- | 9:00 am

Here’s what Frank Lloyd Wright’s unbuilt designs would look like today

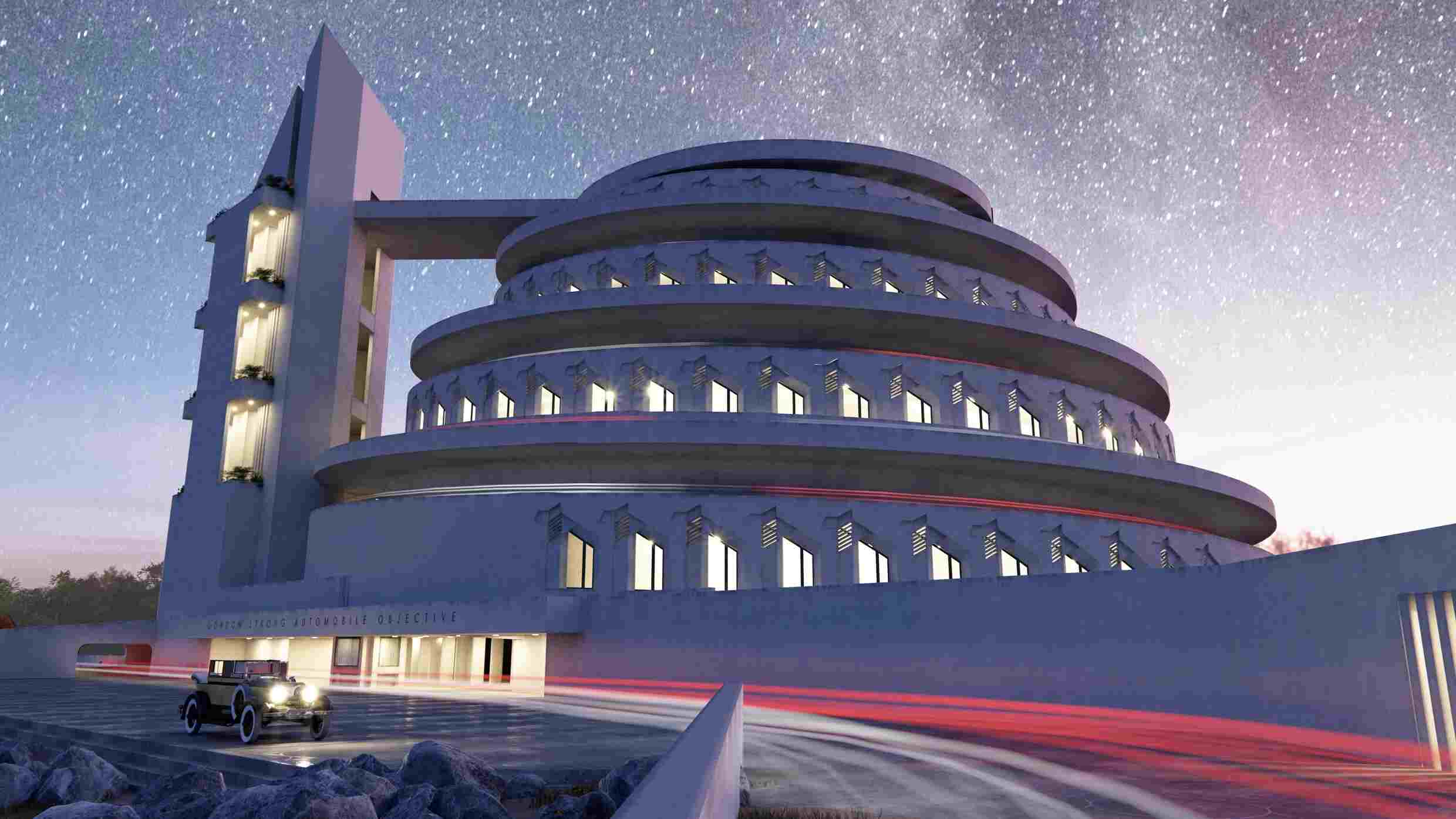

More than 660 of Wright’s buildings never saw the light of day. Architect David Romero has built elaborate 3D models to bring some of them to life.

Frank Lloyd Wright needs no introduction. With over 530 built works, mostly in the U.S., he is one of the most prolific architects of the 20th century. But for every building he completed, there’s a building that never saw the light of day. More specifically, more than 660 of his projects are still sitting flat on a piece of paper, unlikely to ever take shape in the physical world.

Over the past four years, however, one Spanish architect has been painstakingly reimagining some of Wright’s unbuilt buildings (and some demolished ones) into elaborate 3D renderings. Together with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, David Romero has created over a dozen virtual models of Wright’s buildings, many of which are only known to Wright’s most reverent fans.

![Roy Wetmore [Image: © 2023 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ]](https://wp-cms-fastcompany-com.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/01/20-90841299-frank-lloyd-wright-unbuilts.jpg)

Each of these models was developed under a different theme. In one series, Romero featured buildings that Wright designed on the water, like his floating cabins on the Lake Tahoe Summer Colony. In another, he focused on structures Wright designed for the car, like a snazzy showroom with a ramp for a roof and a car perched at the very edge of it. In his latest series, Romero shines a spotlight on Wright’s unbuilt skyscrapers, including his 1956 proposed mile-high, 528-story tower intended for Chicago known as The Illinois, for which Wright could never find a client. He also created a rendering for the glassy National Life Insurance Building in Chicago, which would have been among the first glass curtain wall buildings in the U.S. had it been built when Wright designed it in 1925.

![[Image: courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]](https://wp-cms-fastcompany-com.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/01/05-90841299-frank-lloyd-wright-unbuilts.jpg)

The goal of Romero’s series is not to get these buildings constructed today. The Foundation has an “unbuilt buildings policy” that outlines the various reasons why it declines requests for plans or permissions to realize Wright’s unbuilt designs. For starters, any building constructed today would likely be built using materials that weren’t available during Wright’s time, so the contemporary version of those buildings are inherently going to look different, “and therefore inauthentic,” says Stuart Graff, president and CEO of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. On the other hand, many of Wright’s realized buildings are threatened with demolition and in need of constant advocacy and preservation work. “To spend millions to build unbuilt works while the ones he actually built don’t have adequate funding doesn’t seem like right thing to do,” says Graff.

So, what makes collaborations like this so noteworthy? Like the foundation’s recent partnership with Steelcase—which reimagined 1930s office furniture from Wright’s SC Johnson building into a brand-new home-office collection—these 3D renders continue to raise awareness and cement Wright’s legacy in the present. They also help introduce the architect’s lesser-known projects to a new audience.

![Masieri [Image: © David Romero/courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]](https://wp-cms-fastcompany-com.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/01/13-90841299-frank-lloyd-wright-unbuilts.jpg)

![Masieri [Image: © David Romero/courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]](https://wp-cms-fastcompany-com.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/01/12-90841299-frank-lloyd-wright-unbuilts.jpg)

For Graff, projects like Romero’s help convey ideas that can inform the work of future architects. “Right now, we face challenges about remodeling the urban cores of our cities, as working from home or remote wok become more important,” he says. “Wright was envisioning this very thing 100 years ago, and drawing plans and creating thought experiments to explore better modes of building and living to comfortably accommodate a changing social landscape,” he says.

For example, in his ambitious Broadacre City concept, visualized by Romero in a previous series, Wright envisioned a “decentralized” city where each family would own at least an acre of land to grow their own crops, and artists could have a greater role in designing the built environment. The vision had its flaws—one of them being the inevitability of urban sprawl—but it certainly merits a place in contemporary conversation.

Romero estimates that his virtual model of Broadacre City took him a full year of his free time to complete, or about 100 hours. The Illinois took about 50. Romero relies on existing graphic material to make a computer model. He says Wright’s original drawings were in color (“thank God”) and blueprints come with various degrees of detail. If he ever needs to cross-reference, he says material from built projects help too. “For the Guggenheim Museum, there are almost 800 drawings,” he says.

![Seacliff [Image: courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]](https://wp-cms-fastcompany-com.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/01/06b-90841299-frank-lloyd-wright-unbuilts.jpg)

Once the model is complete, Romero starts working on materials, textures, and the kinds of everyday details that lend realism to the image, like cars and trees. To show The Illinois in Chicago’s proper context—remember, it would’ve risen to a whopping 528 stories—he had to buy a model of the entire city of Chicago. For every project, Romero aims for beauty, but also authenticity. “This is the closest thing to physically visiting them that we will ever be able to do,” he says.

The process comes with challenges, and some details will inevitably be missing. To fill in the gaps, Romero asks himself: “What would Wright do?” For example, when Wright set out to design the Trinity Chapel for the University of Oklahoma, in 1958, he only drew parts of it. This left Romero with sketches and plans of the building, but nothing about the design of the pulpit, the furniture, or even the stained-glass windows. “The result, especially of the interior, is not 100% Frank Lloyd Wright, but rather my interpretation of how Frank Lloyd Wright would have done it,” he says.

We’ll never know how Wright would feel about Romero’s interpretations, but such is the nature of the endeavor—a blessing and a curse at once. The architect recalls a quote about the difference between the novelist, who records facts and interprets them, and the historian, who merely relates the facts. “My work is not very different from that of a novelist,” he says. “After reading all the texts and studying all the drawings, I have all the ingredients, but I have to cook the dish myself,” he says.

![Seacliff [Image: © David Romero/courtesy The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]](https://wp-cms-fastcompany-com.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/2023/01/16-90841299-frank-lloyd-wright-unbuilts.jpg)