- | 9:00 am

10 reasons why designers can be leaders who make a difference

10 big ideas on how designers can influence social and racial justice from the authors of Design for a Radically Changing World.

How can design make a difference? Design can be a catalyst for positive change and a signal that a community is valued and supported. While negligent environments can tear people down, intentional and positive design solutions can be used to heal, uplift, and unify communities, and to inspire hope for a brighter future.

Design for social and racial justice is about leading with hope. And it’s about actions and design principles that together have the potential to effect lasting change. No one action can manifest the change the world needs; instead, it is many actions by many people over time that will make the difference. As leaders of the largest design firm in the world, we are leaning into what it means to fight racism as designers, through our actions and interactions in our cities and communities.

Over the past several years, we have focused on 10 big ideas.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND COMMITMENT

Every design solution must embrace the surrounding community. The best designs happen when design teams engage with community and neighborhood leaders to create solutions that are informed by context and created in close collaboration with local stakeholders. This “local first” approach gathers participant perspectives to inform the design development process and ensure that resultant solutions address the most critical needs and opportunities for that place.

Engaging with communities to create more robust connections can happen only when passionate, on-the-ground teams build those connections directly. Gensler’s growing network of experts in community engagement has become a vibrant, distributed group of practitioners sharing tools and best practices to elevate these approaches on every project we touch.

DESIGN TO BREAK DOWN SILOS

Not every instance of racism and discrimination is obvious; some of the most pervasive spatial injustices are more subtle but just as damaging. Inequity can manifest in the form of neighborhoods with persistently lower home values, or with minimal investment in the public realm.

In the U.S., these situations often have direct links to redlining and historically racist real estate profiling and lending practices. Inequity also shows up in the form of highways or train tracks that cut through cities like walls erected to block unwanted visitors or divide communities. All too frequently, such infrastructure is built through neighborhoods whose inhabitants— often people of color—do not have the means or political capital to curtail these destructive developments.

There are many other disparities: broadband internet and bicycle lanes that become discontinuous and disappear the farther one gets from the highest-income areas of a city’s urban core; gendered bathrooms that are equal in size yet accommodate twice as many men as women; workplaces with so few maternal accommodations that women are forced to pause or abandon their careers to become mothers.

Each of these forms of ongoing discrimination and bias is the outcome of design decisions made in the past. Each is also an opportunity to leverage design as a transformative opportunity to restore equity and dignity to our communities. Instead of dividing, design can bring people together and elevate the human experience. Designers must seize the opportunity to create bold design solutions that break down the walls dividing our communities and instead create safe, welcoming spaces for all people, regardless of their age, race, sex, or other status.

PRIORITIZING ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

A critical step in fighting social injustice is to recognize how climate change disproportionately impacts marginalized communities and communities of color. Environmental racism is an issue with a long history that began to attract greater awareness in the early 1980s, when activists brought attention to the pattern of disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards experienced by disenfranchised communities and people of color in urban, suburban, and rural communities alike.

We must look for opportunities to address the inequitable effects of climate change. This begins with our own design work, at every scale and in every location. For example, a new research and education campus for the UCLA Congo Basin Institute in Central Africa—a collaboration between UCLA and the International Institute for Tropical Architecture—leverages passive and low-tech design strategies inspired by local architecture to optimize performance in the site’s unique climate.

ENHANCING THE PUBLIC REALM

During the most difficult parts of the pandemic, cities emptied of cars, buses, and trucks as people stayed home and mass transit agencies reduced or halted service. Pedestrians and cyclists took to the streets and were able to reclaim previously car-dominated urban spaces. Some municipalities responded by formalizing this trend with “Safe Streets” or “Open Streets” initiatives. While these programs have been a positive outgrowth of the pandemic, they were more commonly found in higher-income and majority-white areas—places already equipped with plentiful restaurants, shops, parks, and other cultural and leisure activities. Communities of color and disenfranchised neighborhoods, which typically see a significantly higher rate of pedestrians killed by vehicles, did not experience the same progress.

Safe and equitable urban mobility, access to green spaces, and walkable neighborhoods that promote well-being and connection are basic needs that every community deserves. Investments in this type of public infrastructure can make a significant impact. Think of Chicago’s lakefront, New York’s Central Park, or the parks of London. All are open spaces that belong to everyone, promoting inclusion and bettering the community.

DESIGNING IN—AND FOR—DISINVESTED PLACES

For too many industries and sectors, the places and types of investment that occur often align with whoever has money, power, and influence. Design projects largely come from a community’s owner class. Leading companies, wealthy families, and governments are the clients of the top firms of the world. By being proactive, we can expand our focus to include communities that are most in need.

This is a huge opportunity for the design industry. If we focus collectively on the disinvested places of our cities, communities, and countries, we can make a positive impact on our cities as a whole. Progress toward community resilience, live-work neighborhoods, and safe streets in disinvested places will benefit everyone.

SENSITIVITY TO UNIQUE COMMUNITY ISSUES

As we seek to design across our communities, we must acknowledge and respond to the unique history and issues each faces. For Black communities in the U.S., this could mean interrogating the legacy of redlining or disinvestment. Our Asian and Asian American communities are facing increased racism and violence in recent years, an issue in dire need of further attention. Caste- and status-related conflict continue to be pervasive in India, where hundreds of millions of residents are still considered “untouchable.” And in countries experiencing war, a deeper grasp of history can inform the ways in which we envision a better, more peaceful future.

Focusing on issues of particular relevance can help communities process and heal from traumatic events. In Minneapolis, in the area where George Floyd was murdered, Gensler is designing a new Pillsbury House and Theatre, which promotes creativity and neighborhood connections through the arts while supporting children and families. In London, our firm led the renovation of Your Space, a coworking and community center operated by Blueprint for All, previously known as the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust, which was established after the racially motivated murder of a young Black man who aspired to pursue a career in architecture. Your Space fosters community, networking, and collaboration among emerging architects, designers, and creatives.

PRIORITIZING INCLUSIVE DESIGN

As designers, we strive to create places where everyone will feel welcome. In the U.S., this includes meeting the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), but that’s only a first step. Inclusive design around the world requires designing for all people and incorporating design solutions that meet needs related to gender identity, race, ability, age, neurodiversity, or any other aspects of identity. A truly inclusive space will also help build a culture of inclusivity.

By integrating thoughtful programs and details into an existing space, an organization can signal that it truly cares about each person’s feelings of comfort, acceptance, and belonging. These initiatives—whether a signage program, an employee communications campaign, or a branding effort—can also bring renewed energy and relevance to the employee experience and make the workplace a more inclusive environment for all.

At Gensler, we dedicate time and resources to create a welcoming, inclusive, and supportive workplace that respects and values each team member as an individual with unique needs and evolving aspirations. We strive to foster a professional environment in which all people feel safe and seen, where their voices are heard and their concerns prioritized, and where everyone is empowered to pursue their passions and grow their career.

DIVERSIFYING THE DESIGN PROFESSION

Diversity is not just a goal to check off a list; it is a key driver of creativity and design excellence. Our capacity for design innovation grows when we embrace the perspectives of individuals from different places around the globe, backgrounds, and cultures. We know this from firsthand experience: Gensler is one of the most diverse firms in its field. Nearly 8 percent of our firm identifies as LGBTQIA+. Thirty-five percent of our firm is Black, Hispanic/Latinx, or Asian. More than half (55%) of our employee population is female, and half of the members of our Board of Directors are women—notable ratios for a large, global firm operating in a sector that has traditionally been dominated by men.

We must continue to push for even greater diversity. Creating a more diverse profession of tomorrow requires action today. To grow and support this next generation, we are doubling down on our mentorship and educational activities by partnering with groups such as the ACE Mentorship Program and the National Organization of Minority Architects. We have also partnered with the seven Historically Black Colleges and Universities architecture programs to create an annual series of design charrettes that bridge academia and professional practice, fostering lasting relationships between faculty, students, and Gensler mentors. The core curriculum of the program is rooted in our firm’s mission: embracing the power of design to create a better world.

PARTNERSHIPS AND PEER COLLABORATIONS

As we build a more diverse design profession, it is important to seek out diverse partners. Collaborations can be the key to creative problem solving and incredible design innovation. This is especially true when we prioritize partnerships with local, small, and diverse firms and consultants. By partnering with the work of these teams, Gensler and our global peers in the design and real estate industry have an opportunity to grow the experience, connections, and portfolios of these firms, elevating the profession while investing in equitable design and diversity at scale.

Gensler has a strong legacy of partnership. From large airport projects to local corporate projects, we have been able to work with firms around the world across a diversity of scales, cultures, and expertise. For example, today we are in partnership with Moody Nolan, the nation’s largest Black-owned architecture firm, to design the new Columbus International Airport.

TRANSPARENCY, RESOURCES, AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Gensler’s people-first culture and commitment to diversity have always been at the core of who we are. However, in 2020, to ensure a more intentional and informed path toward our goals to support diversity and inclusion, we established our Five Strategies to Fight Racism. A cornerstone of the approach was a commitment to increase racial diversity in the firm. We decided to publicly share our demographic data, in order to make our metrics and progress more transparent, and in 2021 we published our inaugural diversity report, “Leading by Example.” The publication— the first of its kind in our industry—established accountability and momentum across our efforts to increase diversity within Gensler.

Understanding the complex connections between the built environment, injustice, and inequity is not an easy task, but it is essential for the wellbeing of our communities, cities, and world that we engage with the hard questions and take action. As designers, we must champion justice, equity, and inclusion in every project we touch. We must use design to bring hope.

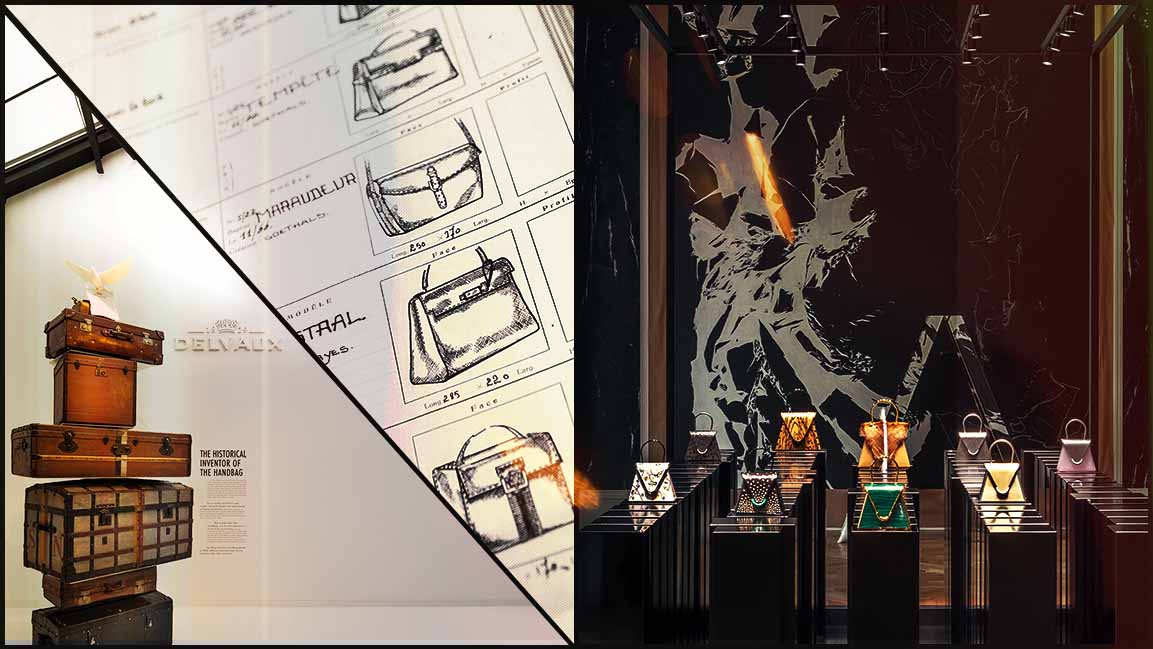

This excerpt is used with permission from the book Design for a Radically Changing World by Andy Cohen and Diane Hoskins. The book shows the impact of design on our everyday lives and offers innovative ways that design can help address some of the world’s most pressing issues affecting our cities and communities, including the ongoing need to design cities to be more inclusive and accessible to more people.

Delve deeper into the design-thinking process and global design trends, encompassing urban planning, biophilic design, immersive technologies, and more, at the Innovation By Design Summit, partnered with Msheireb Properties, in Doha on April 24. Attendance at the Innovation by Design Summit is by invitation only. Delegates can register here to receive their exclusive invite.