 2005 to 8 million in April 2006. It launched its first major monetization efforts—such as charging employers $95 per job listing and offering premium accounts that allowed recruiters and others to contact members they weren’t connected with—and revenue jumped from $1.1 million in 2005 to $32 million in 2007. But even as the service scaled, there was skepticism about the very concept of a business-focused social network.

Hoffman: If you wind all the way back to 2003, it was like, “Oh, aren’t you advertising disloyalty if you put your [résumé] online?”

IF YOU’RE SOMEONE A LOT OF PEOPLE WANT TO CONNECT WITH, YOU HAVE A DIFFERENT EXPERIENCE THAN A TYPICAL USER.”

David Sze, partner at venture firm Greylock, which led LinkedIn’s Series B funding round in 2004: A big moment early on was when major banks limited access to LinkedIn on company-owned computers. They said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, we don’t want anyone on this. We don’t want anyone out there with their profile out in the world.”Hoffman: Part of the thing that LinkedIn was doing was getting people psychologically comfortable with having a professional identity. Because pre-LinkedIn, a public professional identity was something for bloggers, or a very small number of people who’d set up a website, or journalists.

Arvind Rajan, LinkedIn VP, managing director (2008–2014); cofounder, Cricket Health: I remember there was some interview with Mark Zuckerberg where he said that having a separate professional and personal identity reflects a lack of integrity. A lot of people thought that was the case.

Kay Luo, LinkedIn senior director of corporate communications (2006–2010): For many years, LinkedIn never had photos on the website. And there were two camps in the company on that. There was the camp that said, “No, if you put photos, it’s going to turn into a dating site.” And then there was the other side that felt like it’s part of your professional reputation and brand.

Ly: If we introduced that feature too early, it could have gone wrong in so many different ways. It was carefully introduced at the right time.

Nash: We really nudged people: “Not you and your friend at a beach party. You want a headshot.”

Jay Kreps, LinkedIn engineer (2007–2014); cofounder, Confluent: Now it’s become such a staple that people call in professional photographers to update their headshots for LinkedIn specifically.

Not everyone instinctively grasped LinkedIn’s utility or used it as intended.

Chris Selland, founder, research firm Reservoir Partners and veteran business development executive: There was this whole thing for a while where people called LIONs [LinkedIn Open Networkers] would just basically blast everybody and say, “Connect with me.” I remember

that almost killed it for me. It’s like, “I don’t know you. What’s the value?”

Luo: They were basically super networkers that tried to connect with as many people as possible, and that’s really not how to use LinkedIn.

John Kovacevich, marketer and longtime LinkedIn power user: Early on, I made the decision to only [connect] with people that I’d actually worked with and not accept invitations from random strangers. The weirdo growth hackers who rack up connections like video-game points don’t make any sense to me.

Luo: We had what Reid called “the rock-star problem.” If you’re someone a lot of people want to connect with, you have a different experience than a typical user. And it would probably be a fairly spammy, low-value proposition to you.

Guy Kawasaki, tech-industry evangelist, author, and influencer: I understood why people would want to get to me, but I didn’t have the need to get to millions of people, not initially, because I wasn’t trying to apply for a job. So it was a little asymmetric.

Luo: Guy was not shy about bashing LinkedIn. So one of the first things I did was help him draft a post on 10 ways you can use LinkedIn. He ended up publishing that post on his blog, and it became the most-read post he had ever published.

Kawasaki: I completely changed my mind.

BUILDING A CULTURE—AND A BUSINESS (2007–2010)

In February 2007, Hoffman handed the CEO role to former Intuit executive Dan Nye, but he took it back in late 2008. In June 2009, Hoffman was succeeded by Yahoo alum Jeff Weiner, who sought to elevate the company’s purpose.

Weiner: Like many others, I thought of LinkedIn primarily as a Rolodex and networking tool. After the opportunity to become CEO [came up], I started to learn more and was struck by the enormity of the potential of the platform as a means to facilitate the flow of human, intellectual, and working capital.

Ryan Roslansky, LinkedIn (2009–present), chief product officer, CEO: When Jeff joined LinkedIn, he called and asked me to join him as his first hire. It took him maybe 10 minutes to explain that if you can digitally map all the professionals in the world, and all the companies and jobs and skills, you can create meaningful economic opportunity for every member of the global workforce.

Weiner: Shortly after I joined, we implemented a framework called “Vision to Values.”

Kreps: I was actually very suspicious of it when he came in. I was like, “Why is this guy spending all this time talking about values? We just need to figure out how to ship the software faster.”

Charlene Li, founder, Altimeter Group; chief research officer, PA Consulting: Every time I met with somebody from LinkedIn, I would ask, “Why did you decide to do this?” And they would always bring it back to purpose and mission and values. I’ve never seen a company do that so consistently.

With more than 30 million members at the time of Weiner’s arrival, the company had attained enough scale to build out its business model in earnest. In 2013, it reached $1.5 billion in revenue, with more than half coming from job listings and 20% from paid member subscriptions. The remainder came from advertising.

Kreps: [In the early days], it was like, “Okay, these social networks, they’re kind of interesting, but you’re never going to make any money.”

Rajan: Our most important stakeholders were members. Ninety-five percent of them would never pay us a dime. And so we were really, really clear that if there were any ways that we had to make money, they had to be value accretive to the free member. That meant we turned down lots of revenue opportunities back in 2007, 2008.

DJ Patil, LinkedIn chief scientist (2008–2011), chief data scientist of the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy (2015–2017): People just wanted us to sell the database. And we could have. There’s nothing legally preventing you from doing that. There was an ethical and moral obligation to the people that we served.

Dan Shapero, LinkedIn (2008–present), VP, chief business officer, chief operating officer: When I joined, the conversation at LinkedIn was something like, “Seems like recruiters really love LinkedIn. Maybe we could build something that would help them. Seems like small-business owners really love LinkedIn. Maybe we could build something just for them.”

Kreps: By and large, all of those efforts succeeded and turned into big businesses.

Edgmond: Someone had built a hack-day project so that if someone wanted to pay us to send a sponsored message, they could. I put that on a server and hosted paid messages to millions of users. The stuff we were using to make beaucoup bucks every year came out of a little toaster that fit under someone’s desk.

Tim O’Reilly, technologist and founder, O’Reilly Media: The thing that was most important about LinkedIn was that it found a business model for social that really worked, and it wasn’t [just] advertising.

The company started to think seriously about giving members stuff to do beyond racking up connections and hunting for jobs, incentivizing them to visit more than just occasionally.

Dan Roth, LinkedIn (2011–present), executive editor, editor-in-chief: Your professional reputation lived on LinkedIn. The idea of content showing up there as well seemed very foreign.

Shannon Brayton, LinkedIn (2010–2020), VP of communications, CMO, CMO and partner at VC firm Bessemer Venture Partners: There was no content. People weren’t posting anything. I remember at one meeting in 2010, we were looking through the feed and basically every single post or action was from a LinkedIn employee.

Roslansky: We partnered with Twitter to help people send their tweets into LinkedIn to create some liquidity.

Akshay Kothari, LinkedIn (2013–2018), product lead, VP of product, head of LinkedIn India; cofounder, Notion: Then Twitter shut it off because they were trying to keep [tweets] to their products. And what ended up being a crisis for LinkedIn ended up becoming a huge opportunity, because that pushed us to really drive our own content.

IT WAS AMAZING TO SEE PEOPLE [REACT] WHEN THEY SAW SOMEONE LIKE RICHARD BRANSON OR BILL GATES WRITING ON LINKEDIN.”

Roslansky: We tried to find leaders across the world to share their knowledge. And that kick-started this idea of LinkedIn being more of a vibrant network than just a place where you create your résumé and your profile.Roth: One thing [people] liked is that we said, “We’re not going to edit you. You can do this on your own. We’ll build you a big following.” A big yes for us was Richard Branson.

Richard Branson, founder, The Virgin Group: I saw it as a great opportunity to connect with people, highlight the work being done across the Virgin Group, shine a light on global issues I am passionate about, and share my thoughts.

Arianna Huffington, founder, The Huffington Post and Thrive: I started posting on LinkedIn in 2012, around the same time I joined Richard Branson’s B-Team, a group he created to get business to prioritize people and the planet and not just profits. I wanted to be part of that conversation.

Roth: We delayed the launch because we were hoping to get Oprah. And we didn’t.

Beth Kanter, trainer, author, and early LinkedIn influencer: I was out to dinner, and all of a sudden my phone blew up with text messages saying, “Hey, Conan O’Brien is talking about you.” At the time, on my profile [photo], I had this big red cowboy hat. He did this hilarious bit about how he was going to get to the top of the LinkedIn influencer list and he said, “There’s this woman, Beth Kanter, with a Randy ‘Macho Man’ Savage red hat. If she can get all these followers, then I can get all these followers, and I’m going to put a red hat on my profile. But it’s going to be me with a red hat standing in the palm of the Pope next to [several U.S. presidents] with red hats on.” It became my claim to fame. And I got, and I still have, more followers than he does.

Blue: It was amazing to see people [react] when they saw someone like Richard Branson or Bill Gates writing on LinkedIn. They were surprised to see these voices, writing in a way native to the network.

Branson: I remember celebrating with the team on the day I became the first person to hit 1 million followers in 2012.

Along the way, LinkedIn also had to rethink itself for the smartphone era that dawned with the iPhone’s introduction in 2007. Like many companies that had built their products for use on PCs, it stumbled at first.

Kothari: There was a big transition to mobile that was an existential threat because so much of the advertising business was display advertising on the desktop.

Rahul Vohra, LinkedIn mobile products (2012-2014); founder and CEO, Superhuman: Facebook famously messed this up by building their entire mobile app in, essentially, HTML before realizing that wasn’t going to cover it, and then they had to rewrite the whole thing again. The LinkedIn mobile app was actually even worse.

Erran Berger, LinkedIn VP of product engineering (2009–present): We could see that greater than 50% of our members’ usage of LinkedIn was going to be on mobile. And yet so much of our R&D talent was people who grew up developing web applications.

Tomer Cohen, LinkedIn (2012–present), head of mobile product, VP of product, chief product officer: LinkedIn was a desktop-first company since it was established in 2003. And we literally had hundreds if not thousands of pages being built differently than if we came from mobile. Mobile was a very focused, concentrated experience. It didn’t allow for a lot of complexity.

Berger: We had to completely reimagine how we build products here, from the way that we design them through the infrastructure to the type of people that we have on our teams. It was maybe the most intense period I can think of in my time here, a full year of rebuilding everything from the ground up.

Cohen: Within two or three years, most of LinkedIn [usage] became mobile.

AN IPO, A STOCK DROP, AND AN ACQUISITION (2011–2016)

On May 19, 2011, LinkedIn became the first social media company to IPO. The stock more than doubled on its first day of trading, reaching a market cap of $9 billion. But it ended up spending only a half decade as a public company.

Weiner: During the first internet boom, I had seen far too many examples of employees becoming distracted by their company’s IPOs, with negative consequences. I wanted to ensure that didn’t happen to us.

Brayton: We went public at 1 o’clock or whatever on the East Coast, and we all took a flight home that night to make sure we were back in the office the next day. We wanted to make sure people felt like, “Okay, that was a moment in time, but now we’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Rajan: When we went public, the month or two afterward felt no different than the way it was before we had gotten public because we were just a really well-run, tight ship.

Sze: A company journey’s doesn’t end when there’s a IPO. There was definitely a little malaise about, “Okay, can you continue to grow? Is there another chapter here? Will it continue to be an interesting business? Should it be a public business?” All those kind of things. And we could see the value that we were creating.

A moment of truth occurred when LinkedIn’s stock plunged by 43.6% on February 5, 2016, after the company forecasted earnings far short of Wall Street expectations (due to the sunsetting of a sales feature called Lead Accelerator, foreign currency issues, ad challenges, etc.). Eleven billion in market value evaporated, and LinkedIn reassessed its prospects as an independent entity.

Brayton: Jeff and I did a lot of strategizing [after the drop]. He showed up two days later at our regular scheduled all hands and completely nailed the message to the company. He basically said, “We’re not 40% less valuable than we were a day ago. Markets do what they do.” He gave this incredible, impassioned speech.

Glass: I remember Jeff’s talk to the company—I remember the seat I was sitting in, the message, the tone, the narrative, the whole notion of “We are the same company we were yesterday.”

Kothari: We could see our net worth go down, but we also realized, “Hey, we still are here to create jobs for other people. I can create economic opportunity.” It kept us going.

Brayton: We got a bunch of calls from other companies interested in potentially buying us.

Hoffman: It might have had some psychological influence on our receptivity to [being acquired]. We’d gotten a lot of interest over the years.

On June 13, Microsoft announced that it was buying LinkedIn—which had 433 million users at the time—for $26.2 billion.

Satya Nadella, CEO, Microsoft: I’m a deep believer in democratizing productivity and communication tools, because that’s what empowers people to be able to be great at their job, acquire new skills, and grow their economic opportunity. Reid, Jeff, and I discussed all of this for a while, and the potential of the two companies was something that I’d been thinking about for a long time.

Sze: We spent a bunch of time at the operating levels with the teams. It felt really good—the alignment of mission, style, and goals.

Josh Graff, LinkedIn (2011–present), various executive roles related to global operations, VP of global enterprise: When the acquisition was announced, there was a combination of anxiety and curiosity.

Tanya Staples, LinkedIn (2015–2022), senior director of content, VP of product: Like “Why Microsoft? Why not Google, or insert-any-other-company-here?”

A LOT OF TIMES, LARGE COMPANIES BUY OTHER COMPANIES AND THEY WANT TO INTEGRATE THEM.”

Hoffman: We said, “Hey, our missions are friends, right?” Microsoft‘s mission is to empower every individual and organization to do their best work. LinkedIn’s mission is to empower every individual to have the maximum deployment of their talent for their work and their career. It’s like peanut butter and chocolate.Roslansky: A lot of times, large companies buy other companies and they want to integrate them.

Nadella: I knew we needed to take a different approach. We made the decision early that LinkedIn [would] retain its distinct brand, culture, and independence.

Staples: Once we became part of Microsoft and saw what Satya was doing and how he was leading the company, it did very much feel like a fit.

Brayton: I think we ended up adopting their paternity policy or something because it was better than ours. But honestly, pretty much everything stayed the same.

BEYOND THE “BLUE MAN IN A SUIT” (2017–PRESENT)

Now part of Microsoft, LinkedIn began the process of reimagining itself for a new world of work. Then COVID-19 hit—right before Roslansky succeeded Weiner as CEO. Today, LinkedIn’s momentum shows no sign of peaking.

Meg Garlinghouse, LinkedIn VP of social impact (2010–present): I don’t think that, six or seven years ago, [everyone] thought [LinkedIn] was a place they should be. They weren’t sure that they belonged.

Melissa Selcher, LinkedIn (2016–present), VP, SVP, chief marketing and communications officer: We did a lot of qualitative research along with the quantitative, and someone said, “LinkedIn, to me, feels like a faceless blue man in a suit.” It’s funny when someone says that. But you’re also like, “Ouch, that hurts.” And then you’re like, “I can kind of see it.”

Sarah Alpern, LinkedIn (2007–2013 and 2017–present), senior designer, user experience design director, VP of design: We had this internal rallying cry: “We are not a faceless blue man in a suit! We are so much more.”

Cohen: Gen Zs bring their full selves to work, so being able to tailor their profiles to showcase all dimensions of themselves is really important.

Selcher: We own this responsibility to extend the definition of “professional” to include all kinds of professionals and success. “Professional” should include talking about mental health and sharing your diversity journey.

Cohen: Now, some of our most engaged segments are first-line [workers], entry roles, students, Gen Z. Fifty-five percent of our sign-ups are coming from those segments.

International usage has also helped drive recent growth—and opened up opportunities for even more expansion.

Cohen: Close to 80% of our members are outside of the U.S., engagement is predominantly outside of the U.S., growth is predominantly outside of the U.S. So in many ways, we are much more international than we are U.S. focused.

Graff: India is our fastest-growing market. Members are highly engaged. We’re on track to be a hundred million members very soon. And if you look at India broadly, there’s a workforce of half a billion people. There’s a middle class larger than the whole population of Australia.

Roslansky: Three days ago, we had our largest sign-up day in the history of LinkedIn, which is very rare for a consumer internet company that is 20 years old.

Cohen: We saw a surge in usage [during the pandemic]. Almost overnight, [people] didn’t have that workplace environment like they had before.

Mohak Shroff, LinkedIn (2008–present), engineering lead, director of engineering, VP of engineering, senior VP of engineering: North of 50% of jobs on our platform now indicate themselves as being open to remote work.

The company defines itself in loftier terms than a mere social network, though users continue to embrace it as such.

Roslansky: We don’t view ourselves as a social network. We are a platform that exists to create economic opportunity.

Teuila Hanson, chief people officer (2020-present): If you ever get to an impasse or are in a situation where you need to make a decision and you’re not quite sure which way to go, you ask, “Is this decision going to create economic opportunity for every member of the global workforce?”

Kawasaki: I don’t know if the LinkedIn people would like me saying this, but I think that LinkedIn is simply the best social network.

Branson: It continues to play a crucial role in how I communicate with leaders, customers, peers, employees, and entrepreneurs.

Kreps: On Twitter, the thing that makes people popular is amplifying the worst thing that somebody else said. That creates this cycle of negativity. The worst thing on LinkedIn is probably just some stupid article about stuff you do at the office.

Kothari: In the last few years, when things have really gone out of control [on other platforms], LinkedIn has been a safe place for people to write. It’s always had this professional filter. Sometimes, people may feel like it’s kind of boring, but I think it’s actually helped.

![2008: 13 million LinkedIn members [Photo: courtesy of LinkedIn]](https://images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_562)