- | 11:00 am

Meet the architect designing for neurodiversity

Bryony Roberts devotes much of her practice to designing inclusive spaces that support everyone.

For three days in September, an unusual urban furniture collection took over New York City’s famous Josie Robertson Plaza outside Lincoln Center. Dozens of soft cushions radiated around the central fountain. Some people pushed them together to form one giant beanbag, while others dragged them to a quieter edge of the plaza. “People of all ages started making their own living rooms,” says Bryony Roberts, the founder of Bryony Roberts Studio and the designer behind the installation called “Softy.”

The installation was part of the Big Umbrella Festival, an annual event that organizes free activities for young people with autism and other developmental disabilities and their families. (Other installations included an alphabet-themed playground made up of individual letter-shaped toys, and a room filled with pneumatic musical instruments that could be played by sitting, lying, or rolling on inflatable pillows connected to them). “Softy” only lasted a few days, but for Roberts, it showed how public space can be activated, fluid, and above all, inclusive.

Over the past few years, Roberts has devoted much of her practice to designing such spaces, with a particular focus on neurodiverse people—a term used to describe developmental disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, and Dyslexia. The World Health Organization estimates that one in eight people in the world is neurodiverse, but considering that many of these conditions are hard to diagnose, the number is likely higher.

Despite how common neurodiversity is, few public spaces are shaped to account for the different ways people think, communicate, or interact with the built environment. Part of the problem is that there are no set guidelines about how to design for neurodiversity. That’s why Roberts—who’s also taught a course about sensory public spaces at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation—is now working on a project called “Neurodiverse City.” Developed in collaboration with Verona Carpenter Architects and WIP Collaborative, a feminist collective made up of independent design professionals (including Roberts), the concept was one of two winning projects of the Design Trust for Public Space’s Restorative City competition.

“Neurodiverse City” advocates for inclusive public spaces that support everyone, regardless of their physical, neurological, or emotional state. The project is still in its early phases while the Design Trust raises funds, but once that happens, the team will begin by examining existing public spaces in the city, including playgrounds, pocket parks, and streetscapes. By 2024, Roberts expects they will have gathered enough insights to be able to develop design guidelines and policy recommendations. At that point, they will form an advisory committee and start coordinating with city agencies in order to implement those policies in both new and existing public spaces.

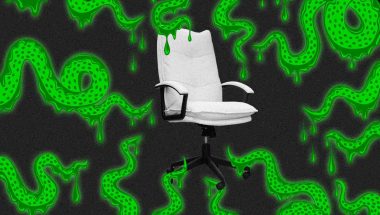

In the meantime, Roberts is focusing on small yet equally transformative interventions, each of them designed in concert with self advocates, occupational therapists, and organizations, such as the Marcus Autism Center and Parent to Parent. Last year in Atlanta, she designed “Outside The Lines,” a sinuous installation with multicolored ribbons rustling in the wind, and seating made of webbed netting. A week later, in Manhattan, she opened Restorative Ground, an all-ages playground designed with WIP Collaborative that featured distinct zones for reading, playing, and resting. And just this year, she unveiled Softy at Lincoln Center.

Each project was designed with neurodiverse populations in mind, but all of them look different. This strategy reflects a simple truth, namely that the experience of someone on the spectrum can’t be generalized. “If you’ve met one autistic person then you’ve met one autistic person,” says Roberts.

Still, a few common denominators connect the projects. Roberts says that, broadly speaking, textures and visual patterns can be calming for people with autism and other developmental disabilities. “Being able to interact with something, to move something, to run your fingers on it can be helpful for people in the process of self soothing,” she says. At the same time, too much stimulation can be debilitating for some people, “so it becomes important to create choice,” she says. At Restorative Ground, for example, each zone is defined by its own material: artificial turf provides a “grippy” texture that people can lean against or climb, while netted hammocks support people lounging. This particular project was informed by a dozen interviews with experts and advocates on neurodiversity, including organizations like the Global Autism Project.

Crucially, the design principles Roberts is advocating for—sensory stimulations, or the ability to choose where and how you want to sit in a public space—also apply to neurotypical people. “So many people are not comfortable in typical public spaces and need a greater range of options,” she says.

For Roberts, “it’s about designing for everyone,” and a great place to start doing that is in public spaces where it’s easier to foster tolerance and understanding across cultural divides. Public spaces can bring people together by breaking down social divides, “but if you don’t have anything there to invite activity or even just hanging out, then there’s nothing to start to build those connections,” she says. “If we can find a way to design for bodies that celebrate the full range of sensory, emotional, psychological experiences, and also cultural experiences, that’s how we get to more inclusive public spaces.”