- | 8:00 am

It’s time to reframe our thoughts around anxiety. Here’s how to use it productively

A professor of neuroscience says, “To feel good is to know how to feel bad: how to listen to anxiety when it rises and falls, and how to work with and through anxiety.”

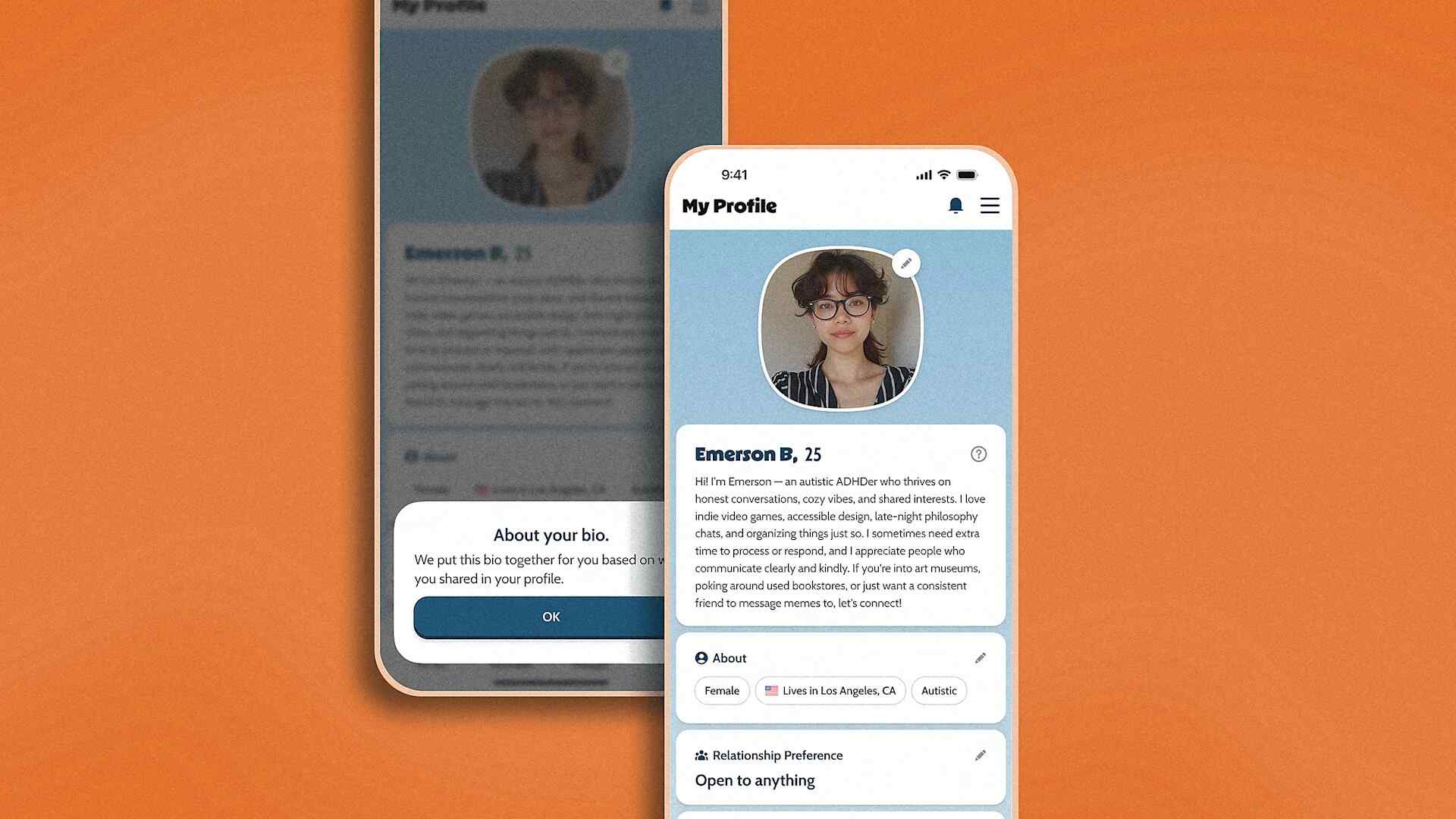

Tracy Dennis-Tiwary is a professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at The City University of New York. She is also the co-founder and CSO of Wise Therapeutics, a digital therapeutics company that creates casual, accessible mobile games designed to improve mental health.

Below, Dennis-Tiwary shares five key insights from her new book, Future Tense: Why Anxiety Is Good for You (Even Though It Feels Bad). Listen to the audio version—read by Dennis-Tiwary herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. OUR FALLACIES ABOUT ANXIETY ENCOURAGE DETRIMENTAL COPING METHODS.

Even before the pandemic, debilitating anxiety was rising with no sign of slowing down—this, despite cutting-edge therapies, excellent self-help books, a wealth of science-based wellness practices, and a panoply of anti-anxiety medications. In short, all of this isn’t working.

Mental health professionals have made a terrible mistake by promulgating two key fallacies about anxiety. First, that anxiety is dangerous and destructive, and that the solution to its pain is preventing and eradicating it. And second, that anxiety is a malfunction of happiness and mental health, which, therefore, needs to be fixed.

These fallacies unintentionally harm us, because they make us anxious about anxiety. We try to avoid and suppress it at all costs—which always makes anxiety worse and blocks our ability to find helpful ways of coping. These fallacies also suppress any curiosity about anxiety, or interest in using anxiety for its true purpose: an evolutionarily propelled advantage for protection, and to energize us to be more creative, socially connected, and persistent.

These false views of anxiety have it entirely backwards. The problem isn’t that we feel too anxious—the problem is that we haven’t mastered how to feel anxious.

2. ANXIETY MOTIVATES US TO HOPE AND PERSIST IN OUR GOALS.

Anxiety feels bad: nervous energy, butterflies in the stomach, pounding heart, worried thoughts, or maybe outright panic. These feelings make us strongly suspect that something is wrong, either with the world or with us.

It turns out that this “bad” feeling is also a triumph of evolution. It emerged along with one of our greatest human attributes: the ability to think about, imagine, and prepare for the future. While fear roots us to the present moment, anxiety makes us mentally time travel to the future. It is that feeling of considering the uncertainty of what lies ahead, and anticipating the possibility of something bad happening, but also understanding that something good could happen. Anxiety helps us imagine the possibilities and care about making the best option a reality. That’s why anxiety is inextricably linked to hope, and it sharpens our focus, helps us persist through obstacles, and motivates creativity, innovation, and social connection.

One key to reaping these benefits is thinking about anxiety differently. In 2013, researchers conducted an experiment in which they tasked socially anxious participants with an impromptu public speech about a contentious topic. They found that those participants who learned to reframe their anxiety as an advantage performed better under pressure, were more confident, and had a cardiovascular response (steadier heart rate and lower blood pressure) that emerges when we’re focused and engaged. This study showed that by simply changing our perception of anxiety from that of a burden to that of a benefit, our bodies follow suit in preparation for the challenges ahead.

3. ANXIETY PRIMES US FOR SOCIAL CONNECTION AND CREATIVITY.

We often assume that anxiety causes stress. Sometimes it does, but new research shows that anxiety often buffers against stress through the biology of social connection and by motivating creativity.

When we’re in the throes of anxiety, levels of the hormone oxytocin (sometimes called the “love hormone”) spike. Oxytocin plays a broad role in social bonding, including romantic relationships, reproduction, childbirth, and caregiving. Whenever activated, oxytocin primes us to connect to others. Research on social buffering shows that connecting with others is one of the best ways to manage all types of distress, including anxiety, on the biological level.

A 2006 study from the University of Wisconsin put participants in a high-anxiety situation: they entered a loud, claustrophobic MRI machine to have their brain scanned while awaiting the unpredictable, but certain, threat of an electrical shock. One third of the group were allowed to hold the hand of a loved one, one third held the hand of a stranger, and the last third were left alone. Researchers found that holding a loved one’s hand while awaiting the shock calmed areas of the brain that are typically activated when the brain is trying to ameliorate stress or soothe anxiety. So, the presence of a loved one calms an anxious brain. Humans evolved to rely on others for solace. We perform “emotional outsourcing” during challenges so that our brains undergo less strain.

Anxiety also inspires us towards creativity. Every performance artist will tell you that if they don’t feel some anxiety, something is wrong. Butterflies before the big performance means you care, or vomiting before your solo shows that you’re in it to win it. But creativity isn’t just the fine arts, and it doesn’t have to be grand. Creativity is in the smallest act of bringing into existence something that did not exist in quite the same way before. All creativity takes persistence, effort, and imagination to see the possibilities in front of us, and anxiety is what lets us focus on those possibilities. Research shows that a period of anxiety increases “creative fluency,” meaning the quantity and quality of ideas, as well as the ability to persist in problem-solving.

4. ANXIETY HAS TO BE UNCOMFORTABLE TO DO ITS JOB.

Anxiety works so well not because it feels great to be anxious. It succeeds because it makes us feel so bad. Anxiety is so unpleasant that we’ll do practically anything to make it go away. Anxiety drives us to do things that protect us and motivate us toward productive goals, which then in turn, by reducing anxiety, signals to us that these actions have succeeded. This cycle is called “negative reinforcement” (stopping the anxious feeling is the reward) and makes anxiety a key step to success. Ultimately, to feel good is to know how to feel bad: how to listen to anxiety when it rises and falls, and how to work with and through anxiety.

You’re only anxious when there’s something to care about. It’s important that we heed what anxiety is telling us. Imagine you’ve been sitting with free-floating anxiety for a couple days. You’ve been trying to ignore it—to keep calm and carry on—but it’s getting to you. So, you decide to tune in to what your anxiety is saying. You go through a mental checklist of what has been bothering you: is it that fight with your husband, a looming work deadline, or worsening acid reflux? Once you identify the source of your anxiety, you have actionable information. If it is the acid reflux, then when you schedule a doctor’s appointment, your anxiety will immediately lessen, because you’re on the right track. When you later see your doctor and are prescribed a solution, the anxiety disappears. Mission accomplished—anxiety has done its job.

However, if you found out that there was actually something seriously wrong with your health, the anxiety would return, and motivate whatever additional steps are necessary to deal with the illness. Without anxiety, you might have lost the chance to survive and thrive.

5. ANXIETY AND ANXIETY DISORDERS ARE NOT THE SAME.

Anxiety is a normal, healthy emotion that people commonly experience. It’s felt along a spectrum, from barely perceptible to overwhelming. But extreme levels of anxiety aren’t enough to diagnose an anxiety disorder. Anxiety disorders are only diagnosed when our ways of coping with intense and enduring anxiety (whether with worries, avoidance, withdrawal, or obsessiveness) are out of proportion and disrupt our ability to function at work, in our personal lives, or physically. The problem in modern society isn’t the experience of anxiety—it’s that how we cope with it can lead to a debilitating anxiety disorder. Treating all anxiety as a disease hinders us from finding ways to manage and use anxiety to our advantage, and from benefiting from treatments when we do need extra support.

Imagine the experience of Kabir, who showed signs of intense anxiety at age 15. At first, he only feared speaking in class. Days ahead of a presentation, he worried constantly, didn’t sleep, and refused to eat. He made himself sick with worry. Over time, he missed more and more school days, and his grades suffered. Soon, this extreme and constant worry arose in response to non-school situations—like when he was invited to parties or had swim meets. Within months, he stopped doing either and broke off the few friendships he had. By the end of the year, he was having full-blown panic attacks, with heart palpitations and feelings of suffocation so extreme that he was convinced that he was having a heart attack.

Kabir was diagnosed with anxiety disorders, but not because he felt intensely anxious and worried. It was because he could no longer go to school, do activities, or keep friends. His way of coping had completely gotten in the way of his life. By attempting to avoid or suppress anxiety, it only made the anxiety stronger, which threw up roadblocks to learning how to cope. Though anxiety is a useful emotion, symptoms of anxiety disorders are worse than useless, because they actively get in the way.

Over 180 years ago, the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard wrote, “Whosoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate.” Be curious about your anxiety, and honor it. When we stop rejecting anxiety, and other messy parts of being human, we will be better able to channel, manage, and use it to prioritize what matters. When we rescue anxiety and reclaim it as part of being human, we stand a better chance of rescuing ourselves.

This article originally appeared in Next Big Idea Club magazine and is reprinted with permission.