- | 9:00 am

This futurist believes that human ingenuity can save the world

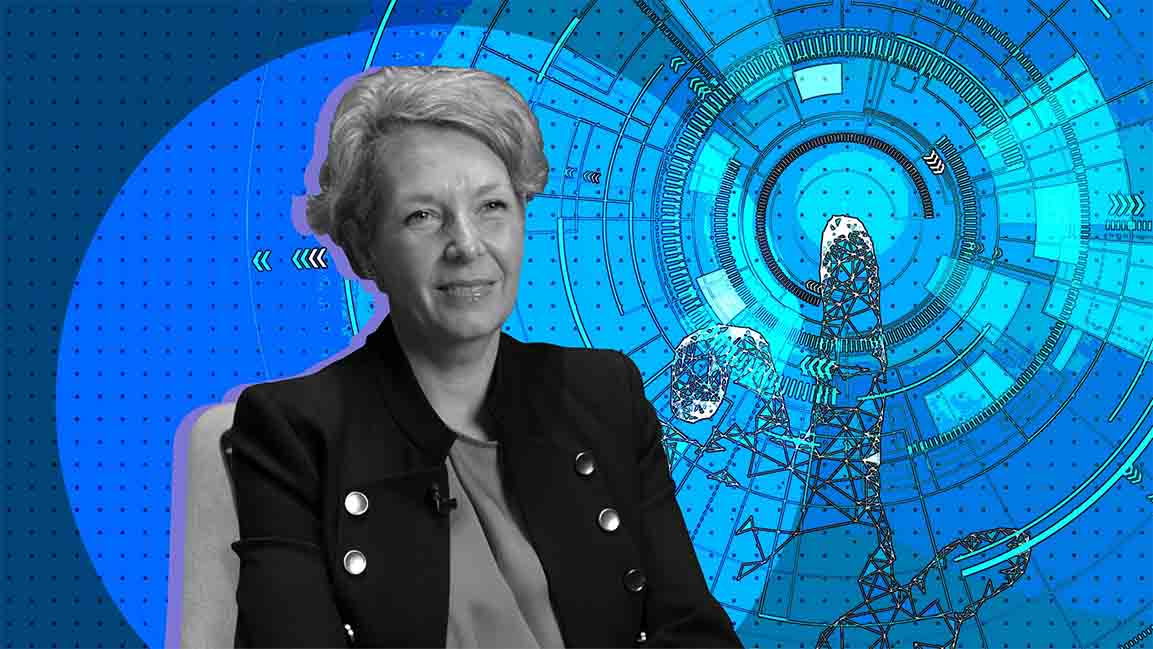

In an exclusive interview, KD Adamson says we're in liminality when big thinkers and doers appear to solve pressing problems of the day. And humans, not technology, will fix climate change.

“Lately, I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end. The best is over,” Tony Soprano tells his therapist in The Sopranos. While many feel these are the twilight years, with hundreds of millennia of human activity stretching back behind us, some are unapologetically optimistic.

Futurism is a dangerous game. It can go awry.

And from our vantage point in 2023, when technology has made great leaps and bounds, predictions about flying cars, teleportation, or faster-than-light travel in the near future seem banal.

Technology does save the day and then some. And many have said that by 2050 computational machines will surpass the processing power of all the living human brains on Earth, and we all need to work together to survive.

This sort of thinking has come to be known as the singularity: the idea that there will be a point, a singular moment in time, when the ability to think machines outstrips those who created them and progress accelerates with dizzying results.

“Well, it’s a very popular idea these days to think that the future is a technology problem. This has led many people to think that the future of humanity is basically a technological singularity,” says KD Adamson, a leading futurist and ecocentrist, as we sat down to talk about the future of humanity.

WATCH THE VIDEO HERE

UNCERTAINTIES OF THE FUTURE

She says we are not moving into a singularity but into liminality. A liminal period is a threshold of the future where past certainties have been dismantled, but what’s going to replace them is still uncertain.

“It’s very contested at the moment in the future. And liminal periods are interesting because it’s when you find really big thinkers and doers that appear. It’s a period when people can…,” adds Adamson, partly cautiously upbeat.

The UN predicts that roughly 60% of the world’s population will live in cities by 2030, meaning 6 billion of us will negotiate tight urban spaces. Would we have figured out a better way to get around by then? Would we have bold modes of transportation?

Several ideas focused on new wheeled gadgets, while others looked at revamping city infrastructure altogether, but 2030 won’t necessarily have the flashiest elements, Adamson says.

“It’s going to be much the same as it is today. How you get around will depend on where you’re born, the kind of society you live in, the kind of infrastructure you have.”

“The nature of the fuels, maybe that will change some of the mobility, but I don’t see by 2030 there’s gonna be a wholesale change in how people get around,” she says.

MOVING INTO A NEW MORAL AGE

We are moving into a new moral age, which Adamson says is perhaps one of the most disruptive things. “For centuries, we’ve believed that economic values are human values, and we’ve used those economic values to build a big globalized society. And what we’re beginning to see is that Gen Z, Gen Alpha, and societies worldwide are starting to say that ethics, morals, and culture may be more important to them than economic or financial advancement.”

Well, all that’s good, ethical living could be a dangerous time. What she’s not as optimistic about is our ability to maintain harmony in the world. The comparative peace and stability we’ve enjoyed over the last couple of hundred years have been based on economic agreement, a universal value, says Adamson.

“And if that’s no longer a universal value, it’s quite a dangerous period we’re moving into, as it gives people the opportunity to live in a deglobalized world, which could lead to many conflicts.”

“For businesses, it’s particularly important. Previously you were allowed to be neutral, but we’re expecting businesses now to take a moral and ethical stance.”

Moralshoring is what businesses are being asked to do, and that will cause problems for boards, stakeholders, and leaders.

And in this new moral age that we’re moving into now, Adamson says, “ESG is a window into the future,” as it shows what stakeholders worldwide are developing and the different expectations. “But the problem is they’re not developing them uniformly.”

Meanwhile, the loss of privacy is becoming difficult, and we haven’t figured out how to deal with that — how much data we provide and where it goes, and the trade-off being we don’t have to wait in long lines at the supermarket, or getting personalized services at the airport, for example. But most people were simply never given a choice to accept the trade-off.

Talking about the data economy, Adamson says businesses are “weaponizing our data against us to get us to buy stuff.”

She adds that the existing technology infrastructure could be used much better, and the incentives around developing that technology must change.

“AI can be extremely useful, but it’s not very good as a general-purpose technology because the world is not a narrow use case. When it comes to uncertain environments, the priority isn’t to predict, which is what AI is doing. The priority is to adapt, and that’s what humans do.”

TECHNOLOGY CAN’T FIX CLIMATE CHANGE

If we are to guess the future, there is another one that we need to acknowledge: the climate. For Adamson, the choices around whether we have a livable or dystopian future aren’t necessarily the technology.

“Technology cannot fix climate change. Only people can fix it; we need to recalibrate what we value. For centuries, we have chosen to measure and be concerned and report certain things, not others… So we need a wholesale recalibration, and then technology comes into its own. We will need massive collaborative ecosystems and data infrastructure to measure new things we’re beginning to understand that we value.”

Technology is not going to solve climate change, but it’s an important part of recalibrating values at the workplace, which future skills will be essential. “I talk about leadership, and it’s always used to be about command and control and hierarchies. Now, we’re seeing a shift.”

“Leaders must move from command and control to more empathy, 360-degree thinking, and cultural competence.”

Whatever the circumstances we have inherited, change is possible. Focusing on big and solvable problems can make a difference – a new set of tools can help build a better future. So how readily can organizations be?

Businesses need to identify the big-ticket items that will impact the future most. In a nutshell, she says that companies must look at sustainable transformation.

“It’s becoming a cultural and a commercial imperative, and there are four main competencies around that: ESG, data and digital, enterprise and supply chain agility, and finally, purpose-led business. Expect more and more to be heard about purpose-led business, your North Star, because in this new moral age with moral assuring going on, that North Star is going to be absolutely essential.”

It’s tempting, particularly at this moment, to bask in a positive outlook on the future. A dose of faith in human progress is hard to resist. But the future goes beyond intuition, even beyond theory. “You probably don’t expect a futurist to tell you this, but no one can predict the future. But you can be wise to the future,” Adamson contends.