“There are only two kinds of people in the world,” I tell my friend as we hike a dusty trail above the Flathead Valley in Montana last summer. “Me, and everybody else. That’s what nobody gets.” I try to explain how much work I put into interacting with other people—with anyone. I tell her how much energy goes into processing even the most minor conversation. I’m not usually this frank about what goes on inside my head; better that people don’t know.

Explaining often feels pointless. I always seem to fall short when relating the stress of social interactions. Friends and family attribute this to introversion or social anxiety, or some other more familiar trait. They want to be able to relate to my experience; but early last year, I learned why they can’t. At the age of 38, I learned that I’m autistic.

It turns out that autism contributes to some of my greatest strengths: hyperfocus, pattern recognition, written communication, systems thinking. But autism is also the source of my greatest frustrations when interacting with others: verbal-processing delays, overstimulation, recognizing emotion and social cues. I don’t experience autism as an issue when left to my own devices.

But I’m a wife and a mom. And, up until recently, I was also a facilitator, coach, community builder, and employer. My weeks were full of meetings and coaching sessions; I was constantly surrounded by “everybody else.” And no one knew how much I was struggling because I’m so practiced at being the charismatic, personable person they expect me to be.

My friend asks, “How did you end up building a business so unsuitable for you?” Denial, I tell her. I’d thought maybe my difficulty was a skills gap, or a personality quirk I could learn how to manage better; I just need to learn more networking and management skills, I thought. I’d always believed I could rise to whatever challenge I valued overcoming. Why should the social components of my work life be any different?

Trying to overcome my challenges, I learned about psychological safety, setting expectations, and holding space. I made it my business to understand what to do when big feelings were present on a call with a client. I collected phrases and facial expressions on mental notecards and memorized scripts that were useful in response. I was fully convinced that I could conquer my social and emotional “deficits.” I didn’t have to let this “impairment” define me.

Autistic masking or camouflaging is the work—sometimes conscious, sometimes unconscious—that autistic people do to fit into a neurotypical world. We suppress natural responses, even parts of our identity, to appear “normal” and make others comfortable. While research on this behavior is only just starting to emerge, one 2017 paper described masking as “constant monitoring” of social interactions, which led to high levels of stress and anxiety. A 2019 study documented a significantly higher presence of depression among autistic people who mask versus neurotypical people. Further consistent camouflaging can lead to losing your sense of identity, experiencing low self-esteem, and just generally feeling like a fake. Masking is also associated with burnout, a consequence I’m intimately familiar with.

The more I learned about masking, the more it reminded me of emotional labor. In the early ’80s, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild described emotional labor as the result of “feeling rules” becoming encoded into a job description. It’s “service with a smile” and “the customer is always right.” It’s also the charge to treat customers and coworkers like family or bring “your whole self to work.” Because emotional labor is often invisible, under-compensated, and unrelenting; it creates a significant risk of burnout and self-alienation.

Everyone does some form of emotional work in their daily interactions. Many people—especially women and people from marginalized groups—perform emotional labor in their workplace. Masking at work is a particular form of emotional labor. While autistic people are often stereotyped as lacking empathy and not dealing well with emotions, many autistic people are masters of emotional labor.

Back on the dusty trail, I owned up to how masking and emotional labor had left me broken: self-alienation, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization. I collapsed into tears regularly—not normal for me. I had an overwhelming need to curl up in a ball multiple times per day.

I knew something needed to change. By year’s end, I had untangled myself from the work I’d spent a decade building—a job that I loved but also that made me sick. I’ve started to unravel my internalized ableism and the drive to overcome my real limits. Today, I’m figuring out what my work can look like, given the strengths and challenges of autism.

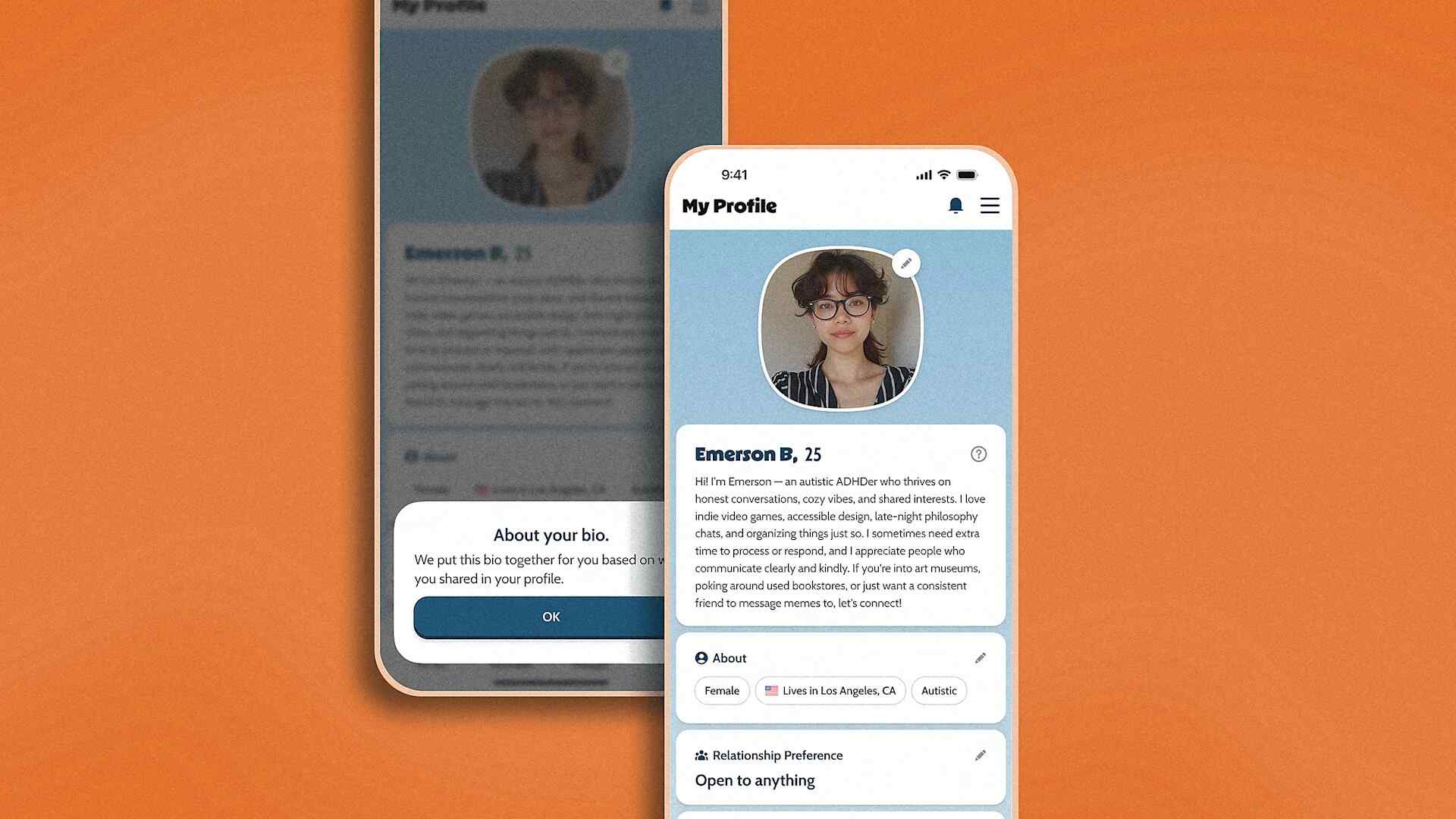

The most significant change I’ve made to how I work is to be upfront about my needs. I’m willing to say, “I don’t know what you mean,” when someone speaks figuratively. I’m more apt to request to work asynchronously rather than on Zoom meetings. I’m much more likely to just straight up say, “I’m autistic, and here’s what you can expect. . . .” Being frank about my needs allows me to let my guard down a little and relax. In turn, I can put the energy I would have spent on anxious self-monitoring toward doing better work.

I’m incredibly privileged. I have ultimate control over my work and several safety nets to fall back on. But I’m left thinking about the autistic people in workplaces where they don’t call the shots.

Researchers note that autistic camouflaging and emotional labor is often used to avoid stigma or discrimination in the workplace. That begs the question, How can the workplace evolve to accommodate autistic people? Should it be our sole responsibility to put others at ease or prove ourselves worthy of a promotion? Or are there ways—like through more opportunities for asynchronous collaboration or more flexible Zoom rules—that leaders can create environments in which autistic people can thrive?

We shouldn’t have to prioritize “everybody else” at the expense of losing ourselves at work. My sincere hope is that all autistic people would have the chance to work in an environment that not only accepts us for who we are, but sees our unique traits as strengths.