- | 8:00 am

What the web looked like in 1994, the year it became the internet

The earliest web pages are a far cry from today’s cyber wastelands.

What was the World Wide Web like at the start? Long before it became the place we think and work and talk, the air that we (and the bots) now breathe no matter how polluted it’s become? So much of the old web has rotted away that it can be hard to say; even the great Internet Archive‘s Wayback Machine only goes back to 1996. But try browsing farther back in time, and you can start to see in those weird, formative years some surprising signs of what the web would be, and what it could be.

In 1994, the modern Internet (which you always capitalized and sometimes called just “Internet”) was itself only 11 years old, mostly the domain of researchers and hobbyists and hackers and geeks, who used an array of globe-spanning services for communicating (email and Usenet newsgroups, in addition to local BBS and IRC) and for downloading files via FTP and for searching for documents and texts with services like Gopher and WAIS.

The Web was a relatively new addition to the mix that tied a few of these systems together, with a twist. Tim Berners-Lee, a scientist at CERN in Geneva, had built it in 1989 to organize the lab’s sprawling pool of physics research by combining three technologies he’d invented: a language (HTML), a protocol (HTTP), and a way to locate things on the network (URLs). Now, the Web was growing rapidly, in part because it was free. In April 1993, shortly after the University of Minnesota decided to charge licensing fees for servers that used its Gopher protocol, managers at CERN chose to put the Web’s source code in the public domain and make it available on a royalty-free basis. That opened it to anyone who wanted to set up their own server.

The Web was also increasingly popular because it was easy to use and to look at, and even relatively easy to make. Instead of navigating folder hierarchies and plaintext files, users could browse pages with clickable hypertext. Now, anyone who could use a keyboard and mouse could traverse cyberspace. And by January 1994, when then-Vice President Al Gore presided over a summit at UCLA to hail the possibilities of the new “information superhighway,” millions of people suddenly had a slick new ride.

This story is part of 1994 Week, where we’ll revisit some of the most interesting and confounding developments in tech 30 years ago.

The previous year, Marc Andreessen, a fresh graduate of the University of Illinois, released “Mosaic” together with Eric Bina, an engineer he’d met at the university’s National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NSCA). It was the first major “graphical” web browser, capable of displaying images within pages rather than requiring separate windows. In November, they ported it to Windows and Mac computers. Suddenly, out on the austere frontier of text-only how-tos (see the first Web page), researchers’ websites, and community pages that had spilled over from Usenet and BBS, colorful, eye-popping pixels began to appear. With images and and an easy-to-use interface, Mosaic was turning the internet into a new medium, what Berners-Lee called “hypermedia,” displaying a universe of information that had previously only appeared on interactive CD-ROMs like Microsoft Encarta. Unlike CDs, however, the Internet was never-ending and always changing. And increasingly, it looked less like a computer terminal and more like a glossy magazine.

By December, Mosaic was being called “the first killer app of network computing,” by the New York Times. (Gore deserves some credit here: it was ”the Gore Bill” of 1991 that led to the NSCA.) At first, “a few people noticed that the Web might be better than Gopher,” the internet engineer Bob Metcalfe said later. Then came Mosaic: “Several million then suddenly noticed that the Web might be better than sex.”

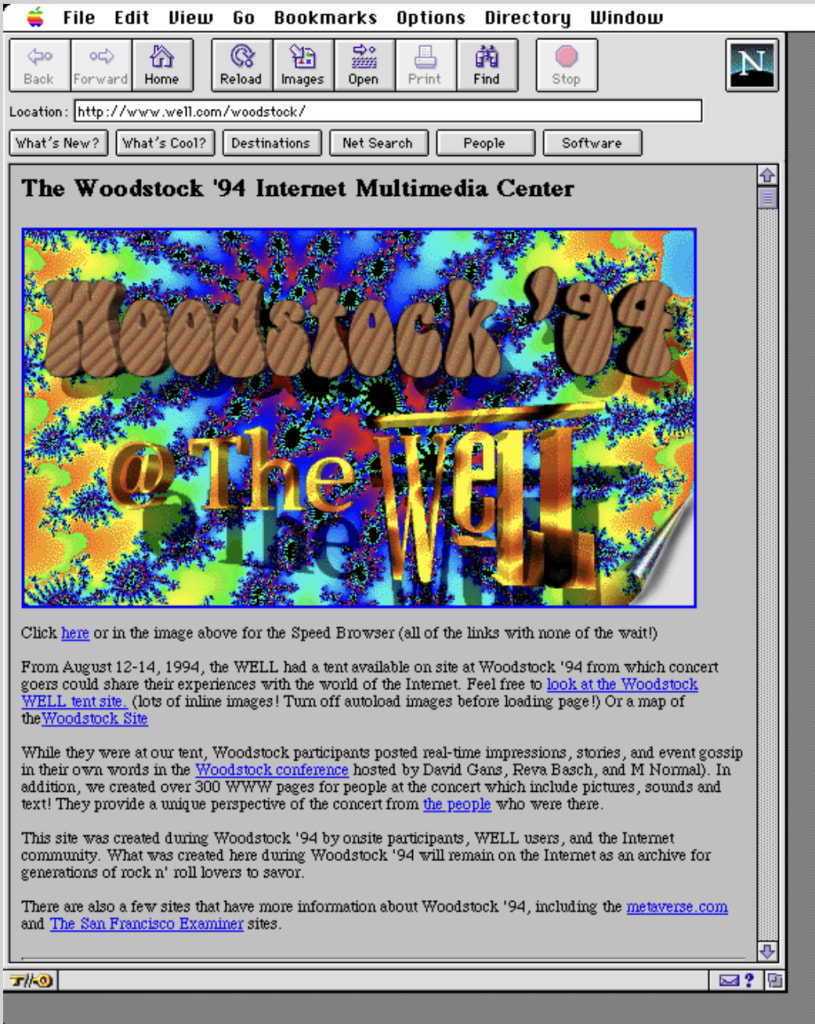

It was, CERN declared, “the year of the Web.” Throughout 1994, millions of PC users began venturing online for the first time, many of them with Mosaic. And for the many who dialed-in through the sanitized, cloistered portals of America Online (AOL), Prodigy, or Compuserve (all of which would offer their users web browsers by the end of the year), the Web was a revelation. By the time of the first World Wide Web Conference in May 1994—an oversubscribed gathering in Geneva that some dubbed “the Woodstock of the Web”—it was already too late to clarify: “the Web and the Internet are now often thought of as synonymous,” one attendee observed. Two months later, “The Internet” would land on the cover of Time.

It’s hard to say precisely when things changed online. Many point to September ‘93, when AOL users first flooded Usenet. But the web entered a new phase the following year. According to an MIT study, at the start of 1994, there were just 623 web servers. By year’s end, it was estimated there were at least 10,000, hosting new sites including Yahoo!, the White House, the Library of Congress, Snopes, the BBC, sex.com, and something called The Amazing FishCam. The number of servers globally was doubling every two months. No one had seen growth quite like that before. According to a press release announcing the start of the World Wide Web Foundation that October, this network of pages “was widely considered to be the fastest-growing network phenomenon of all time.”

As the year began, Web pages were by and large personal and intimate, made by research institutions, communities, or individuals, not companies or brands. Many pages embodied the spirit, or extended the presence, of newsgroups on Usenet, or “User’s Net.” (Snopes and the Internet Movie Database, which landed on the Web in 1993, began as crowd-sourced projects on Usenet.) But a number of big companies, including Microsoft, Sun, Apple, IBM, and Wells Fargo, established their first modest Web outposts in 1994, a hint of the shopping malls and content farms and slop factories and strip mines to come. 1994 also marked the start of banner ads and online transactions (a CD, pizzas), and the birth of spam and phishing.

“I think the market is huge,” Martin Nisenholtz, an advertising executive at Ogilvy & Mather, told Time. Among his guidelines for marketing to the Net: “Intrusive E-mail is unwelcome.” Also: “It’s O.K. to post an ad for a used computer, for example, in a newsgroup called comp.system.mac.wanted, or to sell flowers in a corner of the Net marked florist.com.” Tell that to today’s digital advertisers: In 2023, spending on programmatic advertising globally was estimated to reach more than $300 billion. In 2021, a Comscore analysis estimated that $2.6 billion of that was spent on websites pushing misinformation.

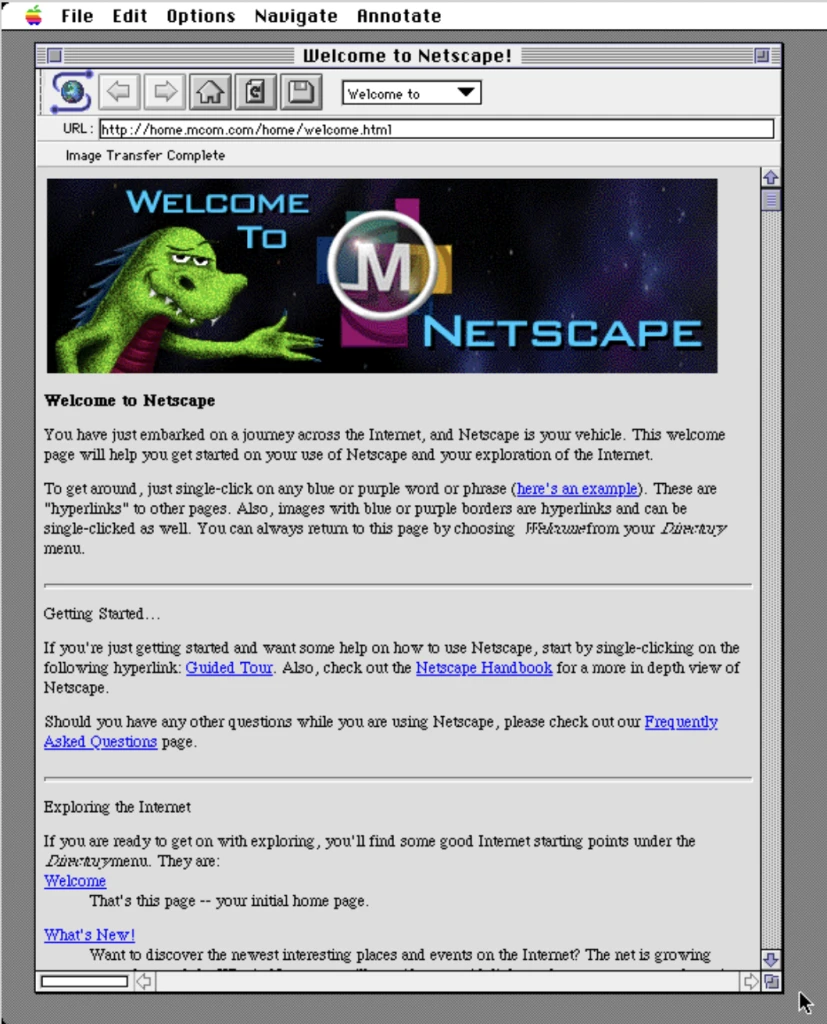

By the end of ’94, Andreessen and Bina would trade the university for Silicon Valley, launch Netscape, and release a new browser called Navigator. After a tussle with NSCA over the name, the browser’s internal code name—and eventual mascot—was the “Mosaic killer,” or Mozilla. (The name lives on: In February 1998, a year before its acquisition by AOL, Netscape released the source code for the browser and created the Mozilla Organization to coordinate future development; in 2003 the Mozilla Foundation was established to continue independent work on a new browser, called Firefox.)

Netscape Navigator, free and wildly popular, easily slayed Mosaic, bringing millions more Windows and Mac users onto the Web over the course of 1995. And it would set Netscape up for an IPO that August, then a highly unusual move for a company that had no profits. The startup ended the day worth $2.7 billion, launching the browser wars and a gold rush that, despite one dot-com bubble, hasn’t really stopped.

But back in ’94, the salesmen and oilmen and land-grabbers and developers had barely arrived. In the calm before the storm, the Web was still weird, unruly, unpredictable, and fascinating to look at and get lost in. People around the world weren’t just writing and illustrating these pages, they were coding and designing them. For the most part, the design was non-design. With a few eye-popping exceptions, formatting and layout choices were simple, haphazard, personal, and—in contrast to most of today’s web—irrepressibly charming. There were no table layouts yet; cascading style sheets, though first proposed in October 1994 by Norwegian programmer Håkon Wium Lie, wouldn’t arrive until December 1996.

“The appearance of websites was mainly influenced by the technological possibilities of the time,” says Petr Kovář, founder of the Web Design Museum, whose exhibited Web pages begin in 1991, when Berners-Lee put up the first one. “The Internet connection was very slow at that time and the websites therefore contained a minimum of graphical elements, with the emphasis being mainly on textual information. The typography was limited to the basic font sets that the user had installed on [their] computer and mostly a footer font prevailed. The navigational structure was generally simple and the user progressed linearly from one page to the next.”

Of course, at 14.4 kbps, it could take a minute to download a large image; in September, a new kind of modem would double connection speeds, from 14 kbps to a blazing 28.8 kbps. Until the arrival of 56K modems in the late ‘90s and commoditized broadband around the turn of the century, bandwidth was a frequent issue for early Web surfers. In Mark Butler’s How to Use the Internet, one of a number of guides published in ’94, the single chapter about the Web notes that “you may have to wait a long time to receive a document, or, in some cases, you may not even be able to make a connection.”

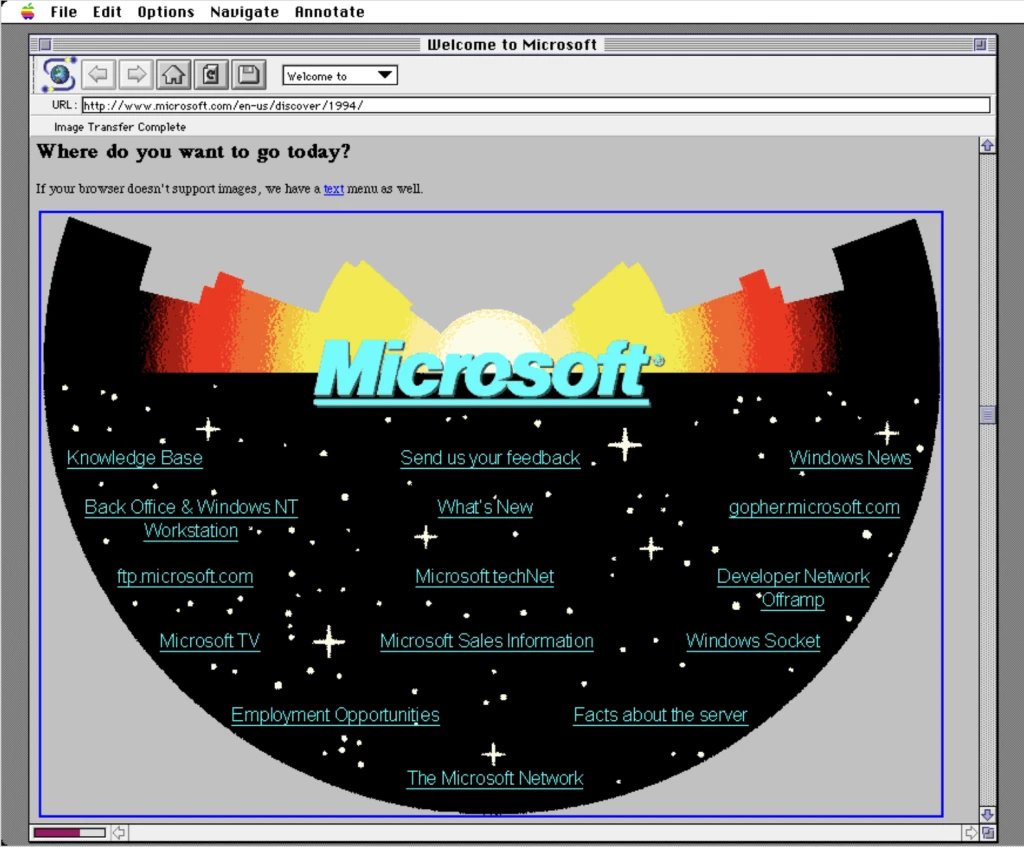

The fickleness and sluggish speeds and the modem’s loud dial-up whistles: These lost markers of the early Internet suggest a time when our information superhighway was little more than a humble country road. The highways and megalopolises would come later, courtesy of some of the world’s biggest corporations and increasingly peopled by bots, but in 1994 the internet was still intimate, made by and for individuals. Even such corporate like Microsoft’s were managed by a single person. Soon, many people would add “under construction” signs to their Web pages, like a friendly request to pardon our dust. It was a reminder that someone was working on it—another indication of the craft and care that was going into this never-ending quilt of knowledge.

Signs like those can be hard to find on today’s internet. As the web slides into a new period of decline—warped as it’s become around platforms and profiteers and propagandists, polluted by the scrapings and regurgitations of bots and spam and slop and slime—there’s a growing push to return to some of the more democratic principles of the old days. With the future in mind, I recently went poking around for some parts of the old web that launched in 1994, and still define it today. Beyond sheer nostalgia, there might be something useful about browsing the Web’s baby photos, back when it was still the Next Big Thing. What screenshots we can still get are like windows into an alternate world. Look in and think about how and why this web grew the way it did, and what could have been. Or try to imagine what life was like when the web wasn’t worldwide yet, and no one knew what it really was.

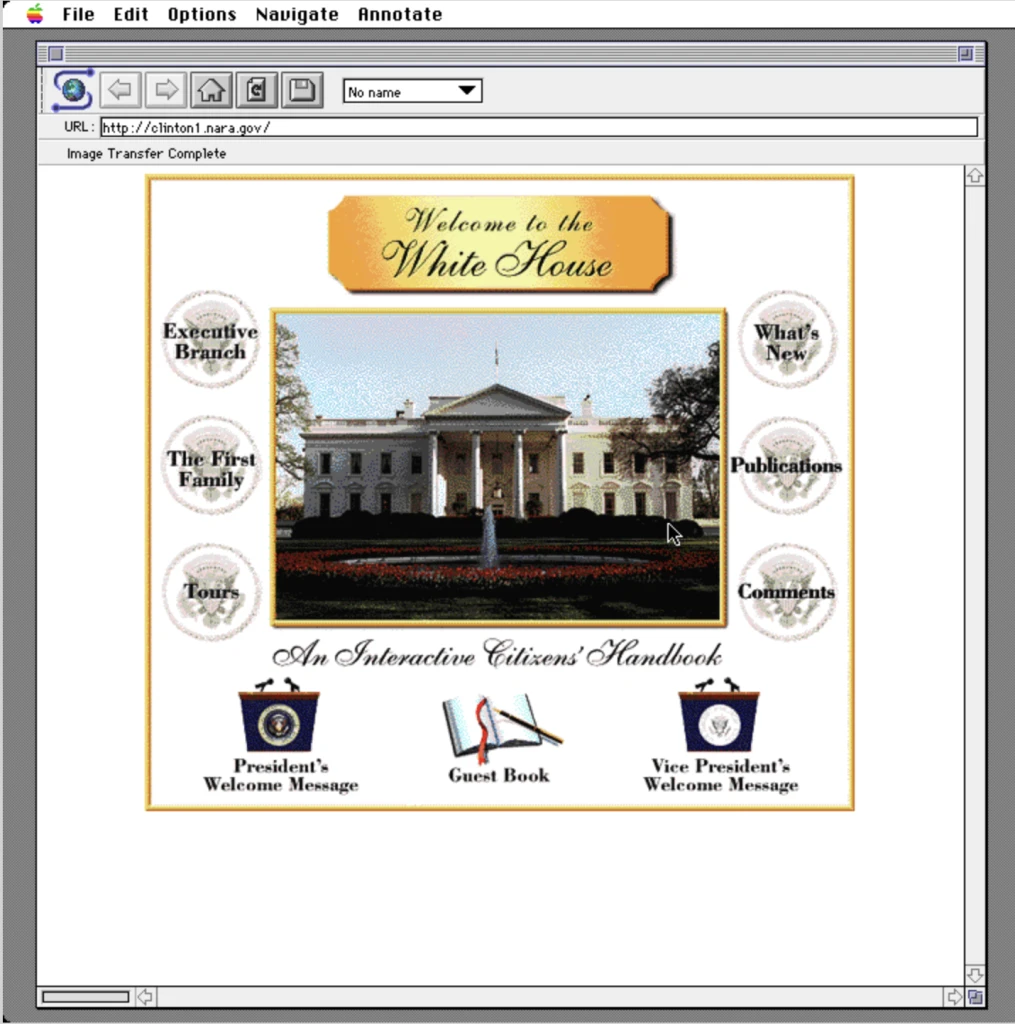

WHITEHOUSE.GOV

The Clinton administration had come to the White House with big plans for the “information superhighway,” but no one had thought much about setting up a Web page. Then, in November 1993, the White House purchased a costly T1 line—a dedicated connection to the internet via DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—and Jack Fox, the White House IT director, wanted to know what they were going to do with it. He posed the question one morning at a meeting of aides and executives, including Anthony Rutkowski, a representative from Sprint, which had the T1 contract. There was a long pause.

Finally, Rutkowski—inspired by his family’s recent visit to the White House—put an idea on the whiteboard for a basic “virtual tour.” Everyone liked it. Except, it turned out, his bosses at Sprint, who saw no reason why the telecom giant should start building websites. Rutkowski got to work on a home workstation. “Images from the guidebooks my father had purchased were scanned, and an initial prototype website was created,” he recalled in a 2020 essay. “My young daughter Kelly contributed to the design, insisting that any White House site had to feature Socks the cat.”

After receiving the green light, the next step was to reach out to a friend: Eric Schmidt, Sun Microsystem’s “ubiquitous, always available” CTO. The future Google chief and frequent White House guest loaned out a couple of Sun’s new quad processor servers, which were then set up in an empty old room in the Executive Office Building. Tony Villasenor at NASA was brought in to help with programming. But Rutkowki and his team struggled with two basic challenges.

First, finding photos and audio for Socks the cat, which users would be able to play in a popup window. Second, figuring out how to link to other agencies, almost none of which had websites. A prototype White House website index page was assembled and printed in color for someone to hand out—allegedly by POTUS—to embarrass agency heads without a Web presence into getting to work. “Those who didn’t have sites appeared in a dull gray on the index,” Rutkowski recalled. “It took several months to get even a few of them online.”

WhiteHouse.gov’s design, with its skeuomorphic gestures, occasional cursive font, clip art, .wav files, and cats, is very early Geocities, although it preceded that community of websites by a year. In addition to welcome messages from the president and vice president, there were pages dedicated to “Publications” and the First Family, and even a sampling of the vice president’s “large personal collection of cartoons characterizing his public life.” (One page was left unfinished: “Some text goes here. Blah blah blah blah,” someone wrote.) When the site launched on October 20, 1994, it was one of the first government websites of its kind anywhere. “The effects,” Rutkowski remembered, “were exponential, immediate, and global.”

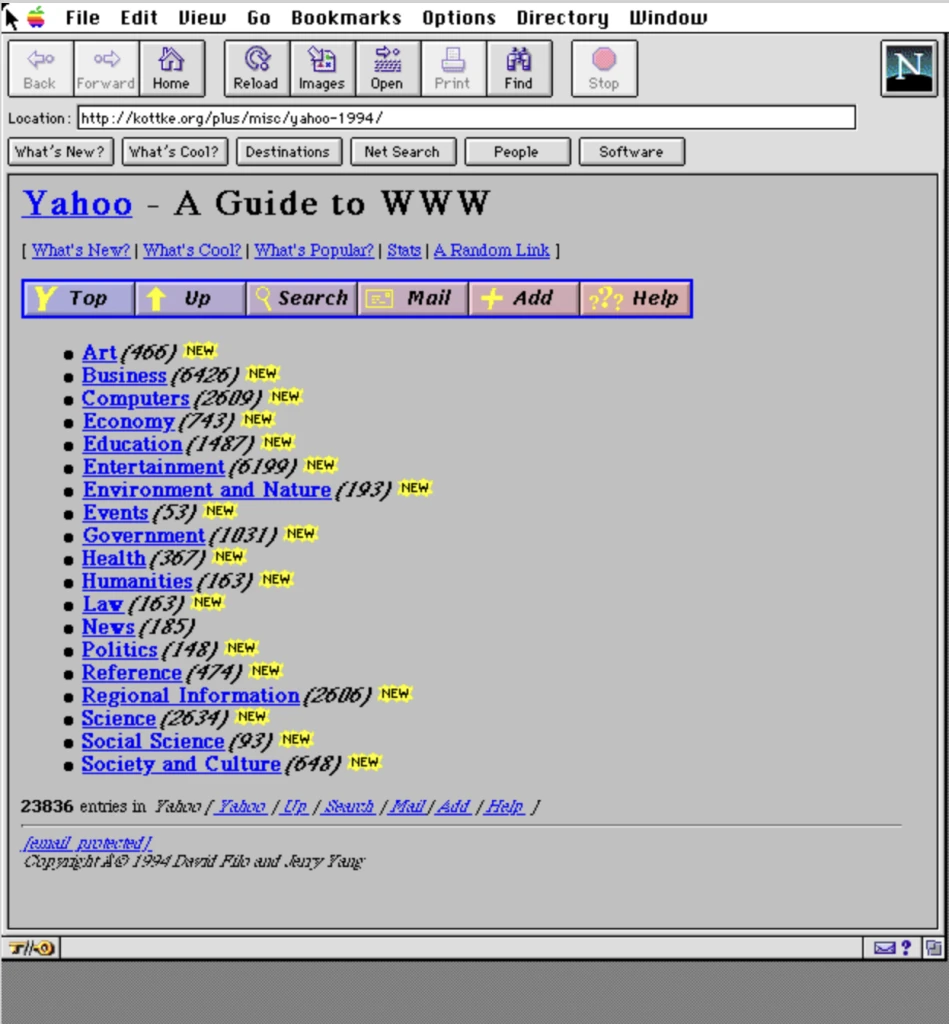

YAHOO!

Searching and finding things on the ballooning Web was already a serious challenge in 1994. “In the long term,” Berners-Lee wrote in a 1992 essay on the problem, “when there is a really large mass of data out there, with deep interconnections, then there is some really exciting work to be done on automatic algorithms to make multi-level searches.” That January, one promising early approach appeared at “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web,” an online directory of favorite websites launched by David Filo and Jerry Yang, electrical engineering PhD students at Stanford. Inspired by slang that Filo heard in his native Louisiana for a “rude, unsophisticated, uncouth” person, in March they renamed it “Yahoo!” and created the backronym, “Yet Another Hierarchically Officious Oracle.”

Other big search engines and directories launched in 1994, including Infoseek, WebCrawler, Excite, Lycos, and the World Wide Web Worm. But an eon before Google.com arrived in 1998, Yahoo! became the most popular way to find things online. The URL officially changed in January 1995, and soon the site added a search engine and a news page and an email provider, all of which are still going—which does seem worthy of an exclamation point. (The original home page is long gone, but Jason Kottke has thankfully preserved an original version.)

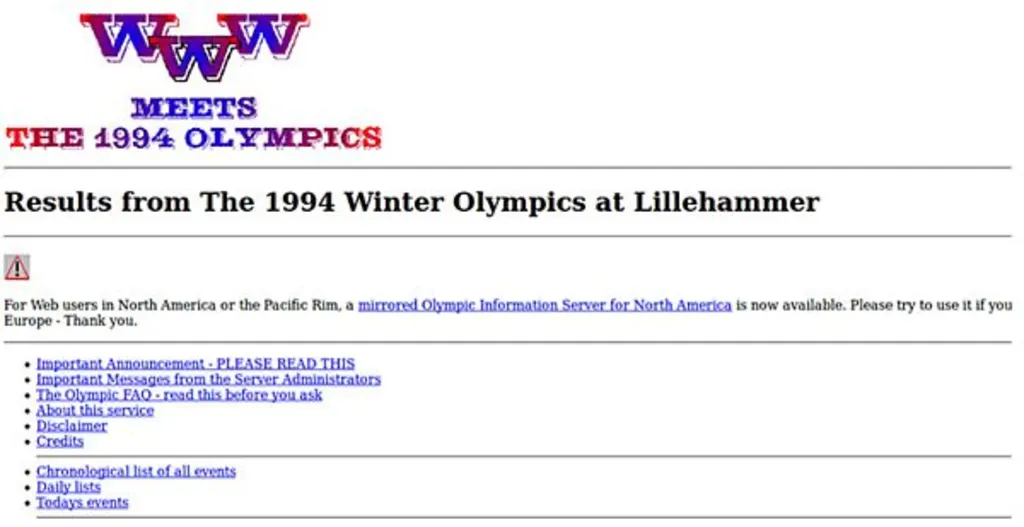

THE OLYMPIC GAMES (AND IBM)

Oslonett was Norway’s first Internet company; and in 1993, after offering services like email and Usenet, it was preparing to offer its users access to the World Wide Web. The upcoming Winter Olympics in Lillehammer offered an ideal opportunity. The company signed a deal with Sun Microsystems, one of the game’s sponsors, and with Norwegian TV, to put up a live-results service along with pictures of the events. By the second week of the Games, the Oslonett server and a mirror at Sun in California had been accessed 1.3 million times by users from between 20,000 and 30,000 computers in 42 countries. “That demonstrated how a site can get overloaded,” remembered Berners-Lee.

Oslonett got the attention it wanted, but other corporate sponsors were unamused. IBM, a main sponsor of the Olympics, didn’t like all the free publicity that rival company Sun was getting. “They tried to stop it,” Steinar Kjærnsrød, one of Oslonett’s cofounders, told Robert Cailliau and James Gillies, “but it was completely legal, we’d made sure it was legal!” Executives at IBM were still stewing over Sun’s coup when they rolled out the company’s first Web page that May. Sun pushed out its own first webpage soon after.

MICROSOFT

One of the main reasons Microsoft started a website in 1994 was customer support. At the time, the company managed support forums for customers on CompuServe, one of the earliest major Internet dial-up service providers. “We had started to build up a community there; people would answer questions for each other,” Mark Ingalls, a Microsoft engineer in 1994 who would become the site’s first webmaster, recalled in a company history. He was also the only website employee at that time, other than his boss.

Included on the splashy image map on the front page were links to such artifacts as Microsoft TV, Microsoft techNet, Windows Socket, and gopher.microsoft.com, the company’s pre-Web Internet presence. (MSNBC, its internet-savvy news venture, wouldn’t launch until 1996.) There was even a page dedicated to “Facts about the server,” which included a photograph of Ingalls standing next to a single machine.

That year, UX consultant Jakob Nielsen reported that all users surveyed “liked” this page in particular. “They felt that it was nice to know that they were communicating with a service supported by an actual person and not a faceless entity,” he wrote. “The users also liked being able to read the technical specifications for Microsoft’s server, again from the perspective that the information was not just coming in over the wire, but was coming from somewhere.”

TIME WARNER’S PATHFINDER

Time Warner’s Pathfinder was one of the first web portals, created as an all-encompassing entry point to “multimedia” content (photos! graphics!) from across the media behemoth’s titles, including Time, People, Fortune, and Vibe. The site opened on October 24, 1994, with a small content team that included Walter Isaacson and an eye-catching design. (For the time, it was a lot. According to a survey by Nielsen, “all users found the Time Warner page too complex.”)

Now that the Internet could look something like a magazine, the site was meant to inaugurate a new era of digital publishing. “We have every base covered now,” Isaacson, then editor of new media at Time Inc., told the New York Times. “We are going to have the best and the most ways to distribute our journalistic content to consumers, in any form they want—TV, on-line, CD-ROM, cable and, of course, our core business, print.” Still, the paper noted “a looming question”: Who’s making money putting journalism online for free?

“No one is making money,” said Richard M. Smith, editor-in-chief and president of Newsweek, who also was in charge of the new-media committee for the Magazine Publishers of America. “And no one should expect that anyone should make money at this early stage. It’s research and development.”

By the time Pathfinder closed in April 1999, it had cost Time Inc. somewhere between $100 and $120 million. Ironically, it was Pathfinder’s failure that may have led to Time Warner’s eventual pursuit of a merger with AOL, a $360 billion tie-up that sought to generate “synergy” between the old media empire and the one-time digital giant. But then, with the rise of broadband internet, the whole enterprise came crashing down: AOL was eventually spun off from Time Warner in 2009, acquired by Verizon in 2015 for $4.4 billion, then sold, along with Yahoo!, to private equity firm Apollo Global Management for $5 billion. These days, AOL is part of Yahoo!.

GLOBAL NETWORK NAVIGATOR

If you wanted to get online in 1994, your paper bible was Ed Kroll’s Whole Internet User’s Guide and Catalog, a 600-plus-page tome of how-tos, explainers, and histories. When Berners-Lee first proofread it, in Chicago in the spring of ‘93, the Web occupied just one chapter. But Tim O’Reilly, the book’s 40-year-old publisher, had big plans for the new frontier. He’d just started a four-person “skunkworks” team to begin planning for a new website, a portal for Kroll’s guide and the rest of the publisher’s content.

Global Network Navigator (GNN) was officially launched in August 1993, under the leadership of Dale Dougherty and Lisa Gansky, as “a free Internet-based information center that will initially be available as a quarterly,” consisting of “a regular news service, an online magazine, The Whole Internet Interactive Catalog, and a global marketplace containing information about products and services.”

The online “magazine” would be free and wholly supported by advertising. By June 1995, GNN had more than 400,000 regular viewers, with 180,000 subscribers to its mailing list; advertisers such as Mastercard and Zima paid as much as $11,000 a week. Things went downhill after AOL bought GNN from O’Reilly & Associates in 1995 for $11 million in stock and cash, and reintroduced it as an internet service provider. By the time AOL finally fired GNN’s staff and folded it into its own ISP in late 1996, GNN had become the fifth-largest ISP in the U.S., with 200,000 subscribers.

Wired’s home on the Web, HotWired, launched on October 7, 1994, with a colorful, irreverent look that would help set the bar for early web design. And as part of its business plan, the site would depend upon a corporate sponsorship model, with a new kind of interactive advertising. Later, the site would pioneer real-time web analytics and behavioral targeting, but bosses at HotWired started with a 468-by-60-pixel banner at the top of the main page. Fourteen advertisers had signed on for the launch, including MCI, Club Med, the now-defunct malt beverage Zima, and Volvo. Somewhere between six and 12 of the billboard-like ads appeared simultaneously that day, but it was AT&T’s that would come to be known as “the world’s first banner ad.”

At the time, the telecom giant had a popular television campaign featuring the tagline, “You will,” showcasing the future that AT&T was working to bring to the masses. “Have you borrowed a book from thousands of miles away? . . . Have you ever watched the movie you wanted to, the minute you wanted to?” Tom Selleck’s voice asked in the commercials. “Have you ever clicked your mouse right here?” the candy-colored banner ad asked. “You will.”

The young designers of the campaign revered the still-uncommercialized digital frontier, even if they also understood that keeping information free would require advertising. (AT&T paid a reported $20,000 to $30,000 for the spot.) “We came with the attitude that this was a sacred ground,” Joe McCambley, who worked on the ad, told Fast Company’s Rebecca Greenfield in 2014. “The rest of advertising had been ruined and dammit, we weren’t going to let that happen this time.”

Clicking on the banner, which didn’t even include the AT&T logo, led to a separate page with three links. The first led to a map of the United States labeled with clickable links to art museums and galleries that had online presences, including digital-only galleries. The second was a directory of AT&T websites, and the last led to a survey asking visitors about the ad. The idea was to help demystify this vast new Web, and make it look cool.

“We really were trying to make sure the internet had beauty,” Craig Kanarick, a designer who worked on the ad, told me. “After all, nobody really knew if users would click on the banners at all and leave their experience at hotwired.com or just scroll past them and ignore them. We just wanted to make sure that if they did click, they didn’t feel like they wasted their time.”

People clicked. By some accounts, after the initial excitement, the click-through rate settled at around 44%, which as a percentage is an astonishing figure. Of course, there were only about 14 million people online at that point—and only tens of thousands of people were reading HotWired. By comparison, today, in the era of ad blockers, most banner ads have a click-through rate of .08%.

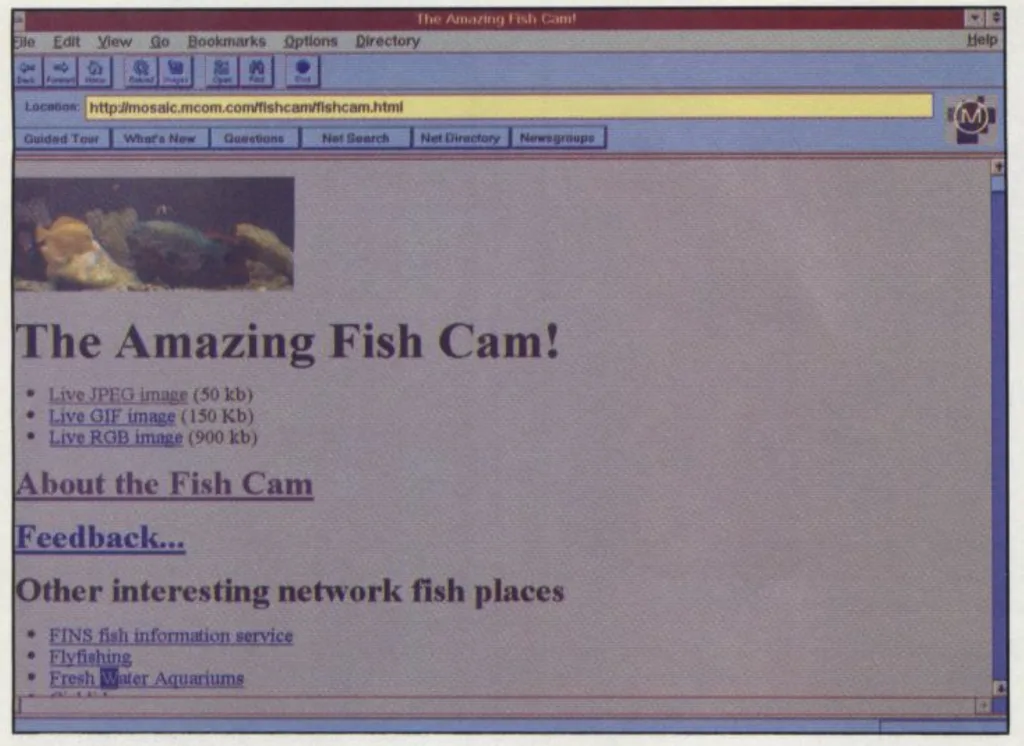

THE FIRST WEBCAMS

In July 1994, Jeff Schwartz and Dan Wong launched FogCam! (fogcam.org) at San Francisco State University to track changes in the local weather. It remains the oldest still-operating webcam in the world. (The first webcam, the Trojan room coffee pot cam at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., first came online in 1991 but was retired in 2001.) Later that summer, 24-year-old Netscape engineer named Lou Montulli debuted The Amazing FishCam (fishcam.com), which provided a continuous web feed of an aquarium in the Netscape headquarters. FishCam is said to be the second live camera on the web and after a few stints offline, it’s still running, though now pointed out a driveway window. “In its audacious uselessness—and that of thousands of ego trips like it—lie the seeds of the Internet revolution,” The Economist wrote at its birth. Not to diminish Montulli’s other contributions to the Web, including the ‘BLINK’ tag, HTTP proxying, and, with the release of Netscape’s browser in October 1994, the cookie.

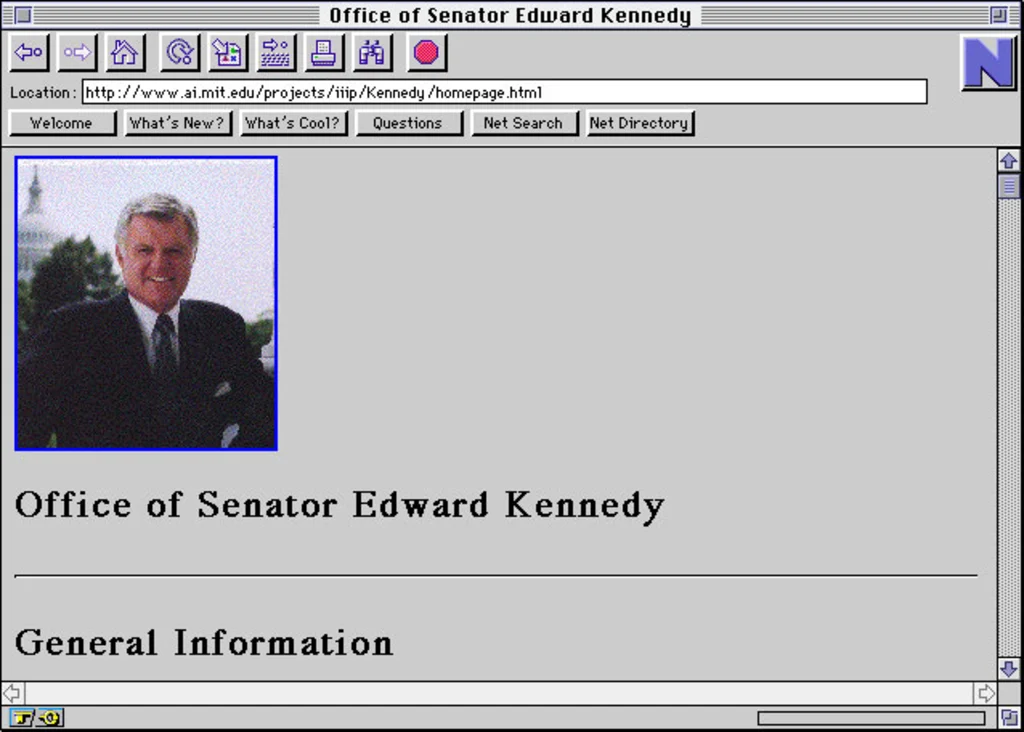

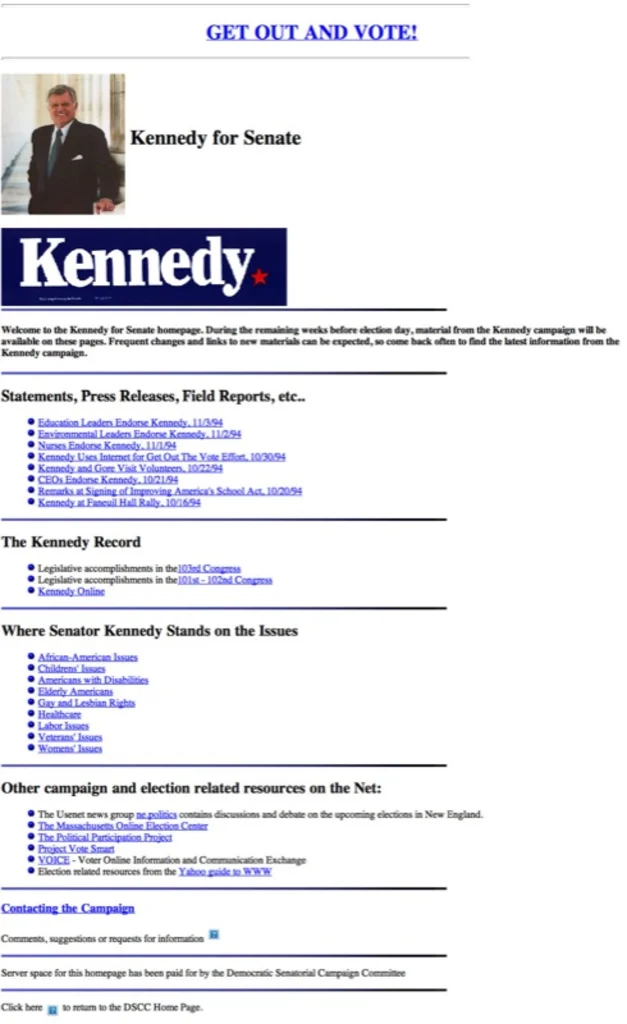

THE FIRST CONGRESSIONAL WEBSITE

In 1993, Chris Casey was working as Senator Ted Kennedy’s systems administrator, even if he had no real technical experience beyond Kennedy’s office network of Macs. “Any Senate office that was attempting to explore and utilize this recently-heard-about ‘Internet’ thing generally had to find their own way, without any institutional help from the famously slow-to-change Senate,” Casey recalled in 2009.

After well-received efforts by the office to post the Senator’s press releases and solicit public comment on BBS, Casey reached out to the White House staff who were then working on WhiteHouse.gov, and was put in touch with two MIT students who were helping that effort, John Mallery and Eric Loeb. They worked with Casey to launch Kennedy’s website in the spring of ‘94—the first for any member of Congress—on a server at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Lab (senate.gov provided only FTP and Gopher services at the time). Kennedy and his team also chose to include his brand-new email address, and braced themselves for a new kind of challenge that would eventually come to every Congressional office: sorting through and responding to torrents of constituents’ emails.

Kennedy’s Web presence wouldn’t stop there. In 1994, he faced a serious challenge for his seat by Republican Mitt Romney. Some polls even predicted his defeat. That fall, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC) contracted with Issue Dynamics Inc. to help develop a basic website for each of their Senate candidates. Considering Kennedy’s online efforts, DSCC gave his campaign staff direct access to manage their campaign site and to make it their own. Launched only a few weeks prior to Election Day, the site contained issue papers, press releases, and endorsements. Fundraising “was still little more than a geeky politico’s daydream,” remembers Casey. “I was particularly proud of my use of the new ‘BLINK’ tag on the Election Day GET OUT AND VOTE! link at the top of the page.”

Meanwhile, he says, Romney was nowhere to be found online and was chided in the media for it. Kennedy ended up winning handily, and a Newsweek article about digital politics later dubbed him CyberTed: “It helped counter his image as an out-of-touch baron who reeked of Old Politics. And it impressed the world of computer jocks, thousands of whom work in the important Boston branch of the industry.” It wasn’t until the year 2000 that all Senators had their own website.

Casey notes that Kennedy’s online experience did more than just generate good press; it helped inform his positions on important digital issues which many of his less-savvy colleagues were ill-equipped to understand. One early example came when the Senate voted in 1995 on the Communications Decency Act, a far-overreaching effort to censor adult content on the Internet. The bill passed by a vote of 84-16, despite Kennedy’s best efforts. Two years later the Supreme Court overturned the act as unconstitutional by a unanimous vote.

THE FIRST ENCRYPTED ONLINE TRANSACTION

On August 11, 1994, Phil Brandenberger logged onto a new website called NetMarket and paid $12.48, plus shipping costs, for the Sting CD, Ten Summoner’s Tales. It was the first online transaction protected by encryption technology. “Even if the NSA was listening in, they couldn’t get his credit card number,” Dan Kohn, the 21-year-old entrepreneur behind NetMarket, told the New York Times.

The idea came to Kohn while studying abroad at the London School of Economics, where he was able to remotely connect to his Swarthmore computer to check his email and read updates on Usenet. “As I was using it every day,” he told Vice’s Noisey in 2019, “thinking about it, and also just reading a lot about business ideas and startups, it just sort of dawned on me: Why aren’t people doing commerce on this network?”

Not everyone agrees on this milestone. The Internet Shopping Network, which began selling computer equipment online in 1994, beat NetMarket by about a month, the site’s former CEO told CNet in 2004. But the Sting CD signaled the opening of a new frontier, and hinted at other world-shaking platforms to come.

A month later, a young ex-hedge funder would register Relentless.com; the next year, he would change its name to Amazon.com. Netscape Navigator 1.0, released that December, pioneered the SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) Protocol, which established an encrypted link between browser and server. Bitcoin wouldn’t show up for at least another decade, but Phil Zimmermann, the inventor of PGP encryption, saw a glimmer of something in that first purchase. “I think it’s an important step in pioneering this work, but later on we’ll probably see more exciting things in the way of digital cash,” he told the Times, “some combination of cryptographic protocols that behave the way real dollars behave but are untraceable.”

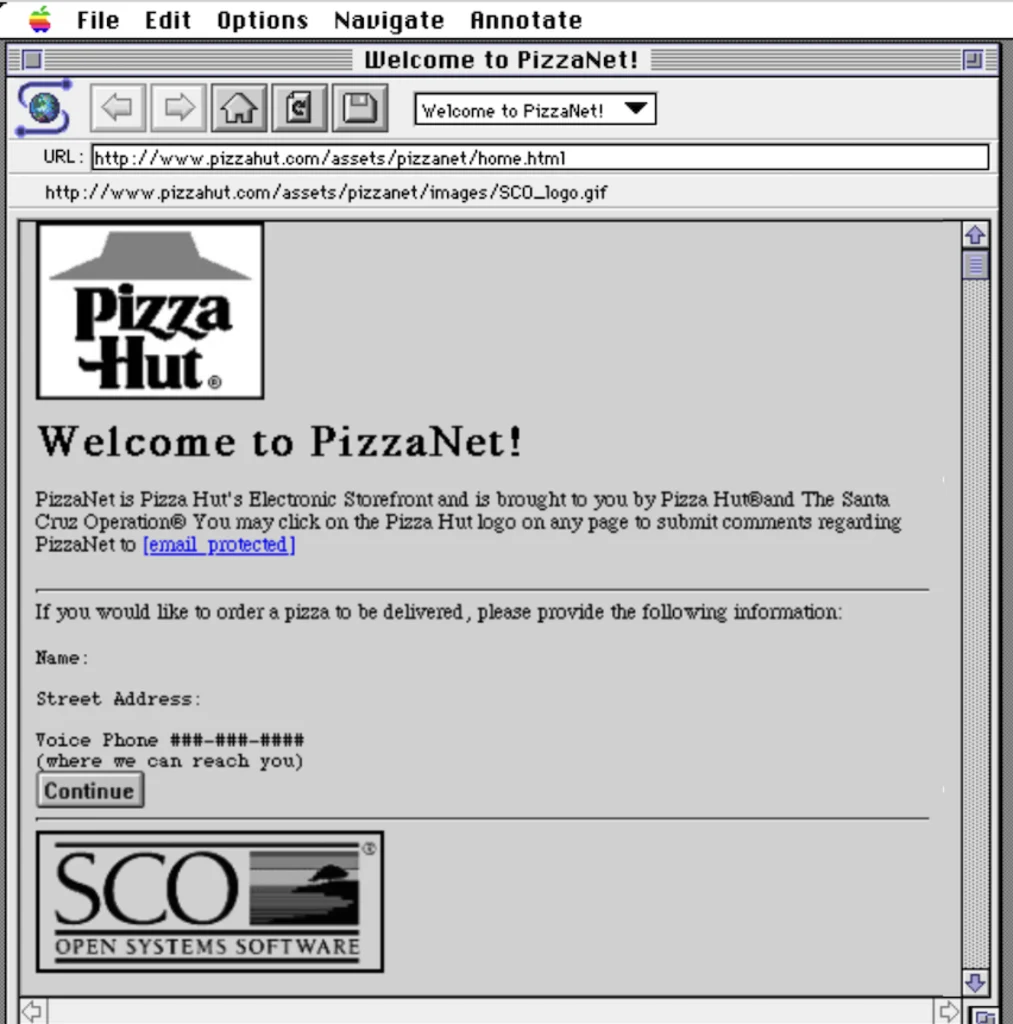

PIZZANET (AND THE FIRST LIVESTREAMED CONCERTS)

On August 22, 1994, Pizza Hut made history with PizzaNet, which allowed people to order pizza via the Web for the first time. Well, people in Santa Cruz, California. “In a revolutionary spin on business use of the Information Superhighway,” a press release declared, the pilot program let customers dispatch their information and pizza order “via the Internet back to Wichita,” where it is “then relayed via modem and conventional phone lines to the SCO Open Server system at the customer’s nearest Pizza Hut restaurant. The local restaurant can then telephone first-time users to verify orders. All money changes hand at the point of delivery.”

The first order was pepperoni with mushrooms and extra cheese. News of the site—if not the site itself—sent shares of Santa Cruz-based software vendor SCO soaring. Even Silicon Graphics, the tech hardware company, saw its stock rise nearly 10% in one hour when a KCBS radio reporter mistakenly called them “the Internet pizza company.”

Later that week, a few employees at SCO made more internet history, as Deth Specula, the company band, performed in one of the first live rock concerts livestreamed over the Web. (They kicked off with their parody of the Grand Funk Railroad song “We’re An American Band,” called “Internet Band.”) The concert used the Multicast Backbone, or M-Bone, an early streaming technology by Xerox PARC that was also used that year to simulcast some of the first Web conference in Geneva, and, two months after Deth Specula’s show, the first “major” livestreamed concert: a tour stop in Dallas by the Rolling Stones.

WELLS FARGO

When Wells Fargo launched its first website on December 12, 1994, becoming one of the first banks with a web presence, banking online was still a fantasy. Instead, the page functioned mostly as a marketing tool, offering access to brochures and banking products, links to history and trivia and high-resolution pictures of Wells Fargo’s iconic stagecoaches—a nod to its origins on another frontier, providing “express” delivery and banking services to California at a time when it was growing rapidly due to the Gold Rush.

“Unfortunately,” notes a corporate history, “with dial-up-internet access the norm, the colorful stagecoach pictures downloaded one line at a time and took several minutes to load the whole site. Customers used the built-in feedback button to submit their frustration and disappointment with the slow speed. . . . Another common question asked by customers was: When can I check my account balance on the website?” The following year, a small task force built new security features and installed new servers to handle the volume of online activity. In May 1995, Wells Fargo became the first major bank to allow customers to access their accounts via the Web.

In early 1994, as the bank worked on its first Web page, Wells Fargo executives turned to CommerceNet, an early online business directory, to try to establish a Web presence even sooner. They started by sending CD-ROMs full of photos. “They’d say, ‘Here’s like a splash screen we’d like you to put up for our first web page,’” recalled Kevin Hughes, who was helping CommerceNet with its website at the time, and who spoke to the Computer History Museum in 2010. “It was just a photo of two guys on a stagecoach saying, ‘Under construction. Be back soon.’ That was Wells Fargo’s first web presence.”

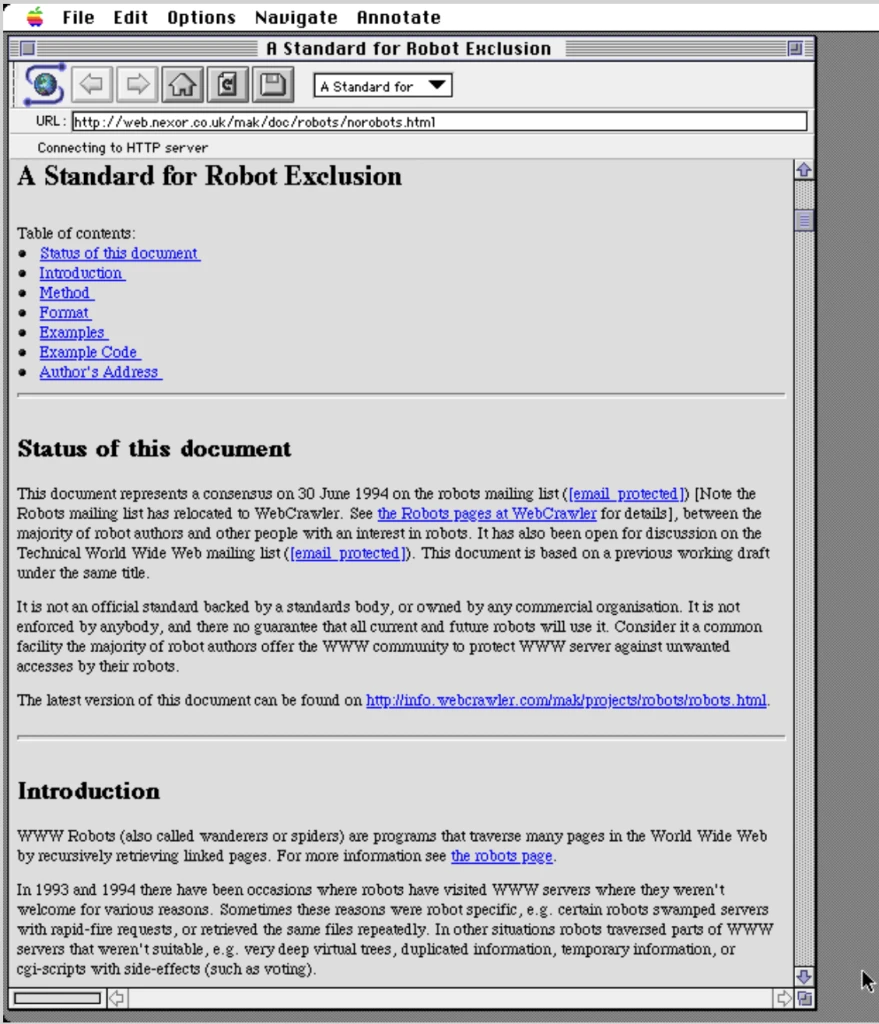

ROBOTS.TXT

On July 3, 1994, Dutch software developer Martijn Koster emailed the W3C www-talk mailing list, which included Berners-Lee and all the Web’s main engineers, with a modest proposal. The rules of what they called the Robots Exclusion Protocol—developed along with a group of other web administrators and developers—would be stipulated in a robots.txt file in a website’s index folder, and would define what parts of a website robots are permitted to crawl. Koster couldn’t have known that, for decades, this little file would keep the internet from utter chaos.

Koster didn’t hate robots, he insisted, but for him and other server administrators, they often meant surprise cost surges and technical issues. “Robots are one of the few aspects of the web that cause operational problems and cause people grief,” he wrote in that initial email. “At the same time, they do provide useful services.” At the time, crawlers were used to index information to improve search engine results. The standard has become a central tenet and feature of the global network, underpinning the deal that made the web flourish: if you build it—and web crawlers index it—they will come.

But like a lot of the web, the regime operates on the honor system, and the bots don’t always abide by these rules. And these days, the crawlers aren’t just helping human bosses eager to improve web searches; they’re helping companies grab the data their machine-learning models desperately need to generate text, imagery, and more. “AI companies have leached value from writers in order to spam Internet readers,” Medium’s CEO Tony Stubblebine said last fall when he announced the blogging platform would attempt to block AI crawlers. Lately, some big platforms and AI companies, so eager for training data, aren’t just ignoring robots.txt: some small websites are getting scraped so hard, they’re getting knocked offline.

Google, which crawls the web like no one else, helped make the Robots Exclusion Protocol an official formalized standard a few years ago. (For robots.txt’s 20th anniversary, the company also posted a joke file at /killer-robots.txt, instructing a future T-1000 and T-800 to not kill founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin.) Lately, Google has pushed to deemphasize robots.txt because too many people now ignore it. It could be a metaphor for the web so far, and a cautionary tale for its future: A group of people built a simple protocol to keep the web open and fair and usable, and to keep the data miners and the robots at bay for as long as they could.