- | 9:00 am

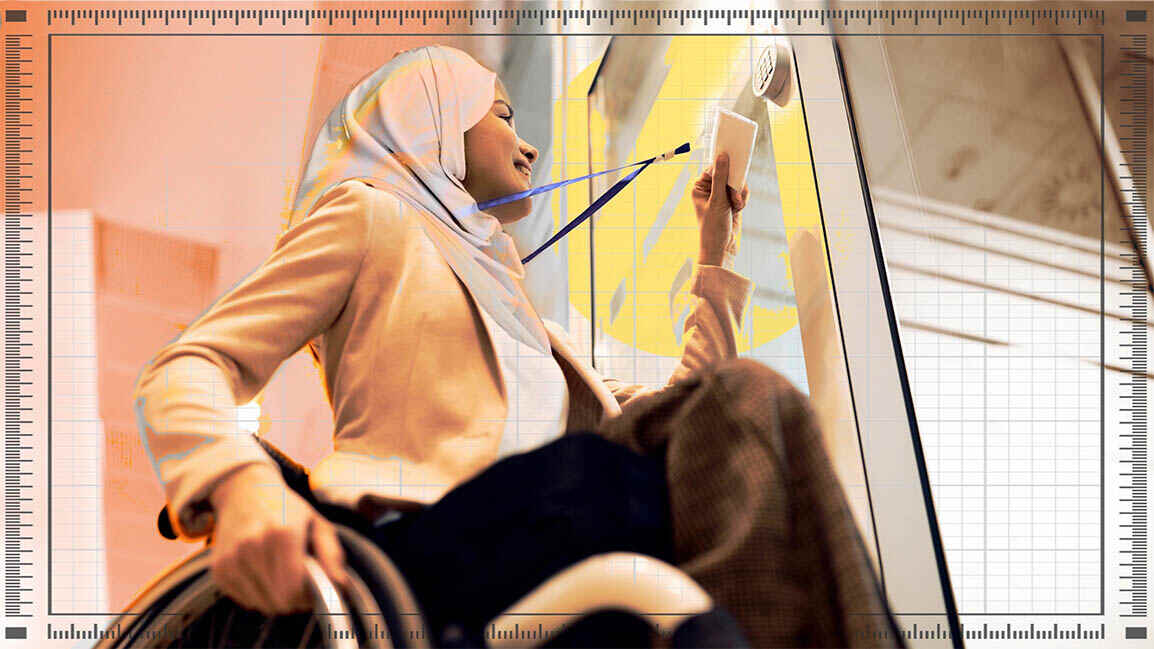

Workplaces are inaccessible for people of determination. Inclusive design can solve that

Accessibility hasn’t been prioritized. Experts say employing an all-inclusive design practice and providing a great user experience that empowers people of determination can be a start.

We often see office spaces that, at first glance, seem wheelchair accessible with a ramp and level access into every part of the building. However, a quick tour will show that only half is accessible for people of determination.

Nowhere is this more pronounced than for the Middle East’s 30 million people of determination. For the majority of these people, having an accessible workplace is impossible. To provide support and make workplaces more productive for current and future employees who are people of determination, designing an effective inclusive workplace with adequate consideration of mobility and access to community spaces and services is essential.

“It should be a priority for every company to ensure that they deliver the right environment for their employees to perform, learn, develop and thrive,” says Marilena di Coste, founder of The Butterfly, an advocacy group in Abu Dhabi, on a mission to empower people of determination and help them to advance in the workplace.

So how do we make a workplace accessible for all?

To start with, workplaces and lounges must be barrier-free, with wider gates and tactile guidance, drive-through lifts, so wheelchair users don’t have to turn around, and small, tactile knobs on railings so visually challenged people can easily tell which floor they are on. Lift doors should stay open longer, handrails at both sides of staircases, and chairs must have grab handles.

“We need to address that we unconsciously create barriers for the people of determination. The design community needs to flip the design narrative by designing first for people of determination, so we design for diversity within the human spectrum,” says Dr Harpreet Seth, Associate Professor, Head of Architecture and Director of Studies, School of Energy, Geoscience, Infrastructure and Society at Heriot-Watt University Dubai.

DESIGNING IS AN INCLUSIVE ACT

According to Seth, good design is “more than accessibility as an outcome; it’s more about inclusive design as a process.”

At a planning level, designers need to address this process by employing an all-inclusive design practice, prioritizing a great user experience that empowers people of determination, and removing the barriers between the user and the space in a human-centered approach. “Recognize exclusion and generate new innovative solutions for opportunities for all,” she adds.

Designing is an inclusive act. Echoing Seth’s sentiment, Gionata Gatto, Assistant Professor of Product Design at the Dubai Institute of Design and Innovation (DIDI), says, “it’s not a matter of prioritizing the needs of people of determination, but more so trying to be as inclusive as possible throughout the design process.”

Today, it’s about more than designing spaces that ensure people of determination are not left behind. “Our spaces had improved greatly since the ’60s when the discussion around accessible design began. Now, the task is even greater. We know more about what being differently abled means, so we need to have a comprehensive understanding and make them comfortable.”

It is commonly thought that a workplace is accessible if there is an adjustable height desk to sit at. According to experts, places like kitchens, toilets, prayer rooms, and changing rooms can present barriers to mobility-impaired employees if appropriate planning is not implemented.

An open-plan office should consider how easy it is for an employee in a wheelchair to navigate to their desk. Also, if that person needs to have frequent contact with their line manager and team, consider where everyone in that team is.

It’s a fact that people of determination have less access to services, social activities, and green spaces. “Day to day, we do not see many people of determination engaging in social activities or enjoying green spaces,” says Seth.

According to experts, it’s time to have a conversation on the “liveability” of our spaces. How liveable, safe, and inclusive are our public spaces? Over the last decade, market-driven approaches to people of determination have led to limited design diversity, innovation, and choice.

“Spaces should be designed in a way that they are accessible and inclusive for all. The inclusive design seeks to create a safe workspace where people, irrespective of differences, can work efficiently without needing to adapt them specially,” says Di Coste. “This is essential to ensure the workplace does not segregate employees based on their specific requirements. Workplaces should allow everyone to feel supported and comfortable.”

Although many cities in the Middle East have accounted for the diversity of people and their needs, there’s still room for improvement. In 2016, Dubai, one of the most accessible cities in the region, embarked on a $2.7 million study to make schools, hospitals, parks, and transport accessible for all.

But inaccessible workplaces and public spaces are a daily occurrence for most people of determination. According to di Coste, the Dubai Universal Design Code, which encourages accessibility, should be applied at the earliest stage in the design process to make spaces as accessible as possible.

“All spaces can benefit from being designed to be as inclusive as possible within necessary constraints, be they physical, budgetary or other,” she adds.

It is also helpful to consider the journey to and from the workplace for those with disabilities. Public transport systems and adaptable public spaces support are enablers for a more effective workforce reducing reliance on family and friends.

“There have been positive steps in the region with access to public transport and services. For example, in Dubai, people of determination have worked with the Road and Transport Authority to include more ramps across Dubai’s public transport systems,” says Seth.

DESIGN DRIVEN BY COSTS AND TRENDS

Obviously, more needs to be done. Adequate consideration of mobility and access to office spaces and services is necessary. We know the workplace can have positive and negative effects on health, from determining activity levels to our contact with colleagues.

Costs and wide-scale trends generally drive commercial office space designs. When required, workplaces may meet the minimum accessibility requirements but almost never consider the end-user needs. This can create inappropriate environments, which then require modification for individuals—a wasteful and costly approach.

Short-term gain and short-sightedness override the end-user needs and experience in the design of commercial buildings and workplaces, says Seth. “The constraints imposed by tight timelines and budgets create a scenario where the commercial gains come first, and the user is secondary.”

“Addressing end-user needs and good user experiences don’t happen by chance. They are purposely designed through an iterative design process that can create a solution that meets both business and end-user needs,” adds Seth. “This requires time and research into the users’ characteristics, behaviors, needs, and context of use. Most importantly, people of determination are often not included in ‘end users,’ and this is where inclusive design needs to be put to practice.”

When designing a space for people of determination, the process involves gathering information through different methods, then ideating, prototyping, and testing ideas. “Designers’ engagement with people of determination is usually limited, as is their role in the design process,” says Gatto.

At DIDI, students are inverting this route. Last year, DIDI collaborated with Dubai’s Al Noor training center, an institution that provides professional care and training to people of determination to develop solutions to their problems together.

“We teach students the value of designing ‘with’ those who live with a (dis)ability, as opposed to just designing ‘for’ them. This is a fundamental shift, as it suggests that who we call ‘user’ is an actual expert of their own life and, as such, should be engaged as a fundamental actor in the design process,” he adds.

“This way of thinking and doing is leading to a number of great projects, currently incubated for further development at DIDI.”

Accessibility at workplaces must be felt but not seen. For people of determination, independence is being able to go about their day, get to wherever they need to be, and do whatever they need to, without asking coworkers to help.

“It is important that we do not reinforce feelings of difference or segregation and replace them with feelings of integration as physical accessibility does not always equate with motivation to visit. This comes from socio-cultural factors of feeling welcomed, safe, and comfortable,” Seth adds.

Indeed, perception affects inclusion. Ramps and doorways mean little unless paired with social confidence.