- | 8:00 am

Photography is inherently racist. Can new technology change that?

How Google and Snap are creating new technology to fix an age-old problem: racism in photography.

The cinematographer Jomo Fray has only two photos of his Carribean grandmother, likely taken in the 1950s. Though he considers them exceptionally well shot, Fray recalls that she hated being photographed because she never felt the pictures looked like her. “Photography was fundamentally not designed to capture people with dark skin,” Fray says, a technological bias with deeply personal consequences. “If we believe the sentiment that we only die the moment the last person remembers us, that’s the power of a photo.”

Though nearly everyone has a camera built into their phone and images saturate our culture, technology is still catching up in its ability to capture a range of skin tones. The foundational principles of film photography that considered light skin the default, including exposure theory and color mixing, have been built into digital technologies from the start. And it’s well documented that AI, which has powered recent advancements in photo technologies, is rife with racial bias. The result is that we live in a world where it’s shockingly easy to create a clear picture of the Pope wearing Balenciaga (which never happened), but if you try to actually take a photo in iffy lighting of nonwhite children smiling and blowing out candles on a birthday cake—well, that can be a crapshoot.

Heeding consumer demand for better image-making tools, tech companies have started to correct for racial biases in digital photo technology, including those that persist from the days of film and that have been built into AI.

INNOVATION FROM GOOGLE AND SNAP

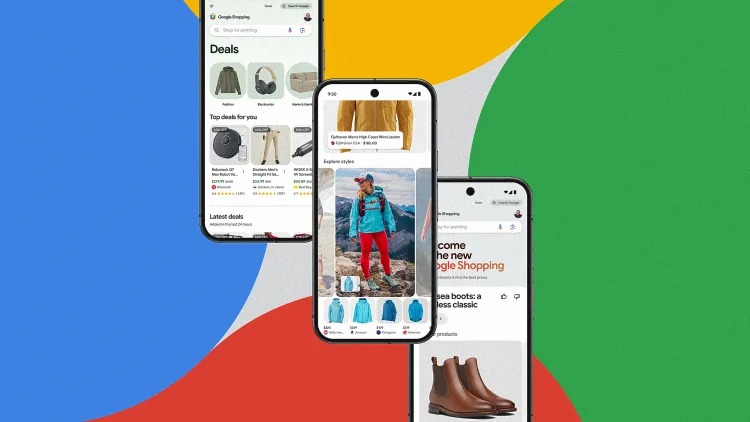

Google last year introduced the Pixel 6, its first mobile phone featuring Real Tone, software that leverages AI to capture a broader range of skin tones. Fray, one of the artists who consulted on Real Tone’s development, says he spoke with engineers not just about refining image quality, but also understanding how biases in technology came about. “If we can have conversations about the nature of the technology and its history, we can get to a place of more robust and inclusive imagery,” Fray says.

Photographer Joshua Kissi (left) and product lead for Snap’s Inclusive Camera Bertrand Saint-Preux; Tone Mode was developed in partnership with six professional photographers including Philmore Ulinwa, Brian Freeman, Tara Rice, Emery Barnes, Christopher Malcom, and Samuel Alemayhu. [Photo: courtesy of Snap Inc.]

Similarly, Snap’s Inclusive Camera aims to improve Shapchat’s ability to accurately capture its diverse range of users. “As a Black engineer at Snap, I related how we developed our camera to my personal experience with them,” says Bertrand Saint-Preux, who first pitched the project in the summer of 2020, when interrogations of anti-Black racism erupted across industries. “Cameras have evolved and become better at capturing different skin tones, but there is a lot more work to do,” Saint-Preux says.

Exposure theory and color mixing are two of the major principles of film photography that are still causing trouble in digital tech. The Zone System, developed long ago by Ansel Adams and Fred Archer around 1940, divides exposure range into 11 zones—from pure white to pure black with nine shades of gray in between. Zone VII, or 18% gray, was long considered the optimal exposure for people in a photo, a standard that Fray notes was based on white skin. Though the Zone System was devised for black and white film, it has also formed the basis of exposure theory in color film and digital-photo technology.

AI ADVANCES, BUT RACISM PERSISTS

The cameras we use on our phones are programmed to make adjustments without expecting us to have any expertise. Where early digital cameras were programmed to automatically average out the range of skin tones in a photo, optimizing for the middle gray associated with light skin, developments in AI have made that process more dynamic. But inherent bias is still obvious. Take the example of NFL player Prince Amukamara’s apparent disappearing act in a picture taken only last year with white peers. The phone camera pointed at the three Packers players optimized exposure for Aaron Rodgers and Brett Favre while leaving Amukamara in deep shadow. The result is startling proof of the values built into the technology about who is worthy of being seen.

The chemistry of color film, which is composed of layers sensitive to different colors of light, was also formulated to render light skin tones. In the 1950s, Kodak introduced the Shirley Card, a photo of a white woman likely named for the employee pictured on the first one, as a standard for film developers to determine color balance. It wasn’t until the 1970s, when companies advertising wood furniture and chocolate bars complained that Kodak film didn’t differentiate between shades of brown, that Kodak worked to expand its film’s color palette. By the 1990s, Kodak touted the ability of its Gold Max film to “photograph the details of a dark horse in low light,” a loaded way to say it worked better with dark skin tones. It was around the same time the company added women of different races to its Shirley Card.

THE MANY SHADES OF SIMONE BILES

Achieving color balance still remains a complex process, even for professional photographers. Consider how many different shades Olympic gymnast Simone Biles has appeared on magazine covers. It’s reasonable to assume that tech innovations would address such complications. And yet recent examples of bias in AI have been downright disturbing, like an algorithm that was fed a low-quality image of Barack Obama and produced a sharper one, enhanced by AI, that transformed the former president into a white man. AI photo technology is only as inclusive as the data it’s fed—one area in obvious need of overhaul.

Outcry over such highly visible blunders has, in part, led to the latest push for change. Snap’s innovations address limitations in exposure and color-balance technology that persist in digital cameras. Improvements to Snapchat have included “computational photography algorithms that correct exposure” and a new ring light feature for using the app at night—“with options to change the color temperature and tone, which improves the areas in the face that are over or underexposed,” Saint-Preux says, adding that Snap is also leveraging its augmented reality (AR) technology to improve image quality.

Product lead for Snap’s Inclusive Camera Bertrand Saint-Preux; this feature works by expanding the Camera’s dynamic range, improving both over- and underexposure in order to best capture Snapchatters of all skin tones and create a more inclusive experience. [Photo: courtesy of Snap Inc.]

The advent of social media provided the first major push toward innovation. The rise of streaming—combined with a shift toward more diverse representation in television and film—is further driving the evolution of how stories are captured, and what expectations people have when they turn to see themselves reflected on a broader scale. The cable series Insecure and P-Valley and work by Black filmmakers, such as Barry Jenkins, have drawn particular acclaim for the depth and richness of their approach to dark skin tones. “Capitalism innovates toward demand,” notes Fray. “The tools need to be better and are being forced to grow in the direction that artists are taking them as stories become more inclusive.”

How darker skin tones are rendered on screen “really depends on whose story is being told,” says Julian Elijah Martinez, an actor on the Hulu series Wu-Tang: An American Saga, who is also a photographer. Wu-Tang’s creative team has taken “extra care to make sure the world is lit in a specific and intentional way,” Martinez says. “But when you’re on a show like Law & Order, they’re lighting for the general mood of the show and trying to make sure that every episode feels the same.” As a result, Martinez’s skin may look faded or blown out compared to how it looks on shows with an overarching aesthetic that’s tailored to darker skin.

Julian Elijah Martinez (left) and Ashton Sanders in Wu-Tang: An American Saga [Photo: Jeong Park/Hulu]

“I find that a lot of Black and brown skin reflects color, but not necessarily light,” while white skin does the opposite, Fray says. “Someone like Liv Tyler is almost porcelain in her skin tones, so when you put light on her, it radiates light back out. But when you blast darker skin tones with light, it can make Black and brown people look ashy or anemic.” Using color to draw out the hues of melanated skin is one often-used creative technique. “Underexposing and adding color can help the camera render darker skin correctly,” Fray says.

T.J. Atoms (left) and Julian Elijah Martinez in Wu-Tang: An American Saga [Photo: Jeong Park/Hulu]

The expansion of dynamic range, or a camera’s ability to accurately capture a wider spread of skin tones within the same frame, is an area of innovation that creators and photo enthusiasts hope to see advance moving forward. It’s especially relevant as families, communities, and the stories that are told about them grow more cross-cultural and diverse, a demographic reality that’s essential for technology to be able to capture.

“Thinking inclusively about the image isn’t just about seeing yourself accurately represented in the present,” says Fray, “it’s about the images that survive you. As a culture, we understand our present by understanding our past. Photos are a large part of that.”