- | 8:00 am

This 3D-printed air-conditioning ductwork could solve one of the office’s biggest problems

A more sustainable approach to air conditioning, inspired by frog skin.

For all the reasons workers might hate their offices, air-conditioning ranks highly. One study found that 60% of workers reported thermal stress in their too-cold workplaces, and thermostats have long been set down low for the long-gone age of offices being stuffed with men in three-piece-suits. Offices are often too cold, particularly for women, and everybody’s productivity suffers.

But what workers hate is not the air-conditioning itself. It’s the way that air-conditioning is distributed: through snaking overhead tunnels of metal ductwork and out the end of just a few vents along the way.

“Traditional ductwork dumps air wherever there’s an outlet,” says Neil Logan, co-CEO of the Australian architecture firm BVN. “You get lots of complaints from tenants because typically the person sitting underneath the air diffuser is freezing cold, and the person who is not is typically hot.”

BVN set out to rethink the vented duct, which has been an industry standard practically since the advent of air-conditioning more than 100 years ago. “It’s not changed since then,” says Logan. “No one had really asked the question about ductwork.”

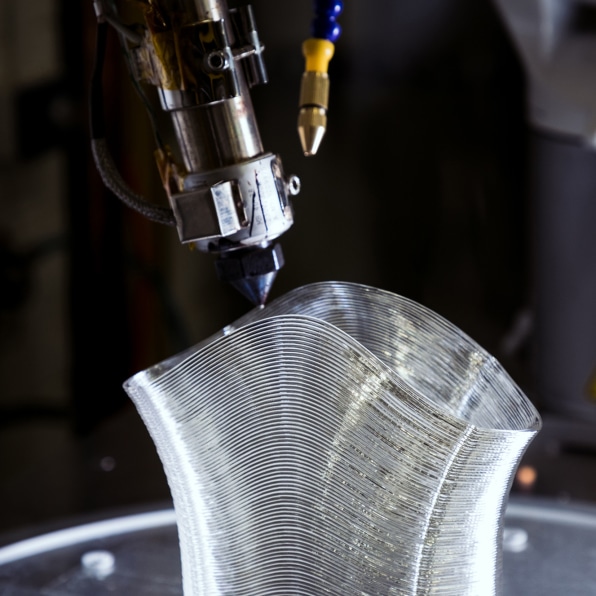

BVN reimagined the ductwork as a branching network of 3D printed plastic tubes that allow air to seep out evenly through a space. The designers realized that relying on just a few points of exit for cold air was air-conditioning’s key problem, and they began to look for ways to more evenly distribute air without sacrificing cooling efficiency. They also wanted to find ways to cut down the carbon impact of air-conditioning, from both and energy consumption perspective but also from the embodied carbon emissions within the air conditioning system’s materials. One recent study found that HVAC systems represented between 15% and 36% of the embodied carbon in a typical office building.

“Aluminum ductwork is a huge part of that,” Logan says. “So we asked can we think of these components in a different way using advanced manufacturing techniques that gets us a better outcome.”

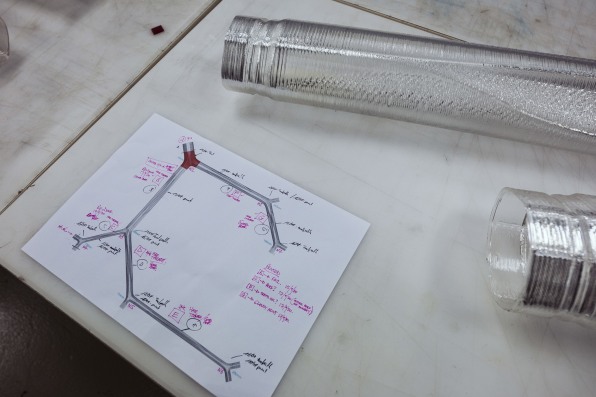

The team found a lower impact replacement through 3D printing recycled plastic. Through studies of air flow and fluid dynamics and algorithm-based computational design, they developed a narrow, oval shaped duct profile with gently branching connectors that move air more smoothly than the often rectangle-shaped ducts that connect at hard right angles. The limited vents in a conventional system are replaced by periodic perforations in the tubular surface of BVN’s ducts. These holes were inspired by the pores in a frog’s skin, and allow air to seep out through the length of the ductwork in a near uniform flow. To work in an office setting, the ducts would need to be exposed on the ceiling, not hidden away behind drywall. With a more elegant design than conventional ducts, this is framed as a feature of the concept.

The system was installed in BVN’s Sydney studio, where its efficiency has been undergoing tests. Using heat sensors, the designers have found that the system distributes air more evenly throughout the office while saving 10% of energy use and 90% of the embodied carbon of aluminum ducts.

The ductwork was also designed as a kit of parts, with standardized fittings and components that can be combined in a wide variety of branching layouts to service offices of nearly any size.

For now, the system is just a proof of concept, and Logan says the firm is in talks with several clients about installing systems in new buildings. These live installs would allow the system to go through usage and fire rating certifications, which would put the system in compliance with building codes and enable wider use. “There’s definitely a curiosity from a number of clients,” Logan says.

More importantly, he notes, is the interest the firm has heard from manufacturers in the duct industry. Logan says the system was deliberately designed with the kit-of-parts approach in hopes that it could eventually become a common product. The duct industry would be a natural partner to take the concept to scale. When that industrialization might happen is an open question. But if this idea were to spread, it could give workers one less reason to hate the office.