- | 7:29 am

Forget chief sustainability officer. The latest job in architecture is director of biomimicry

Let’s talk about elephants for a second. These magnificent mammals have been on this planet for over 55 million years. Many of them live in dry, arid climates, so they’ve learned to stay cool thanks to the fine network of wrinkles on their skin, which helps them trap moisture and stay cool.

What if buildings could do the same?

Jamie Miller [Image: courtesy B+H]

This question is the core principle behind the ever-growing practice of biomimicry, or the act of imitating nature’s designs and processes in man-made systems. Think plane wings modeled after a bird’s wings, or Velcro inspired by the tiny hooks at the ends of bur needles. Popularized by American biologist Jenine Benyus in 1997, biomimicry is now seeing renewed urgency as a design solution to the climate crisis.Jamie Miller has been putting principles of biomimicry into practice since 2007, consulting for design firms, and teaching Canada’s only biomimicry program at OCAD University. A designer and engineer, Miller was trained by Benyus herself, then went on to found his consulting company Biomimicry Frontiers. Now, Miller has been hired as the first director of biomimicry at B+H, a Canadian architecture firm with projects around the world. His title is one of the first in the field of architecture—but it hints at a significant shift of perspective in an industry that has long been fighting nature, instead of working with it.

A FRONTRUNNER IN BIOMIMICRY

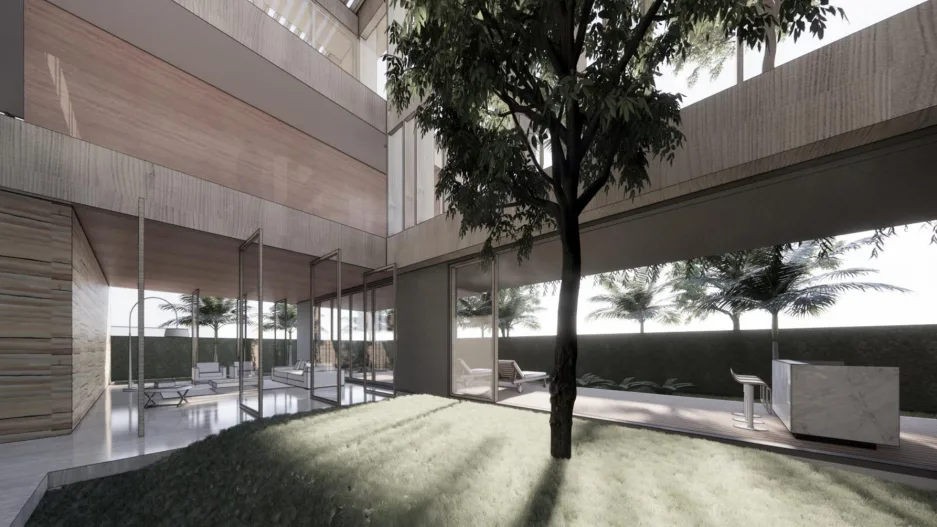

Since he joined B+H in November of last year, Miller has been involved in several residential master plans from Ontario to Gabon, as well as the design of a residential house in India. He says that forest canopies, mangroves, and silk spiders can all teach us how to design more efficient, sustainable buildings. For the design of the house in Bengaluru, India, for instance, the firm is using various cooling strategies inspired by elephant skin and termite mounds, all the while recreating a garden ecosystem inspired by how forests work. The elephant skin, for example, inspired them to create a passive cooling wall made of stones stacked on top of each other, while the termite mounds inspired the design of multiple vents that pull in cold air and push out hot air, much like the tunnels inside a mound. “What’s exciting is that we’re now exploring how to embed biomimicry into all facets of B+H,” he says.

[Image: courtesy B+H]

Miller had consulted for B+H for years, but he says that being an integral part of the team allows him to build relationships much faster and inject biomimicry principles into areas like interior design and experiential design, too. “Having me on board allows me to be pulled into any team,” he says.

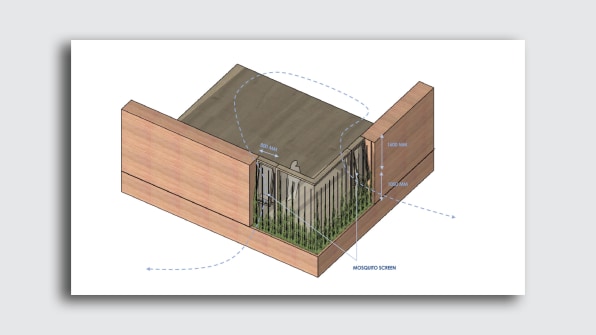

[Image: courtesy B+H]

A SIGN OF PROGRESS

In recent years, the dramatic rise of chief sustainability officers—in design and architecture, but also among Fortune 500 firms—has shown the increased importance that organizations are placing on environmental issues. But for Miller, biomimicry isn’t just a subset of sustainability, it’s the foundation. “Biomimicry is the only model of sustainability we have, based on how long it’s been around and how few years humans have been around,” he says.

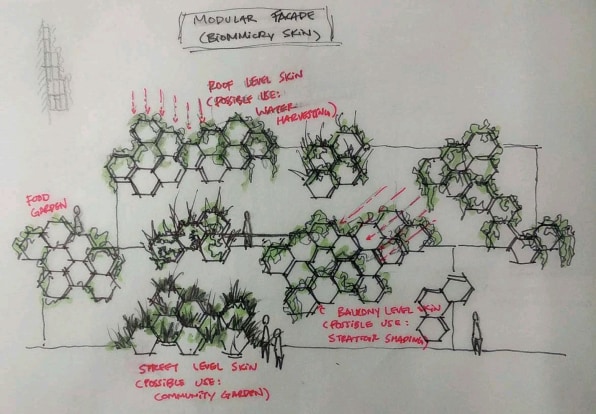

[Image: courtesy B+H]

The reality is, we are a young species, comparatively, while nature has had plenty of time to teach trees how to pump water from their roots to their top leaves, and termite colonies how to build mounds with tunnels for ventilation. “Once you see that nature is the culmination of billions of years of time-tested solutions, you move away from something to exploit towards something that can really teach us,” says Miller.

[Image: courtesy B+H]

A TOOL FOR CLIMATE CHANGE

In the end, Miller sees biomimicry as a driving factor to mitigate climate change, which has long been labeled as a “wicked problem” because it relies on so many interdependent factors that it can seem impossible to resolve. Miller, however, believes solutions are difficult because we keep drawing on past ideas and perpetuating the same mistakes we’ve always made. “Biomimicry allows us to step aside and look at the world differently,” he says.

[Image: courtesy B+H]

Ecosystems are great at sequestering carbon, while silk spiders have perfected the art of weaving a very strong material without exerting any energy (compared to, say, the energy we use to extract materials and construct buildings). “We have to shift the paradigm we use to design and let nature into it,” he says, not just by making room for greener spaces, but also by finding ways to integrate the kinds of processes we see in nature into the building environment. For our buildings and cities to really emulate nature, however, we need to go back and redesign the building blocks that make up our buildings, both literally and figuratively. If we want adaptive buildings, we need to design adaptive materials. If we want low-energy buildings, we need to come up with low-energy processes.

And if we can’t figure out how to do it, then we should look to nature—because it probably already has.