- | 9:00 am

Neuroscience explains how diverse leaders pay an invisible ‘mental tax’

Zora’s House founder says these leaders are navigating not only the demands of their work and leadership but also feel pressure to mitigate the stereotypes and misconceptions that their peers may have about their identity.

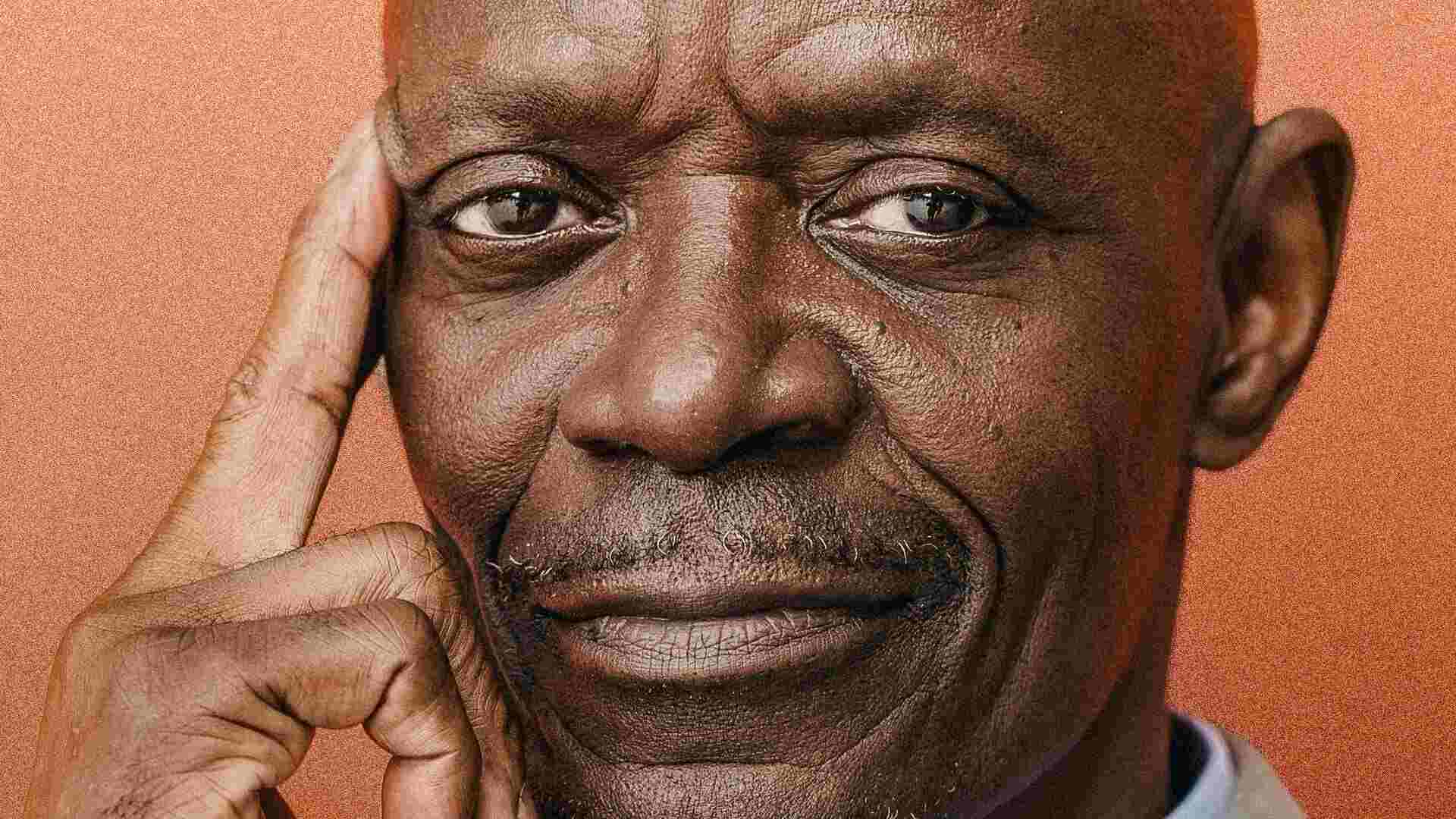

“You’re nothing like your predecessor,” one of my white colleagues said, chuckling. “She was an angry Black woman.”

It was my first week on the job. As one of the two Black people on an otherwise completely white leadership team, these were not the first or the last problematic comments I would hear spoken by both colleagues and superiors throughout my tenure as a newly minted director.

While I was constantly praised as a high performer, I knew the work environment was taking a toll—I just never knew how much of one.

It turns out, that there is a real cost associated with diverse leaders who must constantly navigate their status as the first, the only, or the other. These leaders are navigating not only the demands of their work and leadership but also feel pressure to mitigate the stereotypes and misconceptions that their peers may have about their identity.

A study published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience highlights three key parts of the brain that are taxed when leaders from non-white groups interact with their peers: the anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain that helps us to regulate our emotions and make decisions; the rostral prefrontal cortex, the part of our brain that processes sensory information and helps us with retaining memory; and the retrosplenial cortex is part of our brain that allows us to tap into our imagination and plan for and envision a different future.

The research reveals that the more deeply someone is engaged in creating an impression or managing somebody else’s perception of them, the more intense the connectivity between these three different regions of our brain.

In other words, when diverse leaders are engaged in that day-to-day work of navigating their otherness, when they are involved in the day-to-day mental labor of figuring out “how am I being perceived in this space” as the only woman, the only Black person, the only differently-abled person, they are using incredibly important parts of their brain to do so.

SOCIETY’S INVISIBLE BRAIN DRAIN

While this mental tax affects diverse leaders across the board, the population we need to pay the closest attention to is women of color.

Women of color will be the majority of women in the United States by 2060, and they are the most ambitious by far: women of color are 5% to 7% more likely to complete college than men of color. Meanwhile, Black women are starting new businesses faster than any other group. Moreover, on the career front, 83% of Asian women, 80% of Black women, and 76% of Latinas say they want to be promoted, compared to 75% of men and 68% of white women.

Yet, women of color leaders are particularly hard hit by the mental tax of navigating others’ perceptions. The need to navigate the intersection of both their racial and gender identities means that the fastest-growing and most ambitious population in our country is spending way too much of their brain power mitigating bias and microaggressions, and not enough of it leading, creating, and envisioning a brighter future for us all.

THIRD PLACES AREN’T SOLUTIONS

“Third places” were supposed to be one way to address this problem.

Popularized by sociologist Robert Oldenburg, “third places” are informal, public spaces that anchor individuals and communities. Oldenberg calls one’s “first place” the home and the people the person lives with. The “second place” is the workplace—where people may spend most of their time.

From neighborhood coffee shops to libraries and corner stores, “third places” are where people go to unwind, connect, and reconnect with the people in their lives, to talk about and process the things that matter to them. By definition, “third places” are meant to serve as incredibly critical community spaces outside of work, but can still serve as incubators and catalysts for art, creation, innovation, and leadership.

The problem is that many traditional “third places” still lack diversity, comfort, and even safety for women of color to engage and contribute fully.

WE NEED MORE “FOURTH PLACES”

To stem this invisible brain drain, communities need to create intentional spaces for women of color and other marginalized people to come together, connect, and create where they feel safe and where they aren’t forced to use valuable mental energy to navigate their otherness. I call these “fourth spaces.”

Fourth places are community gathering spaces where the identities and ideas of a particularly marginalized group are centered. For example, my organization, Zora’s House, is a coworking space and leadership incubator created by and for women of color.

While traditional offices are closing due to lack of occupancy, Zora’s House has raised $5.3M in the last year to expand into a new 10,000 multifunctional community space. And we’re not the only ones. Across the country, coworking spaces and social clubs inspired by, and catering to, women of color are thriving.

Our world and the problems we face get more complex every day. Transforming our future requires the brightest minds at the table, operating at full capacity. Fourth spaces alone will not transform the structural inequity many women of color leaders face every day but are an essential step in the right direction.