- | 1:00 pm

How VCs are vying for a piece of your brain—literally

To pay for futuristic brain implants, companies are eyeing a surprising business model: Medicare reimbursements.

An influx of funding for futuristic brain implant startups shows that the path forward for the technology, at least for now, doesn’t involve hooking everyone up to a computer. Rather, venture capital firms are throwing tens of millions of dollars into extremely expensive medical devices that will help people with specific health conditions—and almost certainly need to be covered by insurance.

Of course, the idea of brain implants isn’t new. Movies like The Happiness Cage and Johnny Mnemonic have explored what a world full of partial cyborgs might look like. Researchers have spent decades studying how to safely install electronics into the human body, and have already demonstrated that brain implants can be used to move robotic arms and speak through a computer.

The technology still isn’t common, though. Today, it’s reported that fewer than 40 people have received Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI) that connect their minds to machines. The available implants are almost entirely experimental, and they’re generally not for sale. There are also plenty of concerns about brain implants, from the potential risk of infection to questions surrounding their cybersecurity and privacy protections. Recent polling shows that the general public isn’t enthusiastic about the idea of using brain implants to improve cognitive abilities, either.

But that could soon change, thanks to a new crop of companies racing to bring brain implants into the mainstream. Startups like Precision Neuroscience and Synchron—along with Elon Musk’s brain-machine interface venture, Neuralink—are developing technology that could help people with conditions like quadriplegia, traumatic brain injury, and stroke. At the same time, these startups aim to compete in the lucrative medical devices industry by convincing private insurers, along with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, to pick up the cost of their products for patients. Executives might even charge for periodic software updates to the implants.

“If we’re able to achieve our mission, I think it will be very hard to argue against providing a reasonable rate of reimbursement for this technology,” says Michael Mager, CEO and cofounder of Precision Neuroscience, a brain implant startup that was founded two years ago. “I fully anticipate it will be a fight. But I think it’s a fight that companies like ours ultimately will win.”

Venture capital firms are spending tens of millions in the hope that Mager is right. Last month, Precision raised $41 million in a series B funding round led by Forepont Capital Partners, bringing the company’s total fundraising haul to $53 million. All that investment is predicated on the idea that Precision’s tech—a tape-like microelectrode that reads electrical signals from above the brain—could eventually help several million people in the US with different forms of motor paralysis. But development is still in early stages. While the company has tested a prototype implant in pigs, it has yet to send its first submission to the FDA or try the tech in a human. It’s hoping to achieve both of those milestones later this year.

Precision isn’t alone. Synchron, a neuroscience startup developing a stent-like device that is inserted via the brain’s blood vessels, raised $75 million late last year, and both Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos are backers. The company has raised $145 million since it was founded in 2012 and published the results of a study looking at its device’s safety for humans just last month.

There’s also Neuralink, which raised more than $200 million two years ago. The company is notorious for its flashy live demonstrations featuring chip-implanted pigs and monkeys and hopes to implant its device in a human for the first time sometime this year. (There a couple caveats: Some of the milestones that Neuralink’s reached have already been reached by academic researchers, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture is also investigating whether the company’s animal trials have violated the Animal Welfare Act.) New funding for brain implant startups is part of a broader surge in support for neuroscience tech. Cajal Neuroscience, a drug discovery startup focused on neurogenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, raised $96 million last fall. And a company called Alto Neuroscience has raised $100 million since 2019 for its technology, which involves using artificial intelligence to develop and tailor psychiatric medications.

“It’s really started to pick up in the past three to five years,” Carol Suh, a partner at ARCH Venture Partners, which has funded several neuroscience companies, told Fast Company. “We’re really at a convergence of high unmet need, advancements of understanding biology, as well as the progression of new tools and technologies.”

But there are also concerns. The research process—and the race to get a brain implant device to market as quickly as possible—has created ethical problems. While medical research often involves animal testing, Neuralink has been accused of rushing through its trials, and, as a result, killing more animals than necessary. Human trials will create other challenges, and could become real headaches for future patients. Some devices may fail, for instance, leaving people with obsolete technology in their brains and the difficult decision of whether to try and remove it.

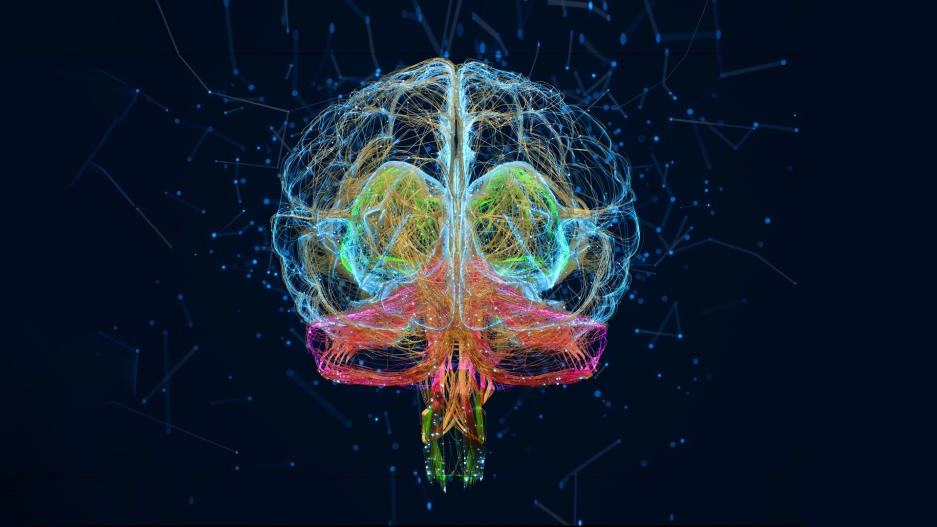

Most brain implant tech starts with the same, basic premise: Neurons, or brain cells, produce electrical signals, which can loosely correlate with a particular thought or action, like moving your hand. Brain implants pick up on these signals, and then communicate with another device—like a robotic limb—or send new electrical signals back into the brain.

Still, the companies working on this tech are also trying to differentiate themselves in part so they don’t have to compete for future customers.

A startup called Paradromics, for example, has focused in part on using better materials that will help its implant to survive in the brain for much longer, while also increasing the number of electrodes, or channels, that the device can support. The company is targeting a somewhat small population: the 150,000 people in the U.S. who they estimate may need an assistive device to speak. Synchron’s technology, meanwhile, is designed to be inserted through the jugular vein, so it doesn’t require open brain surgery—this could make things easier for doctors and less intensive for patients. Similarly, Precision Neuroscience’s implant is designed to sit on top—but not be inserted directly into—the brain. This is supposed to appeal to people who may not want a more invasive and potentially riskier implant.

While brain implants could be extremely helpful, they’re also bound to be extremely expensive. Matt Angle, the CEO and founder of Paradromics, estimates that his company’s implant would require insurance reimbursement of around $150,000. And that’s just for the actual device. Any necessary surgery to implant or remove the technology would be an additional cost, startup executives told Fast Company. There’s another twist: companies are designing their devices to work with software that will, from time to time, need to be updated, and likely, for a fee.

“There is some consensus across the field that being able to move to a kind of SAS [software as a service] model would be beneficial for the whole field,” says Angle. “It’s helpful on the company side. It makes the revenues a little bit more predictable. It’s helpful on the payer side. It kind of distributes the cost over a long time. It’s helpful on the patient side as well. It encourages companies to stay engaged. “

The high cost explains why so many of these companies aren’t planning for a future in the consumer technology sector, or expecting their implants to become the next iPhone anytime soon. Instead, they’re preparing for a long-term business model of insurance reimbursement. Synchron has already had some preliminary discussions with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and executives pointed out that much of their target patient populations lean older and are very likely to use Medicare.

Of course, this is all assuming that these companies manage to get through the Food and Drug Administration first. None of these startups currently have a commercially available product, and executives say it could be years before one of their devices pass safety and efficacy trials. In the meantime, the business of brain implants is still a risky bet.